The latest IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO), released this week, warns that the global economy is headed into stormy waters. According to the fund, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to destabilise the world economy, including through a severe energy crisis in Europe and higher international food prices. Persistent and broadening inflationary pressures have also triggered a rapid and synchronised tightening of monetary conditions and a strong appreciation of the US dollar, and there are now risks of both under- and over-tightening by central banks; China continues to struggle with fallout from its zero-COVID policy and the destabilising weakening of its property sector; the risk of monetary, fiscal or financial miscalibration has risen sharply; and financial turmoil may well erupt. The WEO forecasts that more than one-third of the global economy will contract this year or next, while the three largest economies – the United States, the EU and China – will all continue to stall. As a result, the IMF says: ‘the worst is yet to come, and for many people 2023 will feel like a recession.’

Here in Australia, this week’s data once again showed the stark divergence between very subdued household sentiment on the one hand and booming business conditions and decent business confidence on the other. Part of the explanation is that despite households telling survey collectors that they are unhappy with their economic and financial circumstances, on aggregate they have continued to spend. But one of the key risks to the Australian outlook is that that this will change over time. This week’s data did provide some modest evidence of such a shift, with CBA’s monthly Household Spending Intentions index falling in September for the first time since April this year.

The world economy is navigating stormy waters

According to the October 2022 IMF WEO, real GDP growth in the world economy will be 3.2 per cent this year, down from six per cent in 2021, before slowing further to 2.7 per cent in 2023 (output measured at purchasing power parity exchange rates). The IMF forecast for this year is unchanged from the fund’s July 2022 WEO Update, but the forecast for next year has been trimmed by 0.2 percentage points as the world slides further into a broad-based slowdown. The IMF notes that this growth outlook is significantly below the norm for the world economy: global growth averaged 3.6 per cent during 2000-2021 and, aside from the outcomes associated with the big negative shocks of the global financial crisis and the pandemic, the forecast for 2023 would be the weakest outcome since 2001.

In the case of Australia, the IMF thinks the economy will grow by 3.8 per cent this year and just 1.9 per cent in 2023. That compares to April 2022 WEO forecasts for 4.2 per cent and 2.5 per cent growth, respectively.

As noted above, the IMF expects that all three of the world’s largest economies (the United States, China and the eurozone) will slow significantly over 2022 and 2023. It also sees a world afflicted by economic, geo-political and ecological changes, from inflation at multi-decade highs and rapid monetary policy tightening, through Russia’s war in Ukraine, and on to the ongoing impact of the pandemic, particularly in the context of Beijing’s zero-COVID strategy, and a mix of intense heatwaves and droughts that the fund warns provide ‘a taste of a more inhospitable future blighted by global climate change.’

Some modest good news amidst all this gloom is that the IMF says that a decline in global GDP or in global GDP per capita – features often associated with a worldwide recession – is ‘not currently in the baseline forecast.’ That said, a contraction in real GDP lasting for at least two consecutive quarters, which is often used as the definition of a technical recession, is predicted to occur for about 43 per cent of economies (or more than one-third of world GDP), during 2022-23.

The IMF also forecasts that global headline consumer price inflation will rise from 4.7 per cent last year to 8.8 per cent this year (an upward revision of 0.5 percentage points relative to July’s projections) before gradually slowing to 6.5 per cent in 2023 and 4.1 per cent in 2024.

In terms of threats to the central case captured by these projections, the October WEO warns that the downside dominates, with the danger that growth proves to be weaker and inflation higher for longer than in the IMF’s baseline forecast. Key items on the fund’s worry list include: Macro policy mistakes; divergent economic policies and US dollar strength leading to cross-border economic and financial tensions; inflationary forces proving to be more persistent than anticipated; widespread debt distress across emerging markets; the halting of gas supplies to Europe; a resurgence of global health scares; a worsening of China’s real estate woes; and a fragmentation of the world economy that not only undermines international cooperation but that also threatens global trade and capital flows.

The messages of caution and concern are echoed in the IMF’s October 2022 Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR), which maintains a similarly sombre tone, warning that the risks to stability have increased. According to the GFSR, the current period of extreme market volatility reflects ‘the highest inflation in decades and extraordinary uncertainty about the outlook’ with price swings further amplified by a deterioration in market liquidity. The fund warns of the risk of ‘a disorderly tightening in financial conditions that may interact with pre-existing vulnerabilities’ and also points to growing strains in emerging markets and developing economies (where 20 countries are now in default or trading at distressed levels), in China’s property market, and in international housing markets.

While a global recession may not be the IMF’s base case, the risks of that outcome are high and rising.

Australian consumer and business sentiment are still diverging

Here in Australia, increasing interest rates and a rising cost of living – together with increased talk of growing recession risk – continue to take a toll on household confidence. After having staged a surprise rise in September 2022 (last month’s 3.9 per cent rise was the first uptick since November 2021), the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment slipped back 0.9 per cent to a reading of 83.7 in October, taking the index down to lows comparable to the levels reached during the pandemic and the global financial crisis. Three of the five subindices fell this month, with a 0.4 per cent decline for ‘family finances next 12 months’, a 4.2 per cent drop for ‘economic conditions next 12 months’, and a 2.1 per cent fall for ‘economic conditions next five years.’ Partially offsetting these growing concerns about future economic conditions were increases for ‘family finances vs a year ago’ (up 1.1 per cent) and ‘time to buy a major household item’ (up 1.6 per cent). All five subindices are between 14 and 25 per cent below their levels in October 2021, with the overall sentiment index down 20 per cent over the year.

Notably, Westpac reported that the RBA’s smaller-than-expected 25bp rate increase last week likely averted a much steeper drop in sentiment. The survey underpinning this month’s index was conducted between 3 and 6 October and the RBA decision was announced on 4 October. Sentiment amongst those sampled before the RBA decision was a lowly 77.4 – which if consistent across the full sample would have delivered the second weakest sentiment reading on record since the early 1990s recession. But that result was largely offset by much stronger sentiment reading amongst those surveyed after the decision. The index for this second group was 88.7, or more than 14 per cent higher than in the pre-meeting group and five per cent above the September 2022 full index result. However, Westpac cautioned that this ‘relief rebound’ was unlikely to be repeated in coming months, with the RBA expected to deliver two more rate hikes in the last two meetings of the year.

The latest ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence reading also reported a decline, with the index dropping 1.1 per cent to 84.6 in the week ending 9 October. Confidence on this measure is now back at its lowest level since mid-August this year. Here again, there were mixed movements across the survey’s five subindices with falls for ‘current financial conditions’ (down 3.6 per cent), ‘current economic conditions’ (down three per cent) and ‘time to buy a major household item’ (down 4.4 per cent) partially offset by increases for ‘future financial conditions’ (up 1.8 per cent) and ‘future economic conditions’ (up 2.2 per cent). ANZ observed that in this case the weekly fall was mainly driven by a 3.2 per cent drop in confidence among those paying off a mortgage: in contrast, confidence fell just 0.4 per cent for those who own their own home and was up 0.9 per cent for those renting. Household inflation expectations eased slightly to 5.5 per cent last week from 5.6 per cent the week before, in line with a small fall in average petrol prices.

We’ve repeatedly highlighted the ongoing disconnect between sentiment survey results and actual household spending, noting that high employment and high savings have successfully supported the latter despite the former. The latest ABS experimental monthly household spending indicator is broadly consistent with this trend, rising 29 per cent over the year in August 2022 for an 18th consecutive month of annual increases in total household spending. That was up from a 24 per cent year-on-year rise in July. The Bureau did note that the large year-on-year gains reflected a rebound following the COVID-19 Delta lockdowns that had reduced spending in 2021, with the biggest increases occurring in those categories most affected by lockdowns, including clothing and footwear (up 75.8 per cent), hotels, cafes and restaurants (up 64.8 per cent), and transport (up 57.8 per cent). Other categories such as food (up 2.4 per cent) saw much more modest gains. (Note that for this indicator and in the absence of seasonally adjusted data, the ABS advises looking at through the year results and not month-on-month changes.)

In a sign that higher rates may now be starting to impact actual spending, however, the CommBank Household Spending Intentions (HSI) Index did fall 0.5 per cent over the month in September, marking the first monthly decline in the HSI since April this year (remember, the RBA started to increase the cash rate in May), with CBA economists pointing to the impact of higher interest rates on household budgets. The monthly drop was led by falls in health & fitness, home buying, household services and transport. In annual terms, the HSI was up 14.1 per cent, but again, this largely reflects the fact that in September 2021 much of the East Coast was in lockdown. (Note also that this index is in nominal dollars, so given the current rate of inflation, spending in real terms will be considerably weaker.)

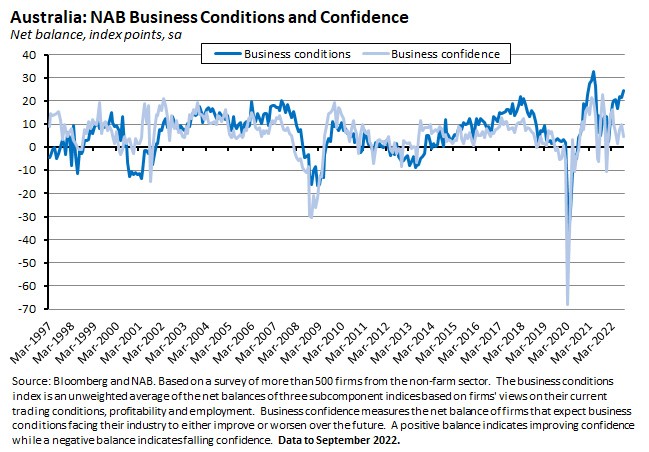

Finally, it’s not just household confidence and spending that are diverging. The same is true for household confidence compared to business confidence and conditions, with the explanation in part likely to be that sustained spending by households. Certainly, businesses continue to enjoy booming current conditions in particular while also remaining relatively upbeat about the future. The September 2022 NAB Monthly Business Survey reported that business conditions rose three points to +25 index points last month, climbing to be above their pre-COVID peak and close to their post-lockdown peak in early 2021. Trading conditions were the key factor behind last month’s rise, increasing by nine points to +39 index points. The other determinants of conditions – profitability and employment – were little changed over the month but remained elevated at +19 and +16 index points respectively. NAB reported that conditions were fairly robust across sectors and most states.

Business confidence did ease last month, falling by five points to +5 index points. Even so, at that level it remains close to its long-run series average and is still in optimistic territory. Moreover, forward-looking indicators such as forward orders (up one point at +15 index points) and the rate of capacity utilisation (down slightly but still at 85.8 per cent) remain very strong.

NAB economists also detected ‘tentative signs that cost pressures may have peaked’. Last month brought a second successive slowdown in the rate of growth of both purchase costs (down to 3.8 per cent in quarterly terms from 4.4 per cent in August and 5.3 per cent in July) and labour costs (down to 3.1 per cent from a 3.4 per cent rate of increase in August and 4.6 per cent in July), alongside a more modest easing in the pace of final product price increases.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ABS experimental monthly business turnover indicator for August 2022 showed month-on-month increases in 12 of the 13 industries covered by the data and annual increases in all 13. The largest increases in monthly turnover were in transport, postal and warehousing (up 8.2 per cent as global supply chain issues continue to ease, and merchandise imports surged to a record monthly high in the same month), other services (up 4.6 per cent) and manufacturing (up 4.1 per cent), with the only fall suffered by information, media and telecommunications (down 0.4 per cent). In annual terms, the largest increases in turnover were for accommodation and food services (up 72.1 per cent relative to a lockdown-influenced August 2021), electricity, gas, water and waste services (up 46.9 per cent) and arts and recreation services (up 45.1 per cent).

Between the weeks ending 3 and 17 September 2022, the number of payroll jobs rose 0.4 per cent while total wages were up 1.4 per cent (wages see increased seasonality around September each year due to the payment of bonuses across multiple industries). Job numbers were up 0.3 per cent over the month and six per cent over the year. The ABS noted that growth in payroll jobs has been slow this year, with average monthly growth over the past six months running at just 0.3 per cent, which the Bureau reckons reflects the tight labour market conditions across the economy.

According to the ABS, overseas arrivals into Australia in August 2022 were down by 53,910 trips over the month to 1,027,700 while overseas departures fell by 26,270 trips to 942,210.

Updated ABS numbers on the value of renewable energy construction reports a significant increase in the level of investment in renewable generation and storage technology, from $865.9 million in 2016-17 to $5.51 billion in 2021-22. While total power generated remained at a similar level over this period, up just 2.5 per cent, the share of renewables in power generated has risen from 16 per cent to 33.4 per cent. The Bureau also notes that while electricity generated by roof top solar is included in electricity generation data (it accounted for 30.3 per cent of all renewable energy produced in March this year) it is not included in the investment numbers.

This week on The Dismal Science podcast we talk about that gloomy IMF outlook and discuss what slowing global growth could mean for Australia. Plus, we discuss this year's Nobel Prize for economics, the latest consumer confidence numbers and more insights from the 2021 Census.

Other things to note . . .

- Last Friday, the RBA published the October 2022 Financial Stability Review. According to the Review and consistent with the IMF’s GFSR, global financial stability risks have increased due to a combination of falling asset prices, increased volatility, rising interest rates and downgrades to the international growth outlook. The Review also warns that the risk of cyber-attacks elevated, and that a significant cyber event could undermine confidence in the financial system and have systemic implications. The RBA also notes that a small share of borrowers with low savings and high debt are vulnerable to payment difficulties due to higher interest rates and falling real incomes: as of August this year, only around one per cent of all variable-rate owner-occupier loans had a loan-to-income (LTI) ratio greater than six and prepayment buffers equivalent to less than one month of payments, while those with an LTI ratio greater than four and prepayment buffers of less than three months accounted for around 6 per cent of all owner-occupier variable-rate loans. For businesses, the Review has a similar message, noting that while most firms are in decent shape, those with high levels of debt and low cash buffers also look exposed to higher interest rates. It also says that in particular the residential construction industry is facing challenges due to rising input costs and shortages or labour and materials. This has eroded profit margins on fixed-price contracts and pushed a number of large firms into insolvency, while higher interest rates are further adding to financial pressures.

- Also from the RBA, a speech from Assistant Governor (Economic) Lucy Ellis on the neutral interest rate. She argues that the neutral rate is ‘best thought of as a long-run concept’ and defines it as ‘the interest rate that keeps growth at trend and inflation constant at target, when no other shocks are hitting the economy…it is where the policy rate settles once all shocks have played out…[it can also be defined as] the level of the policy rate that balances desired saving and investment.’ According to Ellis, the RBA uses nine different models to estimate the neutral real rate which provide a range from negative 0.5 per cent to two per cent. The average across these models implies a neutral real rate of just under one per cent. In terms of the implications for policy, Ellis says there the RBA is not following a mechanistic approach of getting back to (or above) neutral – it ‘is an important guide rail for thinking about the effect policy might be having. It is not necessarily a prescription for what policy should do.’

- The Treasury Roundup 2022 includes pieces on Australian productivity and the global slowdown, competition and productivity growth, and new technologies in the Australian job market.

- The October 2022 Deloitte Access Economics Budget Monitor.

- From the ABS, a snapshot of the economic, social and cultural make-up of Australia on Census Night, 10 August 2021. One in seven of the Australian workforce or more than 1.7 million people now work in the health care and social assistance industry, with particularly strong growth in occupations such as aged and disabled carers and occupational therapists. Alongside the caring economy, the data also show the rising prominence of the digital economy in education and employment: the number of people with an IT qualification is now approaching half a million, the fastest growing qualification in Australia is Security Science, and the number of ICT professionals and managers in the workforce has grown by 86,000 since the last census.

- ABS data on how Australians used their time in 2020-21.

- A new Grattan Report on how to fix the abuse of taxpayer-funded advertising in Australia.

- The opening statement to the House Standing Committee on Economics from APRA Chair Wayne Byres.

- The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2022 was awarded to Ben Bernanke, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig for their research on banks and financial crises. Pop science summary of their contribution here and more technical background here.

- Related, Greg Ip in the WSJ on how Ben Bernanke put his theories into practice during the global financial crisis and Noah Smith’s substack on an econ Nobel for research that saved the world.

- The Economist magazine’s Special Report on the World Economy.

- The US Fed might break the global economy.

- Related, the NY Times Ezra Klein podcast has a long conversation with Adam Tooze on how the US Fed is shaking the global system.

- FT Big Read on how the changing relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia could create a new global energy order.

- A research paper from the World Bank on the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty and inequality. The authors estimate that in 2020 the world suffered the largest single-year increase to global inequality (in this case, mainly inequality between countries) and poverty (an increase relative to baseline of 90 million people in extreme poverty, defined as a daily income or consumption less than US$2.15 per capita) since at least 1990.

- WFH around the world. According to the authors, relative to the WFH revolution, ‘no other episode in modern history has involved such a pronounced and widespread shift in working arrangements in such a compressed time frame. The Industrial Revolution and the later shift away from factory jobs brought greater changes in skill requirements and business operations, but they unfolded over many decades.’ Survey-based estimates from 27 countries suggest that employees value the option to work from home for two-three days per week at five per cent of pay on average, with higher valuations for women, people with children, and people with longer commutes.

- How does popular personal financial advice line up with economic theory? It turns out that while they have diverging views on savings and debt, both approaches make similar recommendations regarding asset allocation, albeit for different reasons.

- The Odd Lots podcast with a deep dive into the turmoil in UK gilt markets.

Already a member?

Login to view this content