‘The world cannot be governed without juggling.’

- John Selden, English Jurist (1584-1654)

Below analysis from AICD Chief Economist Mark Thirlwell. For governance headlines click here.

In recent pieces on the balancing act currently required of Australia’s policymakers, I’ve drawn on the metaphor of a tightrope walker seeking to traverse a narrow course between inflation risk on the one side and recession risk on the other. But when Treasurer Jim Chalmers presented his third budget tonight, the image that came to mind was not an economic version of funambulism but instead a kind of macro-political juggling act, as Budget 2024-25 worked hard at keeping multiple balls aloft.

Thus, there was a ball representing the budget strategy of fiscal repair and debt stabilisation; another capturing the social, economic and political imperatives around the delivery of cost-of-living relief to a swathe of squeezed Australian households; one to stand in for the constraints imposed by the RBA’s ongoing fight to return inflation to target; another to signify the requirement to boost productivity growth and the economy’s medium-term growth prospects; and of course the shiny new ball that is the Government’s take on the global shift to Industrial Policy in the form of the Future Made in Australia project. Of course, there were even more than this short list, but that’s more than enough juggling to be going on with.

So, how did the budget’s juggling act go? After all, Budget 2024-25 had set itself a tough task: Respond to the complex nature of Australia’s macroeconomic environment with its mix of inflationary pressures and growth fragilities while simultaneously addressing political pain points, structural constraints, and delivering on some ambitious medium-term plans. Achieving success across all these areas – keeping all those balls in the air – was always going to be difficult, not least since several of the objectives would ordinarily tend to push policy in different directions.

Given that context, and given the constraints implied by those multiple objectives, Budget 2024-25 represents a fairly decent juggling act, albeit one that perhaps sometimes comes at the cost of some loss of focus relative to a more targeted fiscal policy approach. It also remains hostage to its projections for a relatively benign economic environment despite the presence of a plethora of downside risks. And importantly, it includes some key judgment calls – including increased spending commitments leading to increased deficits in 2024-25 and again in 2025-26 that will be delivered at a time when the outlook for inflation remains ambiguous – that looks set to be stress tested as we move deeper into the next financial year.

Attempting to reconcile inflation reduction and cost-of-living relief

As promised pre-budget, there is additional cost-of-living support for households. The centrepiece of the fiscal response here comes in the form of the already-announced adjustments to the Stage 3 tax cuts, which were reworked to deliver more support to taxpayers on middle and lower incomes at the cost of less largesse to higher income taxpayers. In addition, Budget 2024-25 delivers an extension and expansion of Energy Bill relief and Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Economic purists will quite reasonably fret about the implications of these latter measures for spending and therefore underlying inflationary pressures in the economy. But the Government will point to the Budget Papers’ estimates that suggest that together they will take perhaps half a percentage point off the headline rate of inflation and thereby push it nearer to the top of the target band by the end of this year. Granted, the impact on underlying inflation is likely to be more ambiguous, although the Budget Papers reckon that the changes ‘are not expected to add to broader inflationary pressures in the economy.’

Sticking with the theme of providing relief to households (voters), there are additional measures to help with cost of living (cheaper medicines) and to strengthen the social safety net (adjustments to JobKeeper eligibility and an extended freeze on social security deeming rates).

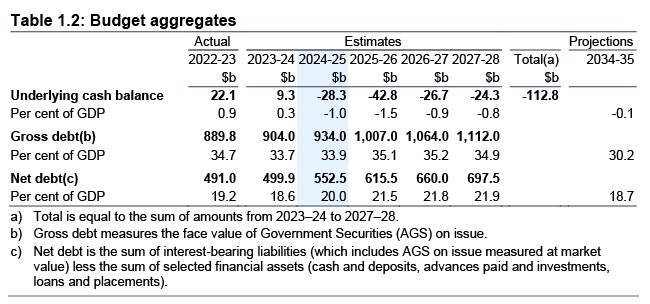

Relative fiscal restraint and a second budget surplus for this financial year

The budget story got off to a positive start with the announcement of a second consecutive budget surplus – the first in almost two decades. The Treasurer announced that the underlying cash balance in 2023-24 would be a surplus of $9.3 billion or about 0.3 per cent of GDP. That’s a marked improvement relative to the narrow $1.1 billion deficit projected at the time of last December’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO). It also marks the first time an Australian federal government has been able to deliver back-to-back surpluses since the period between 2002-03 and 2007-08, before the onset of the global financial crisis. The Budget papers highlight that this second surplus was accomplished by the Government returning 96 per cent of tax receipt upgrades (excluding the GST) to the budget. They also note that real payments growth over the forward estimates will be limited to an annual rate of 1.4 per cent, which is below the 3.2 per cent average recorded over the past 30 years. Modest underlying cash deficits of less than one per cent of GDP are then projected over the medium term, with the underlying cash balance recording a deficit of just 0.1 per cent of GDP by 2034-35.

Note, however, that this is the only expected surplus over the budget forward estimates to 2027-28. Next year, the underlying cash balance is forecast to swing into a deficit of $28.3 billion or about one per cent of GDP as additional policy decisions – mainly on the spending side – taken since December’s MYEFO have led to a deterioration in the underlying cash balance of around $9.5 billion. It is a similar story in 2025-26 when new policy decisions contribute to a further deterioration in the fiscal balance of around $10.3 billion (see annex note, below). This translates into a forecast for the deficit to widen further to $42.8 billion or 1.5 per cent of GDP in 2025-26. Given that there is a significant probability that Australia will still be trying to manage an inflation problem over at least part of this period, that extra injection of spending does represent a clear macro risk.

Still, the deficit is then expected to narrow to less than one per cent of GDP over the final two years of estimates.

Delivering on debt stabilisation

That forecast sequence of budget deficits means that after falling to 33.9 per cent of GDP this year, gross debt as a share of the economy then rises to a peak of 35.2 per cent of GDP in 2026-27. However, it then starts to fall again, declining to a projected 30.2 per cent of GDP by June 2035. As a result, gross debt as a share of GDP is now expected to peak one year earlier and 0.2 percentage points lower than in the corresponding MYEFO projections, and to be lower across the entire projection period overall. That modestly improved debt profile helps the budget to deliver on its debt sustainability objective. Note, however, that net debt is expected to be higher than the MYEFO estimates across each year of the forward estimates.

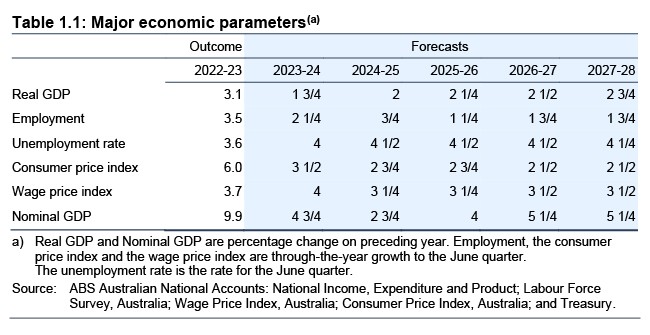

A fairly optimistic take on the economic outlook

The optimistic take on the budget’s impact on inflation plus the support for embattled households is both underpinned by and helps Budget 2024-25 deliver a reasonably positive set of economic forecasts. While acknowledging the presence of ‘substantial risks’ to the domestic economic outlook together with the possibility of adverse external shocks, the budget projections set out a future in which higher wages growth, moderating inflation, continuing employment growth, and the cost-of-living tax cuts all support household consumption. They also assume that recent strength in business investment, net exports and public investment will be sustained.

As a result, the Budget Papers reckon that, after expanding by a relatively soft 1.75 per cent in 2023-24, real economic activity will pick up a little in 2024-25 with growth accelerating to two per cent and then rising again to 2.25 per cent in 2025-26. The increase in activity is then projected to continue over the forward estimates, rising to 2.75 per cent by 2027-28. (By way of comparison, the latest RBA forecasts see real GDP growth at 1.7 per cent in 2024-25 and 2.3 per cent in 2025-26.) The Budget projections do see the unemployment rate climbing to 4.5 per cent next year, but this is assumed to be the peak.

And not forgetting those other spending commitments

And of course, there’s more. Budget 2024-25 also offers additional support for home building and social housing; it delivers the promised student debt relief and the promised superannuation on government-funded paid parental leave; and it produces more spending on defence, with the Budget Papers noting that the Government will be investing an additional $50.3 billion over the next decade through the 2024 National Defence Strategy. Small businesses get a little something too: the $20,000 instant asset write has been extended until 30 June 2025. There is some money for expanded tertiary education. And finally, there is an announced $22.7 billion of investment for the Future Made in Australia program that is to be delivered over the next decade – a down payment on those ambitious plans for industrial policy and a new Australian growth model.

Annex: A note on payments, receipts and parameter variations

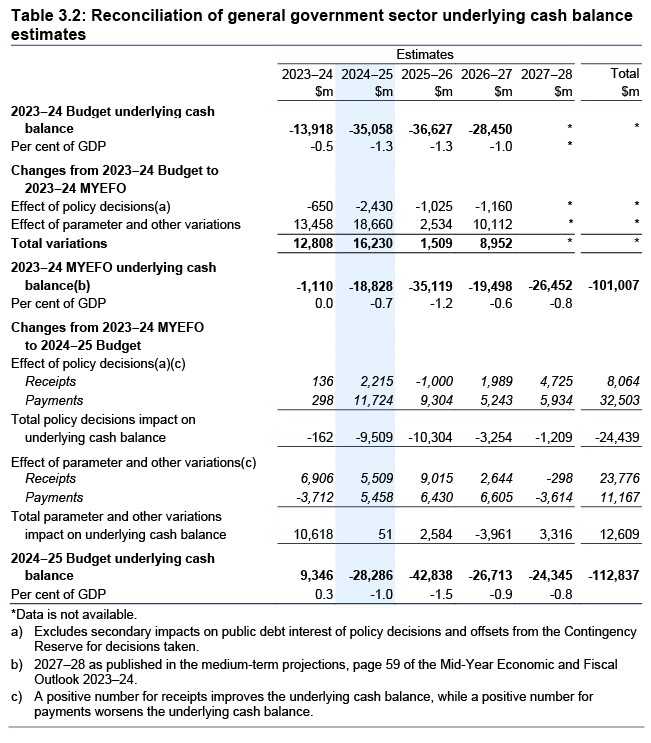

The shift in the fiscal bottom line between the numbers presented in the MYEFO and those presented in Budget 2024-25 represents the combined impact of policy decisions taken by the government with respect to receipts and payments, plus the impact of so-called parameter and other variations on those same receipts and payments.

Relative to the MYEFO, policy decisions have increased total receipts by $2.2 billion in 2024-25 and by $8.1 billion over the five years from 2023-24 to 2027-28. At the same time, parameter variations have increased total receipts since the MYEFO by $5.5 billion in 2024-25 and by $23.8 billion over the five years to 2027-28.

Meanwhile, new policy decisions taken since the MYEFO have increased total payments by $11.7 billion in 2024-25 and by $32.5 billion over the five years to 2027-28. Parameter and other variations have further increased payments by $5.5 billion in 2024-25 and by $11.2 billion over the five years to 2027-28.

Overall, that means combined policy decisions have worsened the underlying cash balance in each year of the forward estimates, ranging from a $9.5 billion hit to the bottom line in 2024-25 and a $10.3 billion deterioration in 2025-26 to more modest falls of $3.3 billion and $1.2 billion in the 2026-27 and 2027-28, respectively.

You can access the full 2024-25 Budget paper here.

Governance Policy Headlines – Head of Policy Snapshot

Christian Gergis, Head of Policy

Although there were no major surprises, tonight’s budget highlighted key elements of the government’s policy agenda including greenwashing enforcement, AI regulation and investment in the net zero transition.

Sustainable finance agenda and greenwashing funding for ASIC

The Government will provide $17.3m over four years from July (and $3.1m per year ongoing) to promote the development of sustainable finance markets in Australia. See AICD article on the sustainable finance strategy here.

Funding includes: $10m over four years from 2024–25 (and $1.9m per year ongoing) for additional resourcing for ASIC to investigate and take enforcement action against market participants engaging in greenwashing and other sustainability-related financial misconduct.

Although not explicit, it is assumed this enforcement budget will at least partially be allocated to the regulator’s enforcement of the planned mandatory climate reporting regime expected to commence from January 2025 (see director’s guide here).

As part of its broader net zero agenda, see below, the Government has allocated $1.3m over four years for Treasury to develop and publish high-quality guidance on best practices for Australian businesses when developing net zero transition plans.

Such transition plans, although not explicitly required under the forthcoming mandatory climate reporting regime, are increasingly expected by investors and remain a contested area.

There will also be $5.3m over four years for Treasury, ASIC and APRA to deliver the sustainable finance framework, including issuing green bonds, improving data and engaging in the development of international regulatory regimes related to sustainable finance.

AI regulation to support safe and responsible use

The Government will provide almost $40m over five years from 2023–24 for the development of policies and capability to support the adoption and use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in a safe and responsible manner.

Key measures include $21.6m over four years to establish a reshaped National AI Centre (NAIC) and an AI advisory body; $15.7m over two years to support industry analytical capability and coordination of AI policy development, regulation and engagement activities across government, including to review and strengthen existing regulations in the areas of health care, consumer and copyright law; and $2.6m over three years to respond to and mitigate against national security risks related to AI.

In parallel, the Parliament is also considering responsible AI regulation through an ongoing Senate select committee process (see here).

Aged Care Governance

The Government will provide $2.2 bn over five years from 2023–24 to deliver key aged care reforms and to continue to implement Royal Commission recommendations (see director’s guide to governing for quality care here).

Funding includes: $1.2 bn over five years from 2023–24 for enhanced aged care digital systems; $531.4m in 2024–25 to release 24,100 additional home care packages in 2024–25; and $11.8m over three years from 2023–24 to implement the new Aged Care Act, including governance activities and program management.

Governance reforms include the contentious proposal for a new responsible person duty which the AICD and other industry stakeholders remain concerned about (see here).

Net zero transition and supporting renewable energy

With aspirations of making Australia a “renewable energy superpower”, the Government will provide an estimated $19.7bn over ten years from 2024–25 to accelerate investment in Future Made in Australia priority industries, including renewable hydrogen, green metals, low carbon liquid fuels, refining and processing of critical minerals and manufacturing of clean energy technologies including in solar and battery supply chains. Funding is intended to catalyse clean energy supply chains and support Australia to become a renewable energy superpower.

Funding includes an estimated $7.1bn over 11 years from 2023–24 (and an average of $1.5 billion per year from 2034–35 to 2040–41) to support refining and processing of critical minerals; an estimated $8bn over ten years from 2024–25 (and an average of $1.2 billion per year from 2034–35 to 2040–41) to support the production of renewable hydrogen; and $1.7bn over ten years for the Future Made in Australia Innovation Fund.

The Government’s net zero agenda includes almost $400m over five years from 2023–24 (and an additional $616.8m from 2028–29 to 2034–35 and $93.4m per year ongoing) in additional resourcing for the Net Zero Economy Authority, and other agencies to promote decarbonisation. This will include $209m over four years to coordinate policy and deliver across government, broker investments that create jobs in regions, and support workers affected by the transition.

The Government will also provide $182.7m over eight years from 2023–24 to strengthen approval processes to support the delivery of the Government’s Future Made in Australia agenda, including $96.6m over four years to strengthen environmental approvals for renewable energy, transmission, and critical minerals projects, deliver additional regional plans, and improve the environmental data used in decision-making; $20.7m over seven years to improve community engagement and social licence outcomes, and the development of a regulatory reform package to realise community benefits in regional communities affected by the energy transition.

Almost $20m has been allocated over four years to develop a national priority list of renewable energy related projects and process assessments.

Climate change and the skills challenge

The Government will provide $218.4m over eight years to support a Future Made in Australia through the development of a skilled and diverse workforce and trade partnerships.

Funding includes: $91m over five years from 2023–24 to support the development of the clean energy workforce, including through addressing vocational education and workforce shortages; and $55.6m over four years to establish the Building Women’s Careers program to drive structural and systemic change in work and training environments.

Nature and biodiversity

The Government will provide a further $40.9m over two years from 2024–25 to continue implementing the Nature Positive Plan.

Building on last year’s budget, additional funding includes: $17.6m over two years to establish and commence operation of the Nature Repair Market; $14m over two years for the Clean Energy Regulator to administer the Nature Repair Market; $5.3m in additional funding to progress legislative reforms; and $4.1 million over two years to drive voluntary uptake of the Nature Repair Market and nature-related reporting by businesses.

It will be interesting to see how the Government’s nature disclosure plans evolve, with mandatory climate reporting seen as the first step towards a broader sustainability reporting framework.

The Australian Government has been a major supporter of the recently finalised Taskforce on Nature Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), and is set to host the global Nature Positive Summit in October, indicating this is an area of increasing policy focus (see director’s resource to nature as a material risk here).

Competition law reforms and financial services regulatory grid

The Government will provide $13.9m over five years from 2023–24 for competition reforms, including: replacing Australia’s current merger control with a faster, more transparent and streamlined mergers control system; expanding the scope of the Competition Review to include advice on non-compete clauses, and to work with states and territories to revitalise National Competition Policy; and developing a Regulatory Initiatives Grid for the financial sector to provide greater transparency of announced regulatory reforms and planned regulator initiatives to promote better engagement with industry and reduce regulatory burden.

The AICD, along with other peak bodies, has been a supporter of the Regulatory Initiatives Grid and would like to see such a measure applied more broadly to encourage better coordination and phasing of regulation.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content