Property markets have been the centre of attention this week. Mostly this was due to developments around troubled Chinese property developer Evergrande. We (again) spend some time discussing this in the latest Dismal Science podcast, where we dig into the proposition whether this could become a ‘Lehman moment’ for China. Our conclusion is, probably not. But that’s far from saying the risks here are negligible.

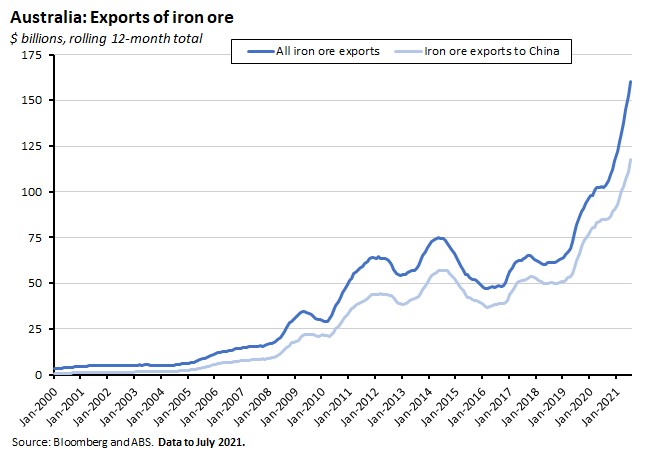

Closer to home, there are potential implications for the iron ore price – which has now fallen by more than half from the record high set in May this year – and therefore for Australia’s trade and budget outcomes. Meanwhile, new ABS data showed that the record increase in residential housing prices in the June quarter we reported on last week has helped drive the largest quarterly gain in wealth seen since the peak of Australia’s recovery from the GFC, pushing total household wealth and wealth per capita up to record highs in Q2. Also on the housing market, the RBA has been communicating its views on housing affordability (in the form of a submission to a House of Representatives inquiry) as well as on the implications of current trends for financial stability. This week’s readings include an overview of the central bank’s analysis, including flagging the rising chances of a future macro-prudential policy intervention.

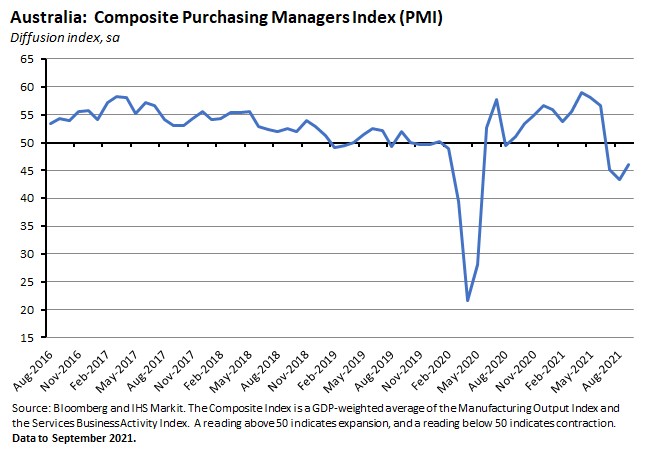

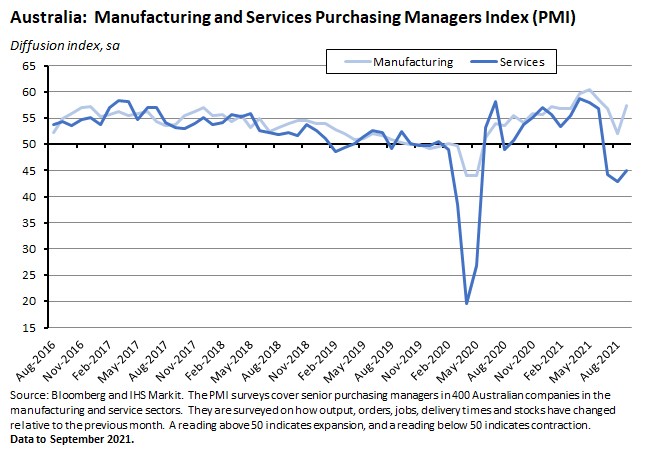

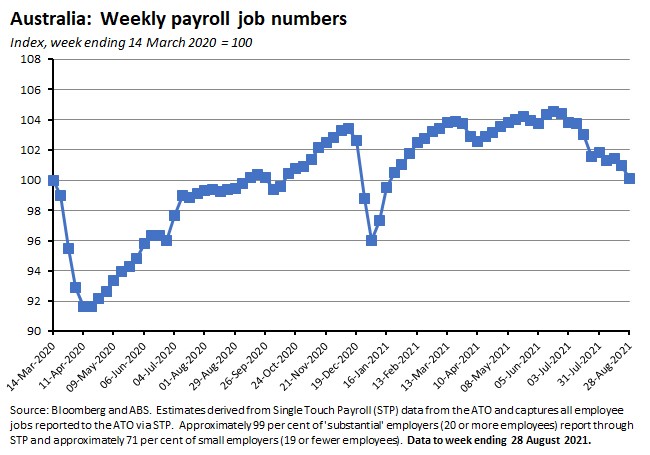

On the data front, the flash Composite PMI for September showed business activity contracting for a third consecutive month as lockdowns continue to take a toll. That said, the pace of decline slowed this month as the Composite, Services and Manufacturing PMIs all lifted to three-month highs. Combine that with a recovery in the employment index and a reported improvement in business sentiment and there’s even a chance that September’s result could indicate the start of a turning point for activity. That would be consistent with the position presented in the minutes from the RBA’s 7 September meeting, which reiterated Martin Place’s view that Delta will delay but not derail Australia’s economic recovery. Meanwhile, the variant’s toll on the economy was visible in yet another drop in payroll job numbers, which were down 1.3 per cent over the fortnight to 28 August 2021.

As well as a selection of material on the Evergrande story and the RBA on the housing market, this week’s roundup of reading and listening includes: a Parliamentary Budget Office assessment of Australia’s medium-term fiscal outlook; ABS data on tourism jobs; the latest BIS quarterly review, including an essay on monetary policy and inflation dynamics; Roubini on Stagflation risk; Economics in an Exponential Age; the end of the World Bank’s Doing Business report; is the global housing market broken; fossils as a hot new asset class; do taxes fund government spending; and debating AUKUS.

The Weekly Note and the Dismal Science podcast will both be taking a break next week for the NSW School Holidays, but we will be back the following week.

Finally, stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast . Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The IHS Markit Flash Australia Composite PMI (pdf) rose to an index reading of 46.0 in September up from a (final) reading of 43.3 in August.

Output and new orders (including foreign demand) remained in contractionary territory in September and there was also a further fall in the level of outstanding business. The employment index returned to signalling expansion this month after having turned negative in August. IHS Markit also said that business sentiment overall improved over the month.

Input price inflation rose in September, with firms reporting higher costs across raw materials, transport and wages, and with these costs then being passed on to clients in the form of higher output charge inflation.

The Flash Services Business Activity Index rose from 42.9 in August to 44.9 in September while the Flash Manufacturing PMI rose from 52.0 to 57.3 over the same period.

Why it matters:

With the Composite PMI still below 50, private sector activity contracted for a third consecutive month in September as public health restrictions continue to take a toll on economic conditions. At the same time, however, the pace of decline has slowed, as the Composite, Services and Manufacturing PMIs all lifted to three-month highs following the easing of some public health restrictions. Combine that with a recovery in the employment index, which had dipped briefly into negative territory in August but is now again signalling expansion, add in the reported improvement in business sentiment (with firms hoping that higher vaccination rates will allow further easing of restrictions) and it is possible that September’s result could indicate the start of a turning point for activity. That interpretation is also consistent with some of the discussion in the RBA minutes reviewed below, which noted the RBA’s liaison program had reported that ‘many firms were preparing to look beyond the near-term uncertainty and were committing to previous hiring and investment decisions.’

Also worth noting, however, is that the PMI results continue to signal a combination of significant price pressures and supply constraints.

What happened:

The ABS said that the number of payroll jobs fell 1.3 per cent in the fortnight to 28 August this year, after having fallen 0.4 per cent over the previous fortnight.

Payroll jobs over the most recent two-week period fell 7.1 per cent in the ACT, 2.8 per cent in Victoria and 1.6 per cent in New South Wales. Victoria accounted for more than 54 per cent of the total fall in jobs over the fortnight, followed by New South Wales with a 34 per cent share. The ACT accounted for about nine per cent of national job losses.

Why it matters:

Payroll jobs have now fallen 1.7 per cent since end-July and job numbers are more than four per cent lower than they were in the week ending 26 June 2021. By state, over the past month jobs are down 7.6 per cent in the ACT, 3.2 per cent in Victoria and 2.6 per cent in New South Wales. And over the past two months job numbers have dropped by more than nine per cent in New South Wales, by more than eight per cent in the ACT and by four per cent in Victoria. Movements elsewhere over the same period have been much more muted, however, ranging from a 1.5 per cent drop in Tasmania to a 0.9 per cent increase in Western Australia. That suggests that although restrictions are having a significant labour market impact in directly affected states, any spillovers to other geographies have been relatively limited.

Note that the ABS has changed the format of the payroll jobs releases, which will now combine a shorter interim release with data on Australian and state and territory jobs (like this week’s version) with a more detailed monthly release that will include more detail and also incorporate wage estimates.

What happened:

The RBA published the minutes from the 7 September 2021 Monetary Policy Meeting.

The minutes reported that the ‘outbreak of the Delta variant had interrupted the recovery in a manner that was more severe than expected a month earlier’ and that as a result ‘the near-term outlook resembled the downside scenario presented in the [RBA’s] most recent forecasts.’ As a result, Board members expected that GDP would ‘decline materially’ in the September quarter and that any further improvement in the labour market ‘would be delayed’ with large declines in hours worked and employment expected in both New South Wales and Victoria over coming months.

The minutes then noted that after Q3:

‘…the timing and pace of the rebound in economic activity would depend largely on the lifting of restrictions in response to health outcomes…As vaccination coverage increased, this would allow restrictions to be eased and recovery…to begin in the December quarter. As restrictions were likely to be lifted gradually, the recovery could be slower than experienced earlier in the pandemic, when the end of community transmission of COVID-19 allowed for a more rapid lifting of restrictions. It was possible that precautionary behaviour by households and firms after lengthy lockdowns would also contribute to a slower rebound, although there had been little evidence of this from the international experience or from domestic spending patterns outside of lockdown areas. Information from liaison also suggested that many firms were preparing to look beyond the near-term uncertainty and were committing to previous hiring and investment decisions. In the central scenario, activity was expected to return to its pre-Delta path in the second half of 2022...’

There was also a reiteration of the RBA view that the ‘outbreak of the Delta variant had delayed, but not derailed, the recovery’ even though there remained ‘considerable uncertainty about the timing and pace of the recovery, which was likely to be slower than experienced earlier in 2021.’

The discussion also included a review of the decision to taper the RBA’s bond purchase program, explaining that the central bank had considered two possible modifications to its plans. The first was to maintain the pre-taper rate of purchases at $5 billion a week to at least November 2021 and then review the program, while the second was to taper weekly purchases to $4 billion in line with the plan as originally announced, but in addition to extend the period over which bonds would be purchased at this new, lower rate to mid-February 2022. As we know, the RBA went with option number two earlier this month, with the minutes offering several justifications for this choice:

- With the economy expected to return to its pre-Delta path by mid-2022, the view was that tapering remained appropriate.

- The decision ‘also took account of the fact that a number of other central banks are tapering their bond purchases.’

- And ‘at $4 billion a week, the Bank's bond purchase program is expanding faster relative to the stock of bonds outstanding than that of many other central banks.’

- But the Board also ‘saw value in providing greater clarity regarding bond purchases after November 2021.’

The minutes also discussed developments in the global economy, noting in particular that ‘data on economic activity in China had softened in recent months and the outlook had become more uncertain than it had been for some time,’ partly due to public health restrictions in response to the Delta variant, but also reflecting ‘uncertainty about the effects of a range of recent policy measures, including those aimed at curbing financial stability risks, reducing carbon emissions and achieving broader social objectives.’ The discussion highlighted developments in China’s property and financial markets, noting that ‘regulatory changes aimed at reducing leverage among real estate developers, as well as restrictions on demand for real estate, had led to slower construction activity and liquidity difficulties for some large property developers. This had led to a heightened risk of fire sales of assets and raised concerns about the potential for financial stability issues.’

Finally, this week’s minutes also reported a discussion on the RBA’s arrangements for Exceptional Liquidity Assistance (ELA), noting that it has ‘become increasingly common for central banks to provide more detailed information on ELA arrangements to assist banks in their contingency planning [which] can assist banks in their recovery and resolution planning and thereby support financial stability.’ Under certain circumstances (for example, if liquidity pressures arose in an individual institution), the RBA could provide ELA directly to individual financial institutions. The minutes said that this would be ‘exceptionally rare’, would require the entity in question to have first tested private sources of liquidity, to be solvent, and to provide appropriate collateral. The minutes noted that members ‘endorsed the proposal for the Bank to publish information on its website regarding technical requirements and other considerations for ELA, in order to increase the transparency of ELA arrangements.’

Why it matters:

The minutes added little to the information already provided in the 7 September monetary policy decision and Governor Lowe’s recent speech on Delta, the Economy and Monetary Policy (summarised towards the end of last week’s note). There was a bit more context on the decision to taper the central bank’s quantitative easing (QE) program, with the minutes telling us while the RBA’s chosen approach mainly reflected its optimistic view that the economy would be back on its pre-Delta path by the middle of next year, Martin Place also saw the tapering decisions of other central banks as well as the scale of its bond purchases relative to the pace of government debt issuance as relevant supporting factors. The discussion also flagged China risks and developments, where, as noted below, one consequence for Australia has been a marked fall in the price of iron ore over recent weeks.

What happened:

Since hitting a record high of almost US$235/tonne in May of this year, the price of iron ore has now more than halved. After falling briefly through US$100/tonne earlier this month, at the time of writing the price stood at around US$108/tonne.

The decline in the iron ore price reflects a combination of factors including cuts to Chinese steel production as the authorities target lower carbon emissions and cleaner air, a downturn in the property sector and specific fears around the future of troubled property developer Evergrande and the potential broader implications of any Evergrande default (see this week’s readings below for a roundup on Evergrande).

Why it matters:

The iron ore price is a critical indicator for Australia. In the case of international trade, for example, high prices have helped to deliver record trade and current account surpluses this year. In the year to July, iron ore exports were worth more than $160 billion (or more than a third of total exports of goods and services over the same period) with iron ore exports to China alone worth almost $118 billion.

The iron ore price is also a critical input for the budget. Budget 2021-22 included the conservative assumption that the spot price would decline to US$55/tonne by the end of the March quarter next year, so even after their recent slump, current prices remain some distance above that level. That’s not to say that a smaller drop will not be significant, however: the budget papers (see box 8.2, statement 8, budget paper number one) also estimated that a $10 drop in the iron ore price would lead to a $6.5 billion decline in Australia’s nominal GDP 2021-22 and a $5.7 billion drop in 2022-23, along with a $1.3 billion fall in tax receipts in both of those years.

What happened:

ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence was virtually unchanged (up just 0.2 per cent) over the week to 19 September after having risen 3.1 per cent over the previous week.

In terms of the subindices, ‘current financial conditions’ dropped three per cent and ‘time to buy a major household item’ fell 1.6 per cent, while ‘current economic conditions’ rose 2.2 per cent, ‘future economic conditions’ were up 1.6 per cent, and ‘future financial conditions’ increased 1.9 per cent.

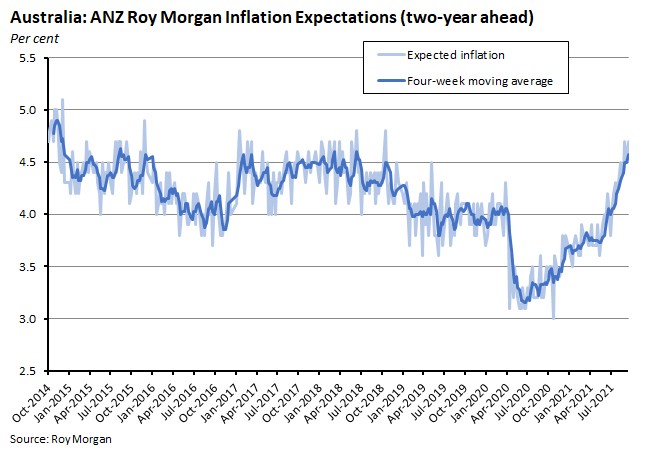

Weekly inflation expectations rose 0.2 percentage points to 4.7 per cent.

Why it matters:

Confidence mainly went sideways last week, as falls in New South Wales (down 4.9 per cent) and Victoria (down 1.1 per cent) were offset by stronger sentiment in Queensland (up 7.3 per cent) and South Australia (up 6.7 per cent).

Meanwhile, inflation expectations are now back to their high of two weeks ago. That also marks their highest reading since October 2018, when the expected inflation rate hit 4.8 per cent.

What happened:

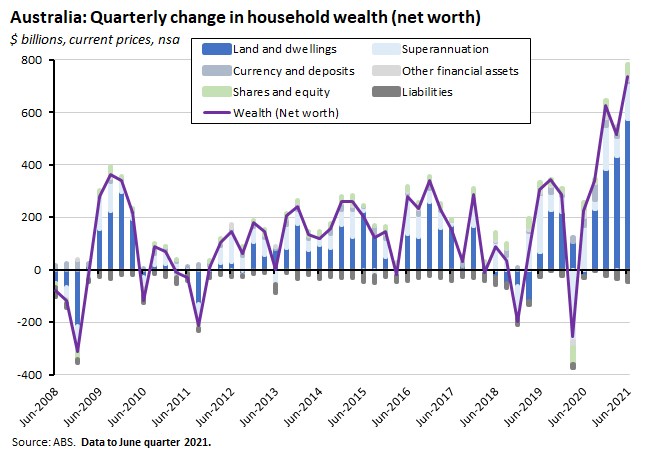

The ABS released the Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth for the June quarter of this year. The Bureau said that household wealth rose by $735 billion (5.8 per cent) over the quarter to $13,433.7 billion while wealth per capita rose to $522,032.

The increase in household wealth reflected a $782.2 billion (6.4 per cent) increase in non-financial assets owned by households and a $206.1 billion (3.3 per cent) increase in financial assets. The former was driven by a $576.5 billion rise in land dwellings powered in turn by rising property prices while the latter was propelled by a $140.8 billion in rise in superannuation balances due to the strong performance of Australian and overseas share markets.

Household liabilities rose $47.2 billion (1.8 per cent) over the quarter driven by a $38 billion increase in housing loans (of which owner-occupiers accounted for $31.9 billion vs $6 billion for investors) and a $8.7 billion rise in unincorporated business loans.

Why it matters:

Both total household wealth and wealth per capita reached record highs in the June quarter. At the same time, the quarterly gain in wealth was the largest seen since the final quarter of 2009 at the peak of the recovery from the GFC. Those results reflect in large part the ongoing impact of housing market developments, which as reported last week saw the strongest growth in the history of the ABS series on residential property prices in the June quarter. Increases in the value of residential property accounted for the lion’s share of the 5.8 per cent quarterly gain in wealth, with a 4.5 percentage point contribution. They were followed in importance by a 1.1 percentage point contribution from superannuation balances.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

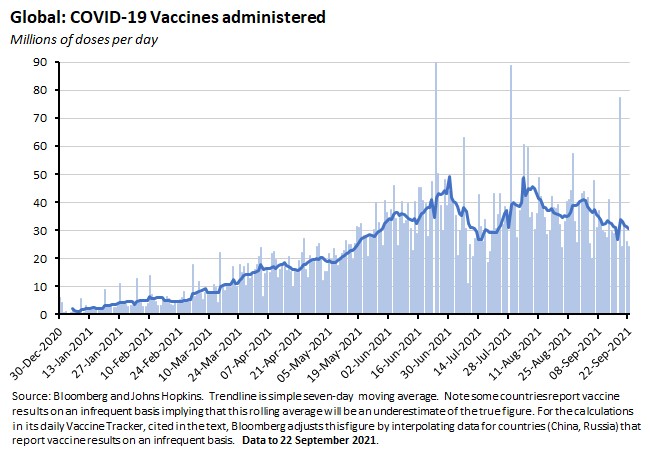

Bloomberg’s COVID-19 vaccine tracker estimates that more than six billion doses of vaccines have now been administered across 184 countries. The average daily rate of vaccination is now running at more than 31.5 million doses. At this pace it would take another six months to cover 75 per cent of the global population.

Bloomberg estimates that those six billion doses are enough to fully vaccinate more than 39 per cent of the global population, but also cautions that the distribution of vaccines remains highly uneven. For example, it estimates that while the world’s least wealthy 52 places account for more than a fifth of the global population they have access to less than four per cent of vaccines.

Why it matters:

As we’ve noted before, the assumption of a successful global vaccine rollout underpins the outlook for the global economy. And the good news is that, broadly speaking, vaccine coverage continues to improve. Back at the end of April we were noting that the world had passed more than one billion doses of vaccines across 172 countries, and at the then average daily rate of 20.3 million doses a day, it would take another 17 months to cover 75 per cent of the world’s population. Now, about five months on, vaccination coverage has increased markedly and the estimated time to vaccinate 75 per cent is down to six months. The not-so-good news is, as noted above, vaccine distribution remains highly uneven, with some of the poorest parts of the world still reporting extremely low vaccination rates. And another not-so-good bit of news is that although the vaccine rate is up on April’s result, it has slowed relative to the last time we reported on the numbers, in late June. Then the average daily rate was running at around 41.7 million doses.

What I’ve been reading . . .

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has released a new report on Australia’s fiscal outlook that provides projections of key budget outcomes over the next decade and that also assesses fiscal sustainability over the next forty years. One headline judgment is that the Commonwealth Government’s fiscal position is projected to improve over the decade ahead, but that the impact of the pandemic on public finances ‘remains profound and uncertain.’ The PBO projects net debt to fall from the budget forecast of a peak of 40.9 per cent of GDP in 2024-25 to reach 37.7 per cent of GDP by 2031-32. That lower debt profile is driven by an anticipated recovery in receipts that leads to declining budget deficits, with the underlying cash deficit projected to fall from 7.8 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 to 1.5 per cent of GDP by 2031-32. A second headline judgment is that ‘the Commonwealth’s fiscal position can remain sustainable over the longer term even if the government continues to run modest deficits.’ Governments ‘will need to act to ensure sustainability’ but over the medium term, gross debt is projected to fall steadily to early 2060s under all but the PBO’s ‘most unlikely worst scenarios.’

RBA Assistant Governor Michele Bullock gave a speech on the Housing Market and Financial Stability. Bullock noted that low interest rates and government support for the housing sector including the HomeBuilder scheme have helped push growth in housing credit up to an annualised pace of around seven per cent, with the RBA expecting that it could climb further to a peak of around 11 per cent by early next year. Moreover, this increase in credit ahead of income growth is occurring at a time when Australian household debt is already high, which Bullock warned could lead to vulnerabilities in (1) bank and (2) household balance sheets:

- With 60 per cent of their lending for housing, Australian banks are very exposed to the housing market, although this risk is offset by lending standards and capital.On the former, Bullock argued that ‘the evidence suggests that lending standards overall have been maintained in the face of very strong demand for housing… in contrast to 2014-2017 when there were signs that lending standards were declining.’ Meanwhile, the RBA is keeping a close watch on trends in loan to valuation ratios and debt to income ratios.At the same time, banks have further bolstered their capital positions since the GFC and ‘stress tests undertaken by the Bank and reported in our October 2020 Review indicate that even a very severe recession and substantial fall in property prices would still leave the banks with capital above their regulatory minima.’

- Most of Australian household debt is mortgage debt and – aside from the implications of household default risk for bank balance sheets – another potential risk channel is via the impact of household balance sheets on consumption.Bullock warned that ‘over-exuberance’ in the housing market could see some households over-borrow, making them more likely to have to later cut their consumption in the face of any shock to incomes. If current rapid price rises ‘ultimately prove to be unsustainable they could lead to sharp declines in price and turnover in the future. This in turn could result in reduced spending, both directly as a result of a decline in turnover and through the wealth effect.’

Bullock also discussed the potential policy response to housing risks, noting that ‘Unlike in 2014 and 2017, the concerns…are not specific types of lending such as investor or interest only lending. So the tools used at that time are not really appropriate at this time. This suggests that if there were to be a need for so-called macro-prudential tools to address rising risks, they should be targeted at the risks arising from highly indebted borrowers. Tools that address serviceability of loans and the amount of credit that can be obtained by individual borrowers are more likely to be relevant’ and concluded her speech by noting that the RBA was ‘continually assessing’ the need for such macro-prudential tools. Although the speech doesn’t state this explicitly, the odds of a macro-prudential policy intervention look to be on the rise.

Closely related, here is the RBA submission to the Inquiry into Housing Affordability and Supply in Australia (pdf). Some points of note include:

- Higher house prices have been driven by a combination of rising incomes, declining nominal interest rates, financial liberalisation and higher rates of population growth.

- While the house price to income ratio has risen, this is only one metric of affordability: another is the cost of servicing mortgage debt relative to income and on this measure lower interest rates mean affordability has actually improved considerably for existing home owners

- For those trying to buy for the first time, however, higher prices have increased the size of deposit needed at the same time as relatively low-income growth has made it harder to accumulate that deposit.

- Rental affordability is becoming a more important issue as the share of Australians renting increases. The latter had risen from around one quarter in the late 1990s to around one third by 2018.

- Almost all the supply of housing already exists, hence factors such as regulation only affect the supply coming from the flow of newly built housing – which in any one year will only lead to an incremental change in the housing stock. It follows that while some regulatory and other changes could improve the responsiveness of construction, there are limits to the scope to meet increased demand with increased supply.

- Despite slower population growth due to the pandemic, house prices have continued to rise, perhaps reflecting increased consumption of housing per household, as some buyers sought more space.

- One of the key challenges for supply over coming decades is that as populations increase and cities expand, some households will need to live further away from the centre of major cities (requiring new infrastructure investment) and/or acceptfurther increases in higher-density housing.At the same time, the pandemic has been associated with a shift in preferences towards houses, which is consistent with a demand for more, not less, space.

- Temporary state and federal government schemes in response to the pandemic have driven an increase in building approvals that will boost housing supply over coming years, but because such schemes also increase demand, the overall effect on house prices is ambiguous.

- The supply of new public housing has been much lower in most periods since 2000 than in previous decades (the exception is the 2009-2012 Social Housing Initiative in response to the GFC) and growth in social housing has failed to keep pace with growth in the number of households and fallen as a share of the housing stock.

- Warwick McKibbibin in the AFR suggests that any review of the RBA should focus on the future, and ask whether Australia’s central bank should persist with the current inflation targeting framework or consider an alternative such as nominal income targeting, consider if the structure and operation of the RBA board is still relevant, and assess whether the present balance between accountability and independence remains appropriate.

- Also from the AFR, Saul Eslake doesn’t like Western Australia’s GST deal while on the other side of the debate, Aaron Morey argues it creates reform incentives.

- Quiggin, Holden and Hamilton reckon that Australia’s National Plan for re-opening needs more flexibility to allow us to respond efficiently to new data on transmissibility, vaccine uptakes and mobility.

- Another submission, this one from the Productivity Commission (PC) on Australian manufacturing industry and the role of government support to the Senate Economics References Committee. The PC argues that government should reduce barriers to research and development (and notes that proposed and actual changes around the R&D tax incentive have increased uncertainty for business), reduce impediments to foreign and domestic investment, provide appropriate supply chain support (including through investment in appropriate infrastructure), manage government procurement processes in a streamlined and cost-effective manner, and support education and training policies aimed at fostering skills and capabilities.

- The ABS published the June quarter 2021 Tourism Satellite Accounts: quarterly tourism labour statistics. According to the Bureau, there were 10,000 (1.5 per cent) more tourism jobs than in the March quarter of this year and 69,100 (11.4 per cent) more jobs than in the same quarter last year. Note, however, that the number of tourism jobs peaked at 745,100 in the December quarter of 2019, and the current level of jobs (at 675,600) is still down 69,500 (9.3 per cent) since the onset of the pandemic and the bushfires that preceded it.

- Also from the ABS: data on casual employment by occupation and industry.

- An FT Big Read on Evergrande. AFR version.

- Michael Pettis on what does the Evergrande Meltdown mean for China.

- Ken Rogoff says China’s real estate sector is so large at an estimated 29 per cent of GDP (construction plus property-related services) that a significant housing slowdown would have a substantial impact on overall growth, even if banking problems are contained.

- This Odd Lots podcast also has some useful background on Evergrande and China’s real estate sector.

- The latest BIS quarterly review includes a summary on recent market developments and special features on monetary policy, relative prices and inflation control and seven decades of international banking. The piece on inflation control suggests that in the (pre-pandemic) era of low inflation, the bulk of changes in the general price index tended to be driven by sector-specific shifts. To the extent that these sectoral shifts are less responsive to changes in overall demand conditions, monetary policy then becomes less effective at influencing inflation, requiring larger changes in the policy stance to achieve a given target. Further, the argument continues, since a substantial share of these sector specific price changes will tend to be transitory in nature, it makes sense for central banks to look through them, as responding by changing the policy stance could easily involve a policy over-reaction. While the data analysis here refers mainly to the pre-COVID period, the piece concludes by noting that if ‘applied to the current context, in which inflation concerns have become more prominent, our analysis also speaks in favour of flexibility in the response…not least because a small number of sector-specific components of inflation have seen especially large increases in recent months.’ Although the essay does go on to caution that this is just one piece of the inflation puzzle, and that it remains critical to ensure that inflation remains low and stable.

- For a different take on inflation prospects, Nouriel Roubini worries that of four potential scenarios– reflation, overheating, stagflation and a growth slowdown – the most likely outcome for the world economy in the near-term is overheating, as easy macro policies, the fading of the Delta variant and its associated supply bottlenecks will leave central banks stuck between a rock (high debt) and a hard place (persistently above target inflation). Then, over the medium term, Roubini warns that a series of persistent negative supply shocks to the global economy including deglobalisation, rising protectionism, demographic aging and climate change could help trigger full-blown stagflation.

- This Wired article claims that the Exponential Age will transform economics. A large part of the argument here is that rapid technological change – manifested for example in the dramatic decline in the cost to process information – transforms business models which in turn creates pressure on existing regulatory frameworks. Another strand is that many of us are not good at understanding exponential growth (an accusation also levelled during the early months of COVID-19) which in turn means that we’re also bad at forecasting it – tending to under- or over-estimate likely change – and likewise are bad at adapting to it as change runs far ahead of the institutions that manage society’s response.

- An Economist magazine briefing on decentralised finance.

- A big WSJ investigation into Facebook – The Facebook Files.

- The World Bank has discontinued its Doing Business report following findings of data irregularities in the 2018 and 2020 reports and the publication of an investigation (pdf) of the same. Some interesting context from Reuters.

- Bloomberg says the global housing market is broken. Soaring prices, rising rents and the associated political pressures and social tensions are creating a wide range of policy proposals including rent caps, landlord taxes, taxes on foreign buyers, bans on foreign buyers, nationalisations and plans for converting vacant offices into housing.

- Also from Bloomberg, fossils are now a ‘hot new asset class’, apparently.

- Do taxes fund government spending?

- A couple of months back, I included a link in the roundup to a piece looking at the dramatic economic divergence between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Here’s some pushback on that piece that takes a different view on what the underlying data actually show.

- Three podcasts to finish up. First, the Australia in the World podcast debates AUKUS.

- Next, while I’m waiting for my physical copy of Shutdown to arrive in the post, in the meantime I’m making do with Tooze podcasts and columns. Here’s a good conversation with the NYT’s Ezra Klein. Or as an alternative, here’s Tooze on the Talking Politics podcast. Note that there’s also new Foreign Policy economics podcast on the way. The man’s productivity is phenomenal.

- Last, Econtalk on the contributions of economists Armen Alchian and Harold Demsetz which discusses their work on property rights, information and the theory of the firm.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content