The RBA believes that Delta will ‘delay but not derail’ the recovery. The latest data though shows that the strain is taking its toll on the global economy. Plus, poor results on the jobs front, though not as bad as last year, and my book of the year (so far).

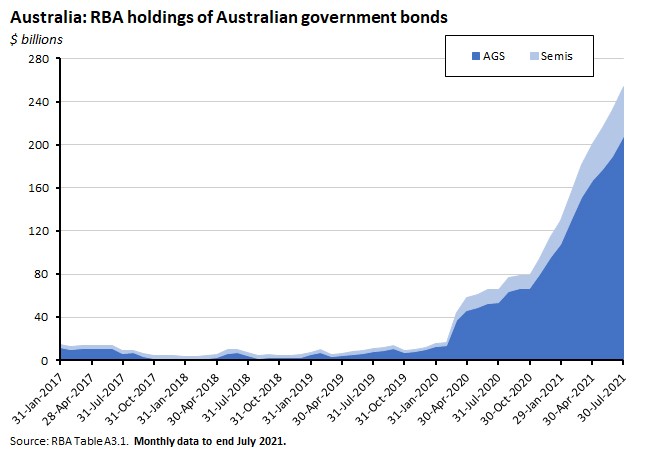

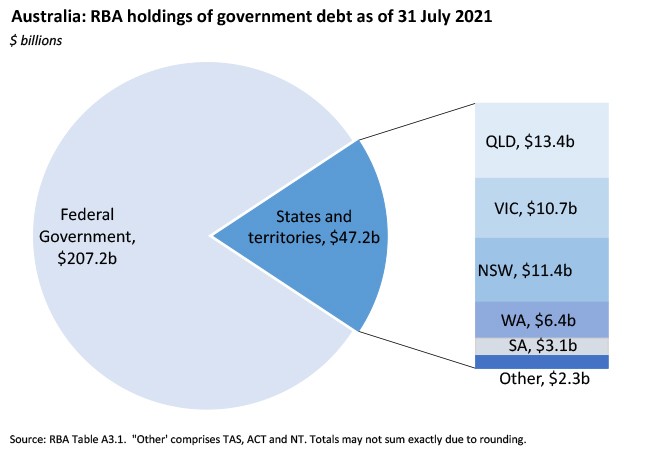

This week saw the RBA stick with the plan it had announced back in July 2021 to taper its program of asset purchases, cutting the rate at which it buys Australian government securities from $5 billion / week to $4 billion / week. But while reiterating its confidence that the Delta outbreak would ‘delay, but not derail’ Australia’s economic recovery, the central bank did acknowledge that the timing of that recovery had been pushed back, uncertainty had increased, and the pace of the recovery when it arrived was now likely to be slower. That assessment also produced something of a compromise in the form of a commitment to run its smaller asset purchase program for longer – at least until mid-February next year. That’s an extension to the previous commitment to maintain quantitative easing until November 2021.

You can hear more about the RBA meeting, as well as the other major economic news on this week’s episode of The Dismal Science.

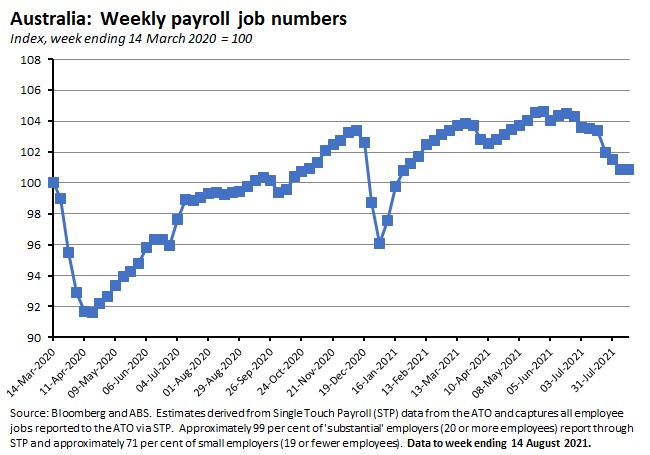

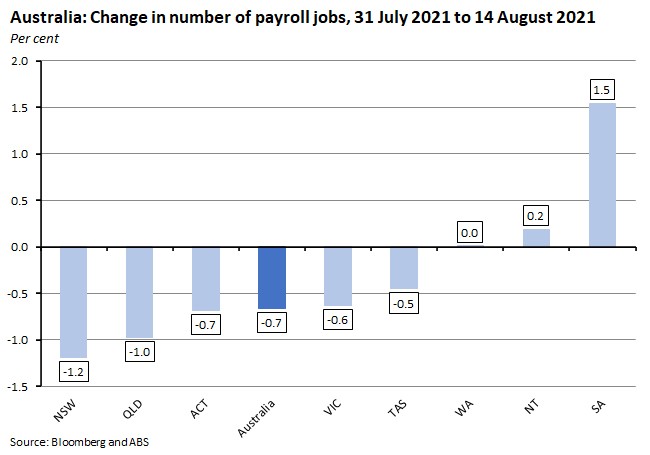

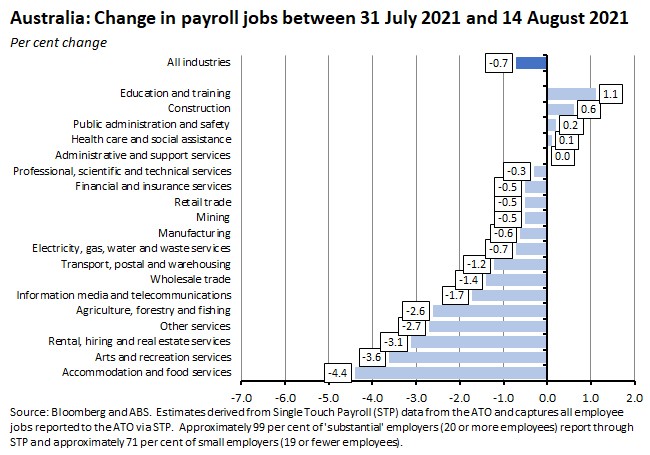

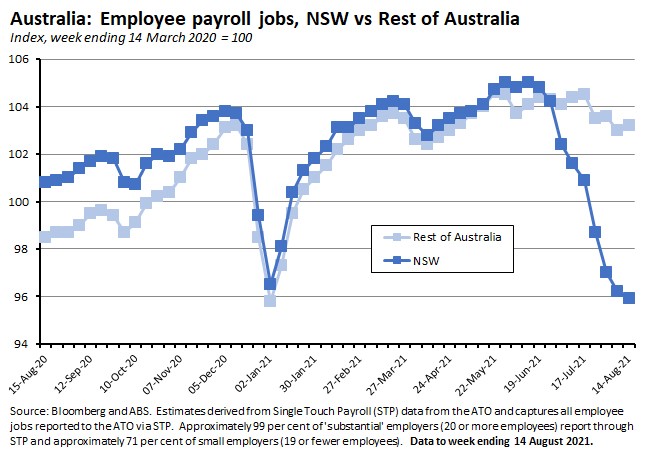

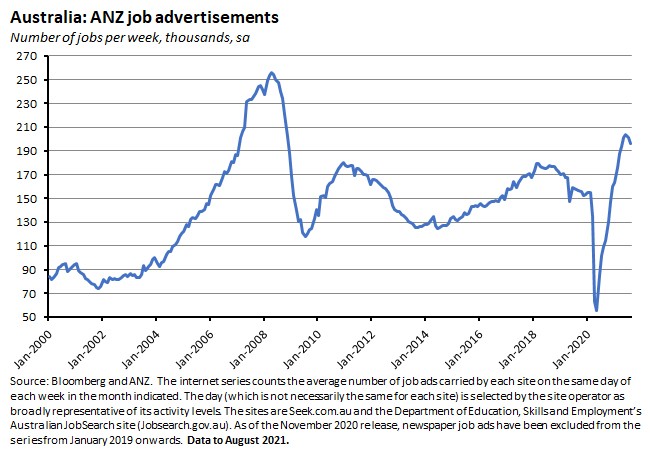

The week also brought more data on Australia’s labour market. Payroll job numbers dropped 0.7 per cent in the first fortnight of August after having already fallen 2.6 per cent over the previous month. The decline was again led by New South Wales, although job numbers were also down in the other three states and territories (Queensland, the ACT and Victoria) that were under lockdown for some or all of the first half of last month. August also saw ANZ job ads fall 2.5 per cent over the month after recording a 1.3 per cent monthly decline in July. The bad news here is that Delta is dragging down not just jobs but also hiring intentions, but the good news is that the cumulative fall to date of 3.7 per cent is very modest when set against the 64 per cent plunge in the number of ads during last year’s national lockdown. Finally, the Labour Account data for the June quarter are mainly of interest as indicators of labour market health pre-Delta, but of note was that the numbers show vacancy rates and the rate of multiple job holdings both hitting record highs earlier this year.

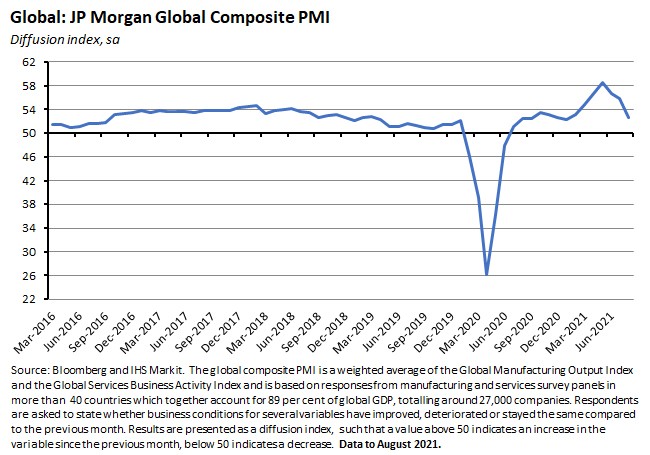

Turning to the world economy, the Composite Global PMI indicates that last month saw world economic growth fall to its slowest rate since January this year, as Delta drove a loss of economic momentum across much of the developed world and saw activity contract in China and Japan.

This week’s readings include: is Australia already in recession?, the missing transparency around government infrastructure projects, the new economics of world cities, global asymmetries and the rise of zero sum thinking, historian Adam Tooze on the pandemic, the Asia-Pacific disaster report, is business travel doomed?, how Delta is shaking up country resilience rankings, and my book of the year (so far).

Finally, stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast . Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

At its monetary policy meeting on 7 September 2021 the RBA Board decided to:

- Maintain the cash rate target at 10bp;

- Maintain the target of 10bp for the April 2024 Australian Government bond; and

- Purchase government securities at a rate of $4 billion / week and continue the purchases at this rate until at least mid-February 2022.

The accompanying statement noted that Australia’s economic recovery has been interrupted by the Delta outbreak and that as a result:

‘GDP is expected to decline materially in the September quarter and the unemployment rate will move higher over coming months. While the outbreak is affecting most parts of the economy, the impact is uneven, with some areas facing very difficult conditions while others are continuing to grow strongly. This setback to the economic expansion is expected to be only temporary. The Delta outbreak is expected to delay, but not derail, the recovery. As vaccination rates increase further and restrictions are eased, the economy should bounce back. There is, however, uncertainty about the timing and pace of this bounce-back and it is likely to be slower than that earlier in the year. Much will depend on the health situation and the easing of restrictions on activity. In our central scenario, the economy will be growing again in the December quarter and is expected to be back around its pre-Delta path in the second half of next year.’ (emphasis added)

On the decision to extend bond purchases at a $4 billion / week rate until at least next February, the statement said that this ‘reflects the delay in the economic recovery and the increased uncertainty associated with the Delta outbreak’ and promised that the Board would continue to review the program in the light of economic conditions and the inflation target.

The RBA also again pledged that it would not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is ‘sustainably within the two to three per cent target range’ and that the ‘central scenario for the economy is that this condition will not be met before 2024.’

Why it matters:

The RBA’s decision to leave both the cash rate and yield curve targets unchanged at 10bp was – as is the norm now – widely expected. Instead, attention was focused on what the central bank would do with its plan to scale back (‘taper’) its weekly rate of government bond purchases. Readers will remember that back in July the RBA had announced that from early September it would cut the size of this asset purchase program from $5 billion / week to $4 billion / week and that it would then review the future of the program in November this year. The onset of Delta and the subsequent economic hit, however, meant that within days of July’s announcement some RBA-watchers were predicting that August’s monetary policy meeting would see Martin Place forced to reverse course in the face of an impending third quarter downturn. Instead, last month the RBA decided to look through the short-term impact of the current lockdowns, focus on what it still judged would be a strong economic performance next year, and leave the planned taper intact. After that August meeting, economists meanwhile have continued to further mark down their forecasts for Q3 GDP and as a result there had been renewed speculation in the run up to this week’s meeting that the RBA would choose not to go ahead with the September taper after all. Again, however, Martin Place has decided to stick to the plan. The taper has gone ahead, albeit in a somewhat modified form.

That modification reflects the fact that the RBA did make a concession to the changed economic circumstances: the asset purchase program will now run until at least February next year, pushing back the date of the planned review from November this year. In other words, while the RBA kept to its commitment to cut the weekly size of purchases, at the same time it increased the longevity of those somewhat smaller purchases. This compromise is a recognition that the Delta outbreak has changed some things. Granted, the central bank hasn’t dramatically altered its base case for the economic outlook: the expectation is still that the current setback will ‘be only temporary’ and that the economy ‘should bounce back.’ What it has done is concede that there is now (more) uncertainty around the timing and pace of the predicted bounce back, and in an implicit recognition that the lessons from the emergence from past lockdowns may not fully apply this time around, that the forthcoming recovery is likely to be slower than the one seen earlier this year.

What happened:

The ABS said that payroll jobs fell 0.7 per cent between the weeks ending 31 July and 14 August 2021 compared to a fall of 1.8 per cent over the previous fortnight. Total wages paid declined one per cent compared to a decrease of 2.2 per cent over the previous two-week period. Payroll job numbers are now down 1.6 per cent over the year since 15 August 2020.

By state and territory, payroll job numbers over the past fortnight fell 1.2 per cent in New South Wales and 1.5 per cent in Greater Sydney, one per cent in Queensland and 1.1 per cent in Greater Brisbane, 0.7 per cent in the ACT, 0.6 per cent in Victoria and one per cent in Melbourne, and slipped 0.5 per cent in Tasmania. Job numbers were unchanged in Western Australia and up 0.2 per cent in the Northern Territory and 1.5 per cent in South Australia.

Jobs in New South Wales are now down 4.9 per cent over the year since 15 August 2020: in every other state, job numbers are up over the year.

Over the two weeks to 14 August this year, job numbers fell in 14 out of 19 industries, with the largest declines in accommodation and food services (down 4.4 per cent), arts and recreation services (down 3.6 per cent), rental, hiring and real estate services (down 3.1 per cent), and other services (down 2.7 per cent). The largest increase was in education and training (up 1.1 per cent).

The number of construction jobs was also up over the fortnight, with 79 per cent of that increase coming in New South Wales, where restrictions on the industry were eased early last month. However, the ABS also noted that the increase in NSW construction jobs was only around 20 per cent of the jobs lost in late July.

Jobs worked by males and females were both down 0.7 per cent over the fortnight; by age group the largest drop was for persons aged 15-19 (down three per cent); by firm size, jobs were down in firms with less than 20 employees (by 3.7 per cent) and with 20-199 employees (down 0.8 per cent) but job numbers were up in firms with 200 employees and over (a one per cent increase).

Why it matters:

After falling 2.6 per cent over the month of July (between the weeks ending 26 June 2021 and 31 July 2021), payroll job continued their decline into the first fortnight of August. The decline in numbers was again led by New South Wales, although job numbers also fell in the other three states and territories (Queensland, the ACT and Victoria) that were under lockdowns for some or all of the first half of August, as well as in Tasmania. New South Wales and Victoria together accounted for 70 per cent of jobs lost over this period.

Once again, job losses by industry were notable in those sectors most exposed to pandemic-driven public health restrictions, with large declines for accommodation and food services and for arts and recreation services in particular.

Finally, note that the estimates reported here only include jobs where a person was paid through the payroll in the relevant pay period. It follows that, because current COVID-related government support payments are paid directly to people or businesses rather than through payrolls, some of the reported drop in payroll job numbers could include employees who remained attached to their job but were temporarily stood down and not paid by their employer in that period.

What happened:

ANZ Job Ads fell 2.5 per cent over the month in August after a (revised) 1.3 per cent monthly decline in July. Ads are still 78.9 per cent higher than in August last year and more than 26 per cent above their January 2020 (pre-COVID) levels.

ANZ said that newly lodged job ads (based on the National Skills Commission’s Internet Vacancy Index which measures the flow of new ads vs. the ANZ job ad measure which captures the stock of total job ads) fell 10.3 per cent in New South Wales in July but were still 24 per cent higher than pre-pandemic. In Victoria, new job ads rebounded following the end of the state’s fourth lockdown.

Why it matters:

Job ads have fallen a cumulative 3.7 per cent over the past two months after having previously risen for 13 consecutive months. As ANZ points out, that modest fall compares extremely favourably with a 64 per cent plunge in the number of ads during last year’s national lockdown.

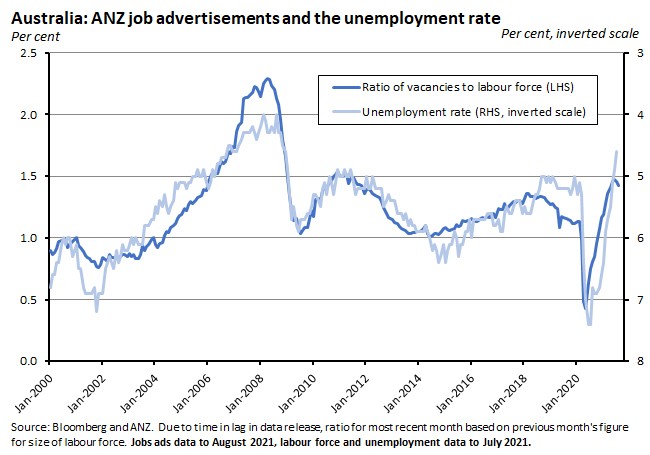

At current levels, Job ads are consistent with an unemployment rate of a bit more than five per cent.

What happened:

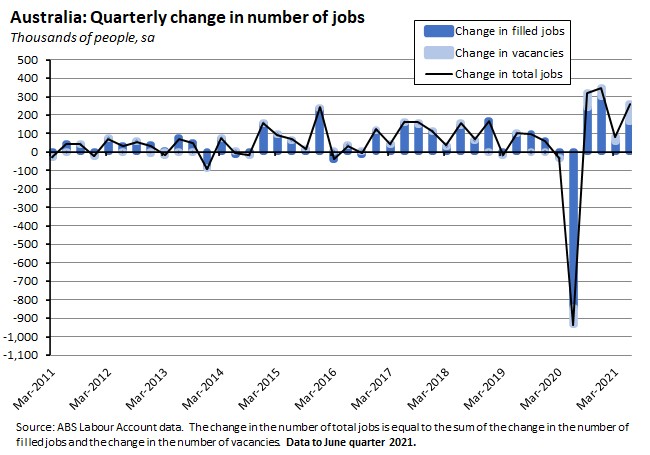

New ABS Labour Account data showed the total number of jobs increased by 262,000 (1.8 per cent) in the June quarter of this year. Filled jobs rose by 167,000 (1.2 per cent) while vacancies were up 95,000 (a 33.4 per cent jump over the quarter).

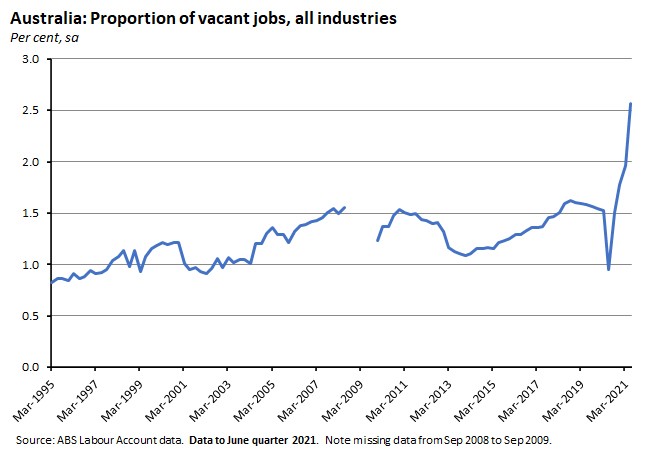

The share of vacant jobs rose to 2.6 per cent in the June quarter this year from two per cent in the March quarter.

The number of secondary jobs increased by 15,100 (1.4 per cent) and the rate of multiple job holding rose to 6.5 per cent.

Why it matters:

The June labour account numbers provide another snapshot of the pre-Delta economy and to that extent already feel dated. Still, the data do offer some interesting evidence on how the labour market was performing before the latest set of lockdowns. For example, the rate of multiple job holding rose to a series high in Q2. Even more strikingly, the June quarter saw the vacancy rate also set a new series record of 2.6 per cent, which is well up on the pre-pandemic vacancy rate of around 1.5 per cent.

We did a deep dive on the Beveridge Curve (the relationship between the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate) at the time of the March quarter 2021 labour account release, noting that there appeared to have been an outward shift in the Beveridge curve since the onset of the pandemic, with higher vacancy rates associated with a given rate of unemployment. The June quarter numbers have continued that trend, combining that record high vacancy rate with an unemployment rate that averaged only a little above five per cent.

One way to interpret this outward shift in the Beveridge Curve is to worry that the Australian labour market has recently become much less efficient at matching jobseekers with jobs. But as noted last time, it’s also possible that the labour market is just struggling to catch up with the scale of recent fluctuations. The process of matching jobs to workers (that is, the search and recruitment process) typically takes time and therefore in the early stages of a labour market recovery, we might expect rises in vacancies to outpace actual hiring decisions, and therefore the increase in the vacancy rate to run ahead of any decline in the unemployment rate. That will be more likely to happen in the case of the kind of rapid bounce back in employment demand that characterised the Australian labour market pre-Delta.

One final point on the labour account data. The quarterly numbers reported here differ from those reported in the monthly labour force survey in several ways. One difference is that the labour account seeks to measure all employed people and all jobs in the Australian economy and includes three groups (people who are not usually resident in Australia, Australian defence force personnel, and people under the age of 15) that are not included in the labour force survey. The difference between the total number of employed persons reported in the labour account and the total number of employed persons reported in the monthly labour force survey is therefore an estimate of the total size of those three groups. In particular, the ABS uses a model to estimate the contribution of short-term / temporary non-residents to the labour force. The Bureau has cautioned that ‘there are inherent limitations in modelling the labour market activity of short-term non-residents, given available data sources. Prior to the COVID period, this modelling uncertainty did not have a material bearing on changes in Labour Account aggregates. However, with the large and unprecedented reductions in short-term non-resident arrivals in Australia during the COVID period, any modelling uncertainty for short-term non-residents is likely to be more visible than it would normally be…[therefore] users should exercise caution when using the derived difference between Labour Force and Labour Account aggregates.’ The Bureau has said that it will introduce a new model for the September 2021 quarter of Labour Account data that will include ‘more robust’ estimates of the magnitudes involved.

What happened:

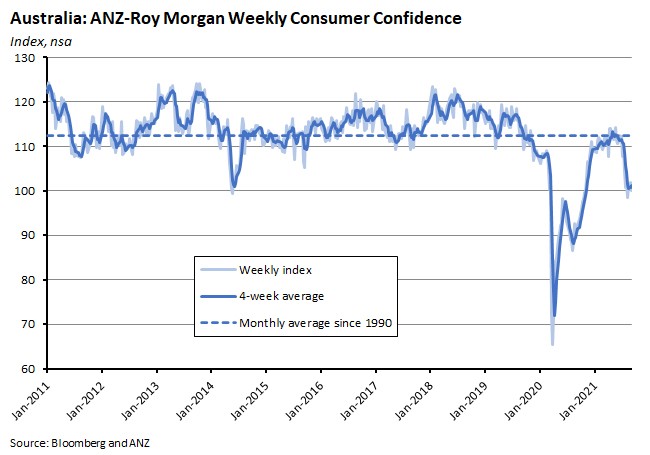

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.8 per cent over the week ending 29 August, taking the index down to a neutral reading of 100 (indicating that the number of optimists is balanced by the number of pessimists). Confidence is now 9.8 per cent higher than in the corresponding week last year.

Four of the five subindices fell last week, with the largest declines in ‘future financial conditions’ (down four per cent) and ‘time to buy a major household item’ (down 3.2 per cent). The only subindex to register an increase was ‘future economic conditions’ (up 1.9 per cent).

Sentiment fell in Sydney (down 5.3 per cent), Brisbane (down 2.9 per cent), and Melbourne (down 0.8 per cent) but rose in Adelaide (up five per cent) and Perth (up 2.3 per cent).

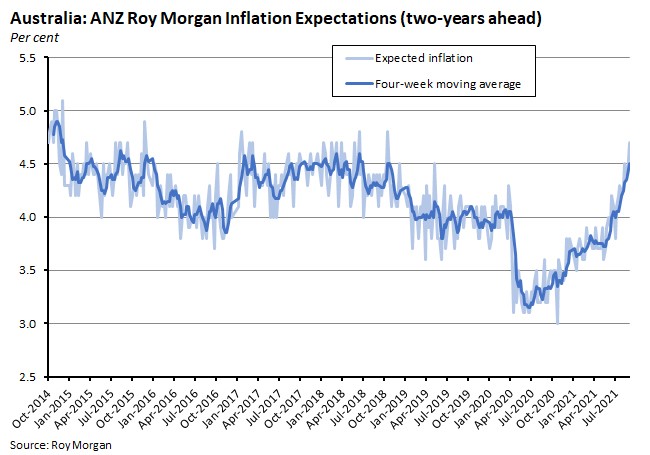

Weekly inflation expectations rose to 4.7 per cent.

Why it matters:

After moving sideways the previous week, consumer confidence fell last week as declines in sentiment in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane outweighed gains in Perth and Adelaide. That divergence in confidence is consistent with the RBA’s story about the uneven impact of Delta on the national economy. Also of note, inflation expectations rose to their highest level since October 2018.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

The J P Morgan Global Composite PMI (pdf) fell from 55.8 in July to 52.6 in August.

The August slowdown in global growth signalled by the index was led by Asia, with economic activity falling in China and Japan. Activity also declined here in Australia. Elsewhere, significant parts of the world economy also reported losing momentum even while their PMIs remained in positive territory.

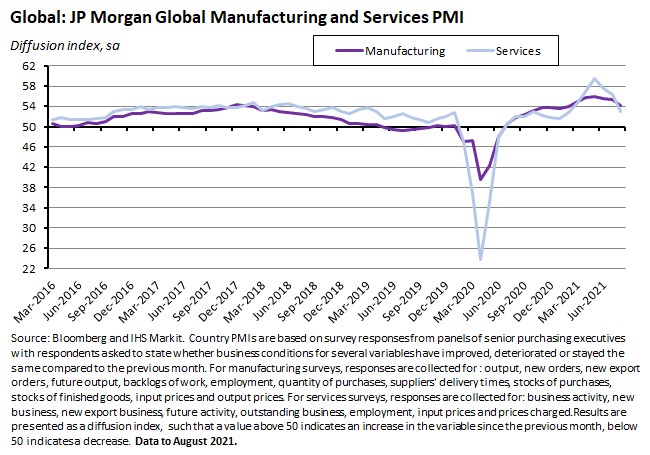

The Global Services Business Activity Index fell to 52.9 in August from 56.3 in July, with growth slowing in the United States, the eurozone and the UK and activity contracting in Japan and China. August also saw the Global Manufacturing PMI (pdf) fall to 54.1 from 55.4 in July, with activity slowing in 24 of the 31 nations covered. Ten markets (including China, Vietnam, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand in the East Asian region) recorded an outright fall in activity as COVID-19 and other disruptions to regional supply chains continued to take a toll.

Why it matters:

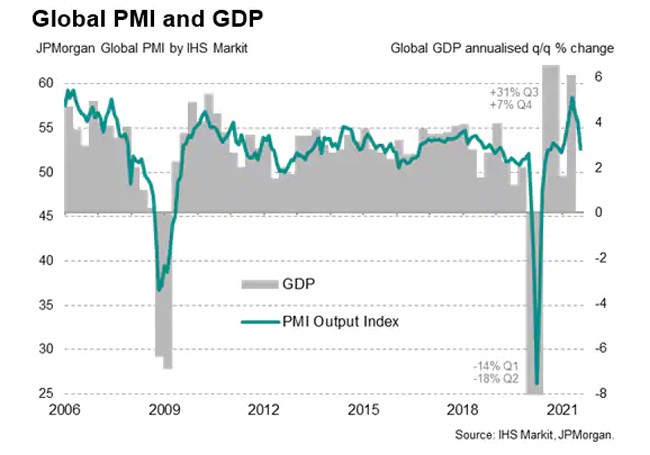

Although the Global Composite PMI signalled a 14th consecutive month of expanding global economic activity, the index also fell to a seven-month low in August as the global economy continued to lose momentum. The overall pace of business activity has now slowed for three consecutive months, and August also saw services activity rise at its lowest rate since February and manufacturing activity slip to a six-month low.

At this level, the PMI is still consistent with positive global growth overall, but it does signal a much weaker third quarter reading than the strong second quarter outcome.

The most recent set of survey results indicate that activity has slowed across a range of major economies, including steep downturns in the United States and the United Kingdom, where rates of expansion have fallen to eight- and six-month lows, respectively. In the United States, separately the August payroll report showed that just 235,000 jobs were created in the month in a steep drop from monthly gains of around a million jobs in June and July as new Delta-driven concerns saw businesses push back reopening plans. The latest Fed Beige Book also reported significant Delta headwinds acting on the economy.

Elsewhere, regional weakness in Asia in general and China in particular has been another key development. In Japan, for example, PMI surveys show output in August falling for a fourth consecutive month and at the steepest rate since August last year. In China the official manufacturing PMI slipped to a reading of 50.1 in August, hovering just above neutral, but the private sector Caixin China General Manufacturing PMI fell to 49.2 in the same month, dipping into contractionary territory for the first time since April last year with survey respondents reporting rising COVID-19 case numbers and public health restrictions as impacting production, dampening demand and making it more difficult to source inputs. The Caixin China General Services PMI told a similar story, with the headline Business Activity Index slumping from 54.9 in July to 46.7 in August, again dropping into negative territory for the first time since April 2020 as panel members cited the impact of efforts to contain the recent surge in COVID-19 cases.

What I’ve been reading . . .

- In the AFR Saul Eslake says that while last week’s GDP result means Australia may have avoided two consecutive quarters of negative growth, nevertheless we’re now in recession.

- Grattan’s Marion Terrill argues that Australian governments are keen to avoid public scrutiny of the funding of infrastructure projects: of 32 projects larger than $500 million that governments have committed to since 2016, Grattan reckons that just eight had a business case (documenting the essential elements of an argument that a particular project is worth building and is the best available option to solve a specific problem) either published or assessed by a relevant infrastructure body at the time money was committed. Terrill also reckons Australia does a poor job on transparency when it comes to tender processes.

- The RBA’s latest Chart Pack.

- Clifford and Freebairn add to case for replacing stamp duty with a more efficient and more equitable tax.

- ABC Business considers how the pandemic has changed shopping centres.

- Kevin Davis on the future of buy now, pay later.

- Richard Holden introduces OzSAGE, a new source of advice on how to reopen Australia.

- An East Asia forum post on realising an ‘early harvest’ for Australia-India trade.

- This Working Paper describes the modelling approach behind Treasury’s macroeconometric model of Australia.

- The Lowy Institute presents a selection of views on September 11, 20 years on.

- The latest issue of the IMF’s Finance & Development magazine focuses on climate change in the run up to this year’s 26th Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP26), with pieces on carbon pricing, sectoral decarbonisation, the role of innovation, green finance and more.

- In the WSJ, Greg Ip sets out the case for a higher US inflation target.

- The Economist explains how the pandemic became stagflationary.

- Also from the Economist, the new economics of global cities.

- Jean Pisani-Ferry examines the ways in which global asymmetries are changing the nature of the global economy. Pisani argues that economic concentration, global value chains, financial centres, digital networks and the enduring supremacy of the US dollar are all contributing to a growing polarisation at the same time as an increased interweaving of economics and politics is leading to the weaponization of economic power. Those changes in turn are all contributing to a shift from positive sum to zero sum calculations.

- An FT Big Read on China and Big Tech.

- Also from the FT, Martin Sandbu sets out some lessons from a working example of a carbon-tax-and -dividend policy.

- Historian Adam Tooze has his new book Shutdown out this week with an ‘instant history’ of the pandemic. Once I have a copy, it will be going straight to the top of my reading pile. In the meantime, Tooze has a long read in the Guardian on Has Covid ended the neoliberal era? and an essay in the NYT on What if the Coronavirus crisis is just a dry run? See also this week’s podcast linkage, below.

- The Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2021 looks at the intersection of COVID-19 with natural hazards and climate change and identifies what it sees as five regional risk hotspots: (1) East and North-East Asia where heatwaves and related biological hazards are increasing alongside existing risks of earthquakes and tropical cyclones; (2) North and Central Asia where high rates of COVID-19 are occurring against a backdrop of drought, land degradation and biological hazards due to climate change; (3) South and South-West Asia and (4) South-East Asia, where some parts of the region are the global epicentres of COVID-19, and where there are intensifying floods, droughts and cyclones; (5) Pacific small island developing states, marked by emerging high rates of COVID-19 along with cyclones and other hazards that have been exacerbated by climate change.

- An Atlantic article on what we actually know about waning vaccine immunity.

- Vanity Fair has a Sebastian Junger piece on the US in Afghanistan that pushes back against the ‘graveyard of empires’ thesis: ‘A vast criminal racket’.

- Bloomberg asks, is Business travel doomed?

- Also from Bloomberg, their latest COVID resilience rankings show that Delta ‘is upending every model of success that’s emerged in the past 18 months, sending economies once ranked as among the best places to be during COVID tumbling.’ China, the United States, Israel and New Zealand all saw their rankings slump between July and August. Australia is currently occupying the 31st spot, between Chile (#30) and Poland (#32). Norway is the new #1.

- The economics of the Downton Abbey effect: British aristocrats and American brides.

- The ChinaTalk podcast once again brings Adam Tooze and Matt Klein together for another entertaining discussion. This one starts off with development models and China’s economic growth but also ranges over hyperinflation, fiat money and more.

- I’ve just finished reading Javier Blas and Jack Farchy’s excellent The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources. Their book provides an engaging overview of the interaction between the commodity traders, financial markets, commodity producers and some of the major geopolitical shifts that have shaped the global economy including post-World War Two decolonisation, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, and the emergence of China as a critical global economic player and the consequent commodity Supercycle. Stories include how the red in tooth and claw capitalists of the trading houses have provided lifelines first for a cash-strapped Soviet Union and then for crumbling Communist states like Cuba after Comecon had imploded; the financing of rebels in Libya and a would-be breakaway Kurdistan; exploiting the South African, Iraqi and Iranian embargoes; helping to pioneer the financialisation of the oil market; grabbing assets in the ‘biggest closing down sale in history’ in post-Soviet Russia; running what looked like an alternative central bank during the Zimbabwe hyperinflation; the global food and financial crises of 2008; and much more. The leading contender for my book of the year at this point.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content