At its 6 July 2021 meeting, the RBA decided to stick with the April 2024 government bond as its yield curve target, meaning that the maturity of that target will fall over time. The central bank also said that when its current bond purchase program comes to an end in early September this year, it will extend asset purchases until at least November 2021, albeit at a lower weekly rate. ANZ Australian job ads delivered a record 13th consecutive increase last month and are now 39 per cent above pre-pandemic levels.

The ABS said that between the weeks ending 5 June 2021 and 19 June 2021 the number of payroll jobs increased by 0.3 per cent following a fall of 0.8 per cent over the previous fortnight. Australia’s rate of job mobility fell to a new record low in the year to February 2021. The final estimate for Australian retail turnover in May 2021 was up 0.4 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) and 7.7 per cent over the year. The ABS reported that total dwellings approved fell 7.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in May 2021 but were still 52.7 per cent higher in annual terms. Spreading state lockdowns saw the ANZ Roy Morgan Index of Consumer Confidence fall 3.9 per cent over the week to 3-4 July 2021. Total new loan commitments for housing rose 4.9 per cent in May 2021 to stand more than 95 per cent above May 2020 levels.

This week’s readings include the RBA and Deloitte providing their views on Australia’s labour market, more takes on last week’s intergenerational report, the costs and benefits of lockdowns, an anatomy of cyber risk, what happens if China’s household wealth is allowed to go global, warnings of a worsening ‘two track’ global economic recovery, why trade is good for your health, the perils of paradigm economics and a bit of holiday/lockdown fiction.

Finally, stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast .

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

At its monetary policy meeting on 6 July, the Reserve Bank Board decided to stick with the April 2024 government bond as the target bond for its yield curve control (YCC) policy while keeping the 10bp yield target. The central bank also said that it would continue to purchase government bonds after the current asset purchase program ends in early September and that it would leave the cash rate target unchanged at 10bp. Governor Lowe later delivered a follow-up speech on the RBA’s monetary policy decision that provided some additional context for the day’s policy announcements.

The statement following Tuesday’s meeting once again noted that Australia’s stronger than anticipated recovery had been bolstered by relatively healthy household and corporate balance sheets, supportive domestic financial conditions, high commodity prices and falling unemployment. But it also continued to caution that:

‘Despite the strong recovery in jobs and reports of labour shortages, inflation and wage outcomes remain subdued. While a pick-up in inflation and wages growth is expected, it is likely to be only gradual and modest.’

And in his follow-up speech, Governor Lowe provided some additional detail on the labour market, explaining that:

‘One issue we are watching carefully, though, is how the balance of supply and demand in the labour market is being affected by the closure of our international borders. There have been increased reports of labour shortages in parts of the country and a step-up in wage increases for some occupations. Even so, wage increases for most Australians are still modest and the expected pick-up in overall wages growth is still forecast to be only gradual.’

The statement also noted recent developments in Australia’s housing market, including rising prices, strong housing credit growth and a increasing share of investor borrowing, and given that context it pledged that the RBA would continue to monitor trends in borrowing and lending standards.

The statement concluded by noting that the RBA ‘will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the two to three per cent target range’ adding that under its central scenario for the Australian economy, ‘this condition will not be met before 2024’. The latter wording marked a shift from the previous phrasing that had said that a rate rise was ‘unlikely to be until 2024 at the earliest.’

Why it matters:

Breaking a run of largely uneventful monetary policy meetings this year, the RBA had already flagged that this month’s meeting would see it make two critical decisions, one on the future of YCC and one on the future of its quantitative easing (QE) or asset purchase program, and the central bank duly delivered. In addition, the Governor’s speech meant that we also got an update on the RBA’s thinking around the future of the cash rate target itself, plus some brief thoughts on the economic implications of recent lockdowns.

First, on YCC the RBA decided to stick with the April 2024 bond and not shift to targeting the November 2024 bond. It also kept the target yield at 10bp. As Governor Lowe’s subsequent speech explained, this decision saw RBA considering the likelihood of an increase in the cash rate target over a three-year window which could potentially extend out to November 2024. In that context, he said,

‘… we are no longer looking over a cliff but instead transitioning from recovery to expansion. This improvement has widened the range of plausible scenarios for the cash rate. Our central scenario continues to be that the condition for an increase in the cash rate will not be met until 2024. But there are alternative plausible scenarios as well. This means that probabilities have shifted and the decision to adjust the approach to the yield target reflects this shift in probabilities.’

By sticking with the April 2024 bond, the result is the maturity of the yield target will now decline over time. All of which was pretty much in line with market expectations.

Second, on QE, the RBA said it would continue to purchase bonds after the expiration of the current asset purchase program in early September. It also said it would maintain the current 80/20 spilt between Australian Government Securities and the securities issued by the states and territories. However, there will be a ‘tapering’ in the size of support, with the central bank scaling back the size of purchases to $4 billion/week from $5 billion/week under the current program. Furthermore, the RBA board will review this new rate of purchase at its November meeting. Why a November review? Lowe explained that:

‘…reviewing the situation in November strikes the right balance. It allows the possibility of a timely recalibration of the Bank's bond purchases in either direction. And it also provides as much guidance about future bond purchases as we reasonably can in an uncertain world. We are not locked into any particular path and bond purchases could be scaled up again if economic conditions warrant.’

Lowe also emphasised that the step-down in the weekly rate of bond purchases should not be interpreted as ‘a withdrawal of support by the RBA,’ arguing that the impact of QE came via the total stock of bonds purchased and not the flow of those purchases. By mid-November of this year, Lowe estimated, the RBA’s cumulative bond purchases will have reached $237 billion or about 30 per cent of Australian government bonds on issue and 15 per cent of state and territory bonds.

Next, on the cash rate, the combination of the statement and Lowe’s speech provided a little more nuance to the RBA’s forward guidance. As already noted above, the statement tweaked the wording on the likely timing of a future rate move, softening it from the previous ‘unlikely to be until 2024 at the earliest’ to ‘not…before 2024.’ A change that has been flagged by RBA-watchers as indicating a more hawkish policy stance. The Governor’s speech then provided some additional context, with Lowe emphasising that (1) the RBA would not increase the cash rate until actual inflation was sustainably within the two to three per cent target band, (2) that for this to be the case ‘it is likely that wages growth will need to exceed three per cent’ but also that (3) ‘this focus on wages does not mean we have a target for wages growth or that wages growth necessarily has to have cleared a specific benchmark before we adjust interest rates.’ Rather, the RBA’s thinking is that (4) ‘history teaches that sustained changes to the inflation rate are accompanied by sustained changes in growth in labour costs.’ And again – despite the RBA’s repeated mantra that it does not expect to hike the cash rate before 2024 (a mantra that was repeated in the sentence following the one below):

‘the condition for an increase in the cash rate depends upon the data, not the date; it is based on inflation outcomes, not the calendar.’

In other words, data- (or state-) based forward guidance will dominate calendar based forward guidance, giving the RBA space to act before 2024 should the data warrant it. Financial markets are already bought into this logic and expect that the data flow will see the RBA start hiking the cash rate well before 2024.

Finally, the Governor also took the opportunity to say that the RBA was relatively sanguine on the implications of recent lockdowns for the economic outlook, stating that:

‘The recent outbreaks of the virus and lockdowns will affect the strength of the recovery in the near term. But Australia's experience has been that once an outbreak is contained and restrictions are eased, the economy bounces back quickly. Recent events have, however, reminded us again that it is difficult to predict the future. It is possible that we will experience further setbacks and we need to be prepared for this. But it is also possible that we experience further positive surprises for the economy; over most of this year we have had a run of better-than-expected data and this could continue.’

What happened:

ANZ Australian Job Ads rose three per cent in June this year to 211,854. That was up 39.1 per cent on January 2020 (pre-pandemic) levels.

Job ads have now delivered a record 13 consecutive months of rises and at current levels are consistent with a likely June unemployment rate of around five per cent (vs an actual unemployment rate of 5.1 per cent in May).

The elevated number of job ads is also consistent with last week’s ABS vacancies report, which hit a record high in May 2021.

What happened:

The ABS said that between the weeks ending 5 June 2021 and 19 June 2021 the number of payroll jobs increased by 0.3 per cent compared to a fall of 0.8 per cent over the previous fortnight (original basis). Total wages paid rose by 0.4 per cent following a 0.8 per cent decline over the previous two weeks. The number of payroll jobs is now 3.4 per cent above the level recorded in the week ending 14 March 2020.

The number of payroll jobs rose in every state over the past fortnight, with the size of increase ranging from 0.1 per cent in New South Wales and Western Australia to 0.6 per cent in the ACT.

By industry, the biggest increases over the past fortnight were in retail trade (up 1.7 per cent), accommodation and food services and transport, postal and warehousing (both up 1.4 per cent) while the largest declines were suffered by agriculture, forestry and fishing (down 1.6 per cent), health care and social assistance services and arts and recreation services (both down one per cent).

Why it matters:

Over the past month, payroll jobs numbers are down slightly (by around 0.5 per cent) but are still more than three per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The latest data show jobs in Victoria recovering from that state’s lockdown with numbers up 0.4 per cent in the fortnight to 19 June 2021 as restrictions were eased. That increase followed a fall of 2.1 per cent over the previous fortnight. The ABS also noted that accommodation and food services in Victoria showed some early signs of recovery, rising 6.4 per cent across the fortnight, compared with national growth of 1.4 per cent. And it also pointed out that the state’s lockdown ‘had a more pronounced impact on payroll jobs in the Greater Melbourne region than in the Rest of Victoria. However, the early signs of recovery in payroll jobs were also more evident in Greater Melbourne.’

Finally, note that the Bureau cautioned that payroll jobs and wages data during June and July ‘reflect a greater variation in business reporting, around the end of the financial year,’ which could result in a higher level of variation in payroll jobs and wages estimates and revisions.

What happened:

The ABS published three new releases on job mobility, potential workers and underemployed workers. These will now replace the single Participation, Job Search and Mobility, Australia release.

On job mobility, the ABS reported that during the year ending in February 2021, only 975,000 people or 7.5 per cent of employed people changed jobs. That was the lowest annual job mobility rate on record.

On potential workers, the Bureau said that in February 2021 there were 20.7 million people in Australia’s usually resident civilian population who were 15 years or over, of whom: 13 million were employed; 2.2 million were not working and wanted to work (of whom 808,000 were unemployed) and 1.7 million people who were not working and were available to start work immediately; and 5.5 million people who did not want to work, including 2.83 million retirees.

And on underemployed workers, the ABS said that, in February 2021, 1.6 million people (12 per cent of the employed) wanted to work more than their usual hours while a further 0.6 million had had their hours reduced but would have preferred to work their usual hours.

Why it matters:

These three new data releases offer a more granular look at some key features of Australia’s labour market, including in particular trends in job mobility. Here, the numbers show that the impact of the pandemic has been to exacerbate a long-running trend of declining mobility, which hit a new record low during COVID-19.

According to the ABS, job mobility fell in five of the eight major occupation groups in 2021 relative to 2020. The largest falls were for managers (down from 7.3 per cent to 5.2 per cent), professionals (eight per cent to 6.5 per cent) and machinery operators and drivers (9.4 per cent to 7.9 per cent), which the Bureau notes were also those occupations less impacted by falls in employment early in the pandemic. Mobility also declined for sales workers (from 11.1 per cent to 9.8 per cent) and for technicians and trade workers (8.7 per cent to 7.9 per cent). In contrast, job mobility increased for labourers (up from 7.7 per cent to 9.2 per cent) and community and personal service workers (8.6 per cent to 9.7 per cent). It remained stable for clerical and administrative workers (at 7.1 per cent).

By industry, the largest increase in job mobility was in accommodation and food services (a rise from 14.3 per cent to 17.1 per cent) and the largest decline was in rental, hiring and real estate services (a fall from 11.3 per cent to 6.8 per cent).

What happened:

According to the ABS, the final estimate for Australian retail turnover in May 2021 rose by 0.4 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) and was up 7.7 per cent relative to May 2020.

The ABS also reported that the value of total online sales fell 4.8 per cent in May 2021 (seasonally adjusted), following a fall of 4.1 per cent in April 2021, and a rise of two per cent in March 2021. As a share of total sales, online sales edged lower to 9.1 per cent in May this year from 9.2 per cent in April. They had reached a peak of 11.1 per cent in April 2020.

Why it matters:

The ABS preliminary estimate for retail turnover in May was 0.1 per cent, so the final estimate of 0.4 per cent growth represents a decent upgrade, driven by upgrades for turnover in Victoria (revised from a fall of 1.5 per cent in the preliminary release to a smaller fall of 0.9 per cent) and New South Wales (revised from a flat result to a 0.5 per cent increase).

Retail turnover in May was influenced by the Victorian lockdown from 28 May onwards as well as by some recovery in spending in those states recovering from restrictions in April. Both the overall level of turnover and the performance by industry continues to reflect the distorting effect of the pandemic, with total turnover continuing to run comfortably above its pre-COVID levels.

The monthly increase in May was led by increases in food retail and in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services.

What happened:

The ABS reported that total dwellings approved fell 7.1 per cent (seasonally adjusted) in May 2021 but were up 52.7 per cent relative to May 2021.

The ABS also said that the value of total building rose 4.5 per cent over the month. The value of total residential building dropped 6.7 per cent (comprising a 5.8 per cent decline in new residential building and a 12.7 per cent drop in residential alterations and additions) but this was more than offset by the value of non-residential building rising 28.5 per cent, driven by a large rise in public sector projects approved in May.

Why it matters:

Building approvals fell for a second consecutive month in May, this time dragged down by a drop in approvals for private sector houses. The latter had hit a record high in April but the end of the HomeBuilder grant, which was introduced back in June 2020 but came to an end on 14 April this year, is likely to have had an impact on May’s numbers and will also influence the data going forward. Still, the absolute level of approvals, particularly for houses, remains well up on pre-pandemic levels.

What happened:

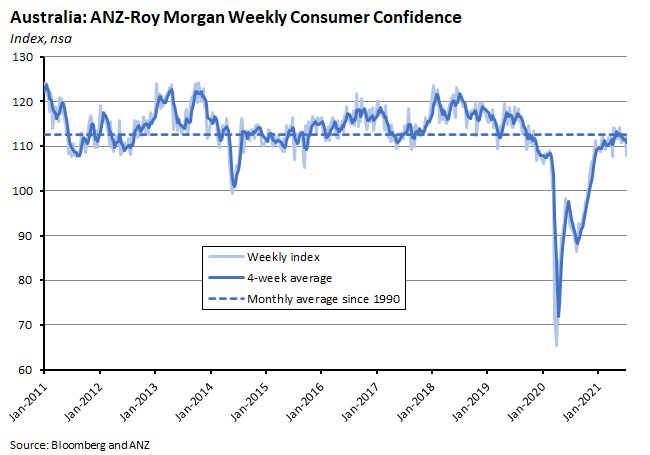

The ANZ Roy Morgan Index of Consumer Confidence fell 3.9 per cent to an index level of 107.8 over the week to 3-4 July 2021.

All five subindices recorded falls, with the largest percentage declines for ‘current economic conditions’ (down seven per cent), ‘time to buy a major household item’ (down 4.4 per cent) and ‘future economic conditions’ (down 4.1 per cent). Current and future financial conditions also declined, but by a more modest 2.6 per cent and 1.9 per cent, respectively.

Why it matters:

Confidence has now slipped back to levels last recorded in early April this year, dragged down by the spread of lockdowns across Australian cities and states. The fall in confidence was particularly sharp in Sydney (down 8.9 per cent) but confidence also declined in Brisbane (a 7.7 per cent drop), Adelaide (down 6.5 per cent) and Melbourne (down 2.7 per cent).

What happened:

Last Friday, the ABS said that total new loan commitments for housing rose 4.9 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in May 2021 and were 95.4 per cent above May 2020 levels.

The value of new loan commitments to owner occupiers rose 1.9 per cent month-on-month and 88.4 per cent year-on-year while the value of new loan commitments to investors rose 13.3 per cent in monthly terms and 116 per cent in annual terms.

Personal fixed term loans rose 5.6 per cent over the month in May and were 42.2 per cent higher over the year.

Why it matters:

Lending for housing turned in another strong monthly increase in May this year (but note that the dramatic annual numbers also reflect base effects driven by the very weak lending result in May 2020). Lending to investors took the lead, with the 13.3 per cent monthly jump taking the value of this category of lending up to its highest level since June 2015. With the RBA and APRA focused on the level of household borrowing and the quality of lending standards, the shift to a growing role for investor lending will be sending some warning signals.

What I’ve been reading . . .

- A second speech from RBA Governor Philip Lowe, this time on the labour market and monetary policy. Reflecting on Australia’s strong labour market recovery, Lowe made the familiar point that ‘the positive surprises on jobs have not been matched with equivalent surprises on wages and prices,’ going on to note that this ‘combination of surprisingly positive employment growth and subdued wages growth had become a familiar pattern before the pandemic.’ He looked to supply side explanations for this development, including rising participation rates powered in particular by the increased availability of flexible and part-time work; the pre-pandemic ability of businesses to draw on overseas labour markets, leading to a flattening of the supply curve of labour such that a given shift in demand produced a smaller effect on wages; and relatively high rates of underemployment that saw hours of work became an increasingly important margin of labour market adjustment relative to the number of employed workers. Lowe argued that all three factors meant that labour demand has been met by a strong supply response which in turn has limited any changes in wages. He then added his previous comments about firms’ ‘laser-like focus on cost control’ to his diagnosis of current labour market conditions. While COVID-19 border restrictions have clearly changed at least some of this picture, Lowe’s view was that enough of it remained true to make it ‘likely that the unemployment rate will need to be sustained in the low fours for the Australian economy to be considered to be operating at full employment’ and that underemployment would also need to fall further.

- See also Deloitte on Australia’s changing labour market.

- The RBA’s July chart pack is now available.

- In the AFR, Steve Grenville says blame the US Fed for low interest rates, not the RBA.

- Two takes on last week’s Intergenerational Report from Inside Story. First, John Edwards reckons that the Intergenerational Report signals an important shift in Australia’s economic debate. Edwards is a bit of a fan of IGR 2021 (‘it is pretty good. Actually, very good’) and his big conclusion is that the IGR ‘officially frees Australia of the politics of debt obsession. It clearly isolates Australia’s long-term economic challenge not as government debt, not as rising healthcare or aged care costs, not as a growing tax burden, and not as an ageing population and slower population growth...The outstandingly crucial issue, it shows, is the growth of productivity.’ Second, Adam Triggs has some suggestions on how to boost productivity growth: a big push to deliver a large number of small-scale microeconomic reforms.

- A new Regional Movers Index.

- Grattan examines the case for making COVID vaccinations compulsory.

- This recent NBER working paper on the impact of COVID-19 policy responses on excess mortality (pdf) has drawn a fair bit of media attention. These two pieces from the Conversation offer somewhat sceptical takes on its findings.

- Related, The Economist provides a more general overview of attempts to assess the costs and benefits of lockdowns.

- The OECD Employment Outlook 2021 estimates that around 22 million jobs were lost across OECD countries in 2020 compared to 2019 and that, despite a partial recovery, there are still over 8 million more unemployed than before the crisis. Comparative labour market analysis shows that Australia has outperformed most of its OECD peers.

- An anatomy of cyber risk.

- Bloomberg’s latest COVID resilience rankings. Australia is now a still creditable #7, albeit down from a high of #2 in February this year.

- Bloomberg asks when (or if) China will overtake the United States to be the world’s largest economy? (Note that if GDP is measured at purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates, China is already number one).

- An FT Big Read considers the potential implications for the global economy if Chinese household wealth went global.

- The IMF worries that the world economy is experiencing a worsening ‘two-track’ recovery, driven by big differences in vaccine availability, infection rates, and governments’ ability to provide policy support.

- In the WSJ, Greg Ip writes that US antitrust policy has shifted focus from maximising consumer welfare to concerns about ‘undue political and economic power’ and, as a result, is likely to be increasingly politicised.

- The CATO Institute on why trade is good for your health.

- Andres Velasco on the perils of paradigm economics.

- Finally, thanks to some school holiday leave plus Sydney lockdowns I managed to squeeze in a little bit of holiday (non-economics) reading this week: Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford and Tomorrow by Chris Beckett. In each case there are previous works by the authors that I prefer, but I still enjoyed both books quite a bit.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content