Deep tech, AI and the rapid rise of neobanks are changing the way consumers and businesses manage their finances. What will the next decade of banking bring?

Consider a short-term property rental company with a digital wallet linked to its commercial bank. The wallet receives payments from guests, pays out maintenance fees and taxes, hires cleaners and other essential services autonomously, then makes the monthly mortgage payment.

Or think about an electric vehicle that automatically charges itself with power and pays. If it has a crash, it handles the insurance claim, with data collected by its sensors sent directly to the insurance companies.

These visions, outlined in the World Economic Forum (WEF) report, Forging New Pathways: The Next Evolution of Innovation in Financial Services, are set to become reality in the coming years as new technologies — including big data, machine learning, blockchain and cloud computing — converge to allow faster and more individualised services from financial institutions.

Even home loans could be automated. For instance, the property owner’s finance app would constantly scan the market for a better home loan rate, calculating if it’s worthwhile swapping banks. If it is, the app automatically transfers the homeowner’s accounts to the new bank.

While these scenarios lie in the not-too-distant future, the use of technology is already driving significant changes in the way business is conducted. Here are some key trends altering how organisations manage their finances.

Open banking

Introduced as a pilot program in July 2019, open banking got off to a slow start in Australia, but its impacts will be felt in coming years — not just in finance but also more broadly throughout the economy.

Under this system, which was officially adopted in July 2020, banks are required to share customers’ transaction data with them. Customers can then pass this on to other financial services providers or apps to gain access to more competitive products — including credit cards, savings accounts, joint accounts, home and investment loans — and better financial services.

These might include account aggregation services, to give a customer an overall view of their financial position across banks and, in the case of business customers, to help with working capital management. There is also potential for comparison apps to take the data of consumers or businesses to see if they can get a better deal with another institution.

Paul Wiebusch, open data leader at Deloitte, says open banking’s move towards a broader consumer data right will require a range of industries, such as energy, telecommunications and aviation, to also share data and this raises some key questions for directors.

The first is around the profitability of data collection. “How much of the economics of those businesses are based on that data capture and how would they be impacted if that was shared by the consumer?” asks Wiebusch.

Secondly, there’s the question of the opportunities that data sharing might open up for companies: “How might the propositions we are offering to our customers be modified and enhanced if we were able to have consumers share with us data from other sectors in order to provide new or different or better services or products to those customers?”

Instant payments

Australian consumers and businesses have quickly adopted the instant payments on offer from the New Payments Platform (NPP). Along with enabling bank payments within seconds, the NPP allows payments to be accompanied by large amounts of data, rather than the maximum 18-character description we’re used to seeing on our bank statements. This will not only make reconciliation of bill payments easier, but will also pave the way for new services, such as seamless property transfers that take place when payment is made, travel bookings that avoid credit card surcharges, and capital raisings where the entire transaction is conducted via a smartphone app.

New Payments Platform Australia (NPPA), which oversees the service, is working to introduce a mandated payments service allowing third parties to initiate payments that are then approved by the account holder. The NPPA says this capability will “enable a range of use cases, including a better alternative to current direct debit payments, merchant-initiated ecommerce and in-app payments”. It would allow, for instance, a corporate banking customer to authorise a cloud accounting software provider to manage their finance functions, such as payroll.

The capability will tie in with open banking and the consumer data right, because not only will customers be able to authorise an institution or app to access and analyse their data, they can authorise it to initiate transactions on their behalf, too — perhaps switching energy providers if there’s a cheaper deal in the market.

Rise of the neobanks

The major banks still have the bulk of the market share in Australia (as of 2019, they managed 81 per cent of residential mortgages), but neobanks are nipping at their heels, particularly in consumer banking but also in business.

Neobanks are small, digital startup banks with few or no branches that typically launch with a limited range of products, such as transaction accounts, but not mortgages. Because they are designed from scratch, they don’t have any of the legacy IT systems major banks have and so can introduce changes and new products much more quickly than the Big Four. While they typically target the consumer market, some — such as Judo Bank — are aimed at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). “From the very outset, Judo has been focused on purpose-building an SME challenger bank that goes back to relationship banking as it used to be done,” says David Hornery, a former NAB banker who co-founded Judo in 2016.

What’s changed is that the relationship is underpinned by technology. The entire IT system is in the cloud, freeing bankers to spend more time out of the office and with their customers. Neobanks also draw heavily on data to provide insights into customers and their needs — something the majors are working on.

“Our capacity to evolve technologically through the substantive introduction of machine learning, robotics and artificial intelligence over the course of coming years will also be a key component of our evolution,” says Hornery. “Ultimately, the product innovation, digitalisation and customer focus that the competition introduces is a good thing for industry generally.”

Peer-to-peer lending

Mostly a niche product in Australia, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending will start to challenge the major banks as it grows, says Mark Jones, chief executive of P2P lender SocietyOne. Also known as marketplace lenders, they match people who want to borrow money for a home mortgage or the like with those who want to lend or invest.

Unlike the major banks, which profit from charging an interest rate spread between depositors and borrowers, P2P lenders charge fees. This, they say, allows them to pay higher interest rates to investors and charge borrowers lower rates. Jones describes SocietyOne — which counts Westpac, Seven West Media and News Corp Australia among its shareholders — as a “facilitator”.

So far the sector hasn’t made much of a dent on the financial landscape, although it is growing. In 2017–18, the total amount lent by P2P lenders was $433m, up from $300m the year before and $156m the year prior to that, according to data from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. ASIC’s Moneysmart website advises that many P2P loans are unsecured, and the way operators assess borrowers’ ability to repay their loans varies.

According to Jones, there is a strong desire for alternative investments from institutional investors such as super funds, particularly in the current low-interest rate environment. SocietyOne is creating unit trusts that bundle together a large number of loans and can have multiple investors. It is also creating bespoke unit trusts of minimum $20m for super funds, which can choose the characteristics of borrowers in the trust. “These kinds of structures let us really challenge the big banks more,” says Jones.

The decline of cash

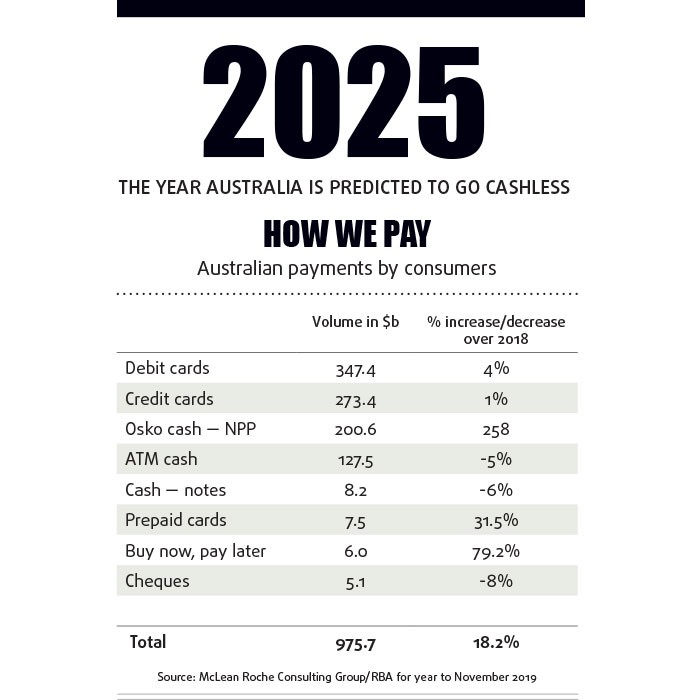

Australia could become a near-cashless society as soon as 2025, with just a small amount of banknotes and coins still in use, according to data analytics firm GlobalData. The trend has been driven by the rise of online shopping, more portable point-of-sale technology, lower transaction fees and the lower cost of digital payments compared with cash — coins and banknotes need to be counted, secured and deposited in the bank.

The COVID-19 crisis and resulting reluctance of consumers to handle physical cash, along with the decision by some retailers to refuse to accept it, have accelerated the transition. GlobalData ranked countries based on how quickly they are going cashless and Australia came in sixth after Finland, Sweden, China, South Korea and the United Kingdom.

What’s more, says GlobalData, Amazon, Walmart and Russian supermarket chain Azbuka Vkusa have launched cashier-less store formats where customers can collect their products and walk out of the store, with beacons, near-field communication or wifi technology taking the payment automatically. This enables retailers to avoid human interaction within stores.

In a white paper published in 2019, the US Federal Reserve said: “It can make economic sense for a business to go cashless: transactions are faster; opportunities for theft are reduced; businesses may be less attractive robbery targets; and stores can eliminate cash-handling costs.”

However, the trend towards a cashless society is not assured. The paper notes that two US state governments have passed legislation banning cashless business to ensure those without credit cards or bank accounts aren’t excluded from economic life.

A brave new finance world

Technologies including artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), 5G and quantum computing are coming together to collectively reshape financial services, bringing new opportunities to companies and consumers alike, says the WEF.

According to Forging New Pathways, increased automation and embedded financial services will allow for seamless transactions for routine activities. A range of cross-industry partnerships will flourish, allowing consumers’ financial and non-financial services needs to be addressed simultaneously.

Take, for instance, the aforementioned EV with embedded digital wallet linked to the owner’s bank account that could pay for tolls and recharging. Or the greatly improved insurance claims experience, where analysis of IoT sensor data could tell the insurer how serious the accident is and whether urgent assistance is required. It could also notify a tow-truck service, organise for the car to be taken to a repairer and book a rental car for the driver.

Ultimately, customers won’t think about financial services, says the WEF. “Perhaps the greatest achievement of the new evolution in financial services will be that many of the changes brought about by emerging technology clusters may not be noticed at all,” states the report.

“That is, a business or individual will find that their financial needs are being met, and financial opportunities available to them are greatly expanded, but this will be accomplished so seamlessly and integrated into one’s life so fully, that the financial services and products themselves will not be front of mind.”

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content