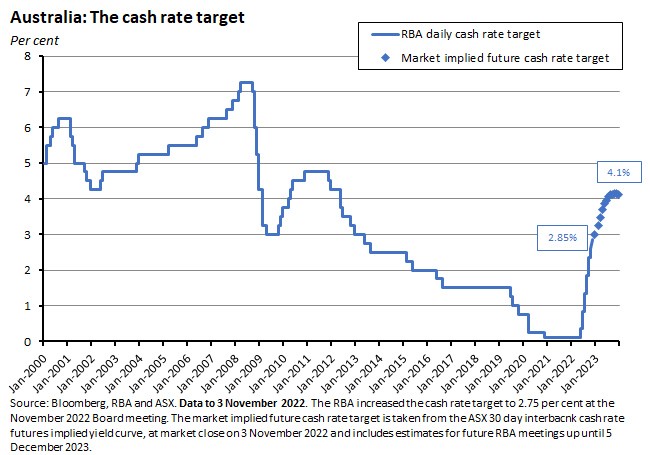

At its penultimate meeting of the year, the RBA said it would increase the cash rate target by 25bp to 2.85 per cent, in line with expectations. The central bank also said that it had revised up its inflation forecasts and it now thinks inflation ‘will peak at around eight per cent later this year’. It has also trimmed its outlook for economic growth. After seven consecutive rate increases and a cumulative 275bp of tightening, still more rates hikes are in store: Martin Place ‘expects to increase interest rates further over the period ahead’.

Meanwhile, the tightening in monetary policy that has already been delivered continues to squeeze the housing market: CoreLogic’s national Home Value Index fell for a sixth consecutive month in October, with the index now down six per cent from its COVID-era peak. There were also falls in new lending for housing for a fourth consecutive month as well as a drop in the number of building approvals.

The US Federal Reserve has continued to tighten US and global monetary conditions, delivering a fourth consecutive 75bp rate hike this week. Total US rate increases to date now stand at 375bp with more moves promised, and the US central bank is currently embarked on its most aggressive policy tightening cycle since the 1980s.

RBA cash rate target at 2.85 per cent…and rising

There had been little doubt that the RBA would increase the cash rate target at the 1 November Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board this week. Instead, debate had focused largely on whether policymakers would stick to their guns and deliver a regular-sized 25bp hike, or if the stronger-than-expected Q3:2022 CPI reading would see a return to 50bp supersized moves. In the event, the RBA opted to stick with a 25bp increase, in line with its own previous arguments at the October meeting as well as the considerations set out in last week’s note. That leaves the cash rate target at its highest level since the April 2013 RBA meeting (that had left the cash rate target at three per cent before it was lowered to 2.75 per cent at the May 2013 meeting).

Other than the decision itself, there were two key takeaways from this week’s meeting:

First, the accompanying statement trailed the updated forecasts presented in the November 2022 Statement on Monetary Policy (SOMP), released today. The Reserve Bank expects inflation to peak at 8 per cent in the December quarter, boosted by rising energy costs, but wage rises are only forecast to reach a top rate of 4 per cent by June 2024. If achieved, 8 per cent would be the highest since the first three months of 1990 when it was 8.7 per cent.

While inflation forecasts have been revised up a bit and growth projections down, the RBA still anticipates a relatively soft landing for the Australian economy – if not quite as soft as previously – accompanied by gradual disinflation:

- On price pressures, Tuesday’s statement noted that a ‘further increase in inflation is expected over the months ahead, with inflation now forecast to peak at around eight per cent later this year. Inflation is then expected to decline next year due to the ongoing resolution of global supply-side problems, recent declines in some commodity prices and slower growth in demand…The Bank’s central forecast is for CPI inflation to be around 4.75 per cent over 2023 and a little above three per cent over 2024.’ Those changes represent modest increases to the previous inflation forecasts, which had CPI inflation at around 7.75 per cent in the December quarter of this year and 4.25 per cent over 2023 before easing to three per cent in 2024. They also imply that the RBA thinks that inflation will still be – just – above target by the end of 2024.

- On activity, the ‘central forecast for GDP growth has been revised down a little, with growth of around three per cent expected this year and 1.5 per cent in 20232 and 2024.’ The forecasts in the August SOMP had growth at 3.25 per cent this year and 1.75 per cent for the following two years. The RBA has also tweaked the outlook for unemployment, forecasting that the unemployment rate will ‘remain around its current level over the months ahead, but…increase gradually to a little above four per cent in 2024 as economic growth slows.’

Second, November’s meeting also confirmed that the RBA thinks it will have to continue to tighten monetary policy, with the statement noting that ‘The Board expects to increase interest rates further over the period ahead’. That said, there was one new note of dovishness injected into the commentary this week, in the form of the observation that ‘The Board has increased interest rates materially since May.’ While one interpretation of that shift in tone could be that although we’re not at the end of the current rate cycle, we might perhaps be starting to approach it, any such speculation would need to be balanced against the more sobering news that Martin Place judges that it won’t be back on (inflation) target even by 2024.

Governor Lowe subsequently added a bit more colour to the contents of the statement in a dinner speech in Hobart, in which he returned to the familiar theme of the ‘narrow path’ that the central bank is now negotiating between returning inflation to target while at the same time ‘keeping the economy on an even keel.’ He noted that it ‘is still possible to do this’ but also warned that the bank could be knocked off its path, ‘not least because of developments elsewhere in the world.’ The RBA’s central case is still that the economy stays on track, although growth will slow because of the deterioration in the world economy and the squeeze on household finances here in Australia.

Finally, on the likely size and timing of future moves in the cash rate target, he elaborated that while the RBA continued to anticipate further rate increases, it was also prepared to be flexible in terms of how large they would need to be, and whether a pause might be warranted at some stage:

‘We moved in large half percentage point increments for four months, but at this and the previous meeting, we returned to more standard quarter percentage point increases. The earlier large increases were required to move interest rates quickly away from their pandemic levels to address the rapidly emerging inflation problem. But as interest rates moved back to more normal levels, the Board judged that it is appropriate to move at a slower pace while we assessed the data, the economic outlook and the impact of the rate rises to date. We are conscious that interest rates have been increased by a large amount in a very short period of time and that higher interest rates affect the economy with a lag. If we are to stay on that narrow path, we need to strike the right balance between doing too much and too little.

The Board’s base case remains that interest rates will need to go higher still to bring inflation back to target and our forecasts have been prepared on that basis. We are not on a pre-set path, though. If we need to step up to larger increases again to secure the return of inflation to target, we will do that. Similarly, if the situation requires us to hold steady for a while, we will do that.’

House prices continued to fall in October

The CoreLogic national Home Value Index declined for a sixth consecutive month in October, dropping by 1.2 per cent over the month to be 0.9 per cent lower over the year. The combined capitals index fell 1.1 per cent in monthly terms and dropped 3.1 per cent in annual terms.

Values dropped across all capital cities last month, with the pace of monthly decline ranging from a two per cent fall in Brisbane to a modest 0.2 per cent dip in Perth.

The national index is now down six per cent from its April 2022 peak, although to put that fall in context, the preceding growth from the COVID trough to that peak was 28.6 per cent, so most homeowners will continue to enjoy positive equity.

The rate of decline for the national index has now eased from 1.6 per cent in August to 1.4 per cent in September to 1.2 per cent last month, but CoreLogic warned that it was too early to claim that the worst of the decline phase was over: ongoing increases in the cost of living plus further interest rate increases will put household balance sheets under increased pressure and could see a re-acceleration in the rate of house price falls. More positively, the data provider also noted that the downturn to date has remained ‘orderly’, supported by ‘a below average flow of new listings’ along with ‘tight labour market conditions, an accrual of borrower savings and a larger than normal cohort of fixed interest rate borrowers, who have so far been insulated from the rise in interest rates.’ Still, with many market economists expecting a fall of between 15 and 20 per cent, the housing market downturn looks to have some way to run.

In other housing market-related data this week:

- The RBA reported that housing credit rose 0.5 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in September 2022 to be up 7.3 per cent over the year. Total credit growth in September was 0.7 per cent month-on-month and 9.4 per cent year-on-year.

- The ABS said that new loan commitments for housing fell 8.2 per cent over the month in September this year (seasonally adjusted) and were also down 18.5 per cent in annual terms. Lending for owner occupiers was down 9.3 per cent month-on-month and 19.9 per cent year-on-year while the corresponding declines in lending for investors were six per cent and 15.3 per cent, respectively. In a sign that higher interest rates and falling house prices are having an impact, housing lending has now fallen for four consecutive months. That said, the value of loan commitments in September 2022 was still we above pre-pandemic levels: according to the Bureau, owner-occupier loans were 23 per cent higher than in February 2020 while investor loans were 60 per cent higher.

- In another sign of housing market weakness, the ABS also reported that total dwellings approved fell 5.8 per cent in September 2022 (seasonally adjusted) and were 13 per cent lower than in September 2021. Approvals for private sector houses fell 7.8 per cent over the month and dropped 10.4 per cent over the year, while approvals for private sector dwellings excluding houses declined by 1.8 per cent in monthly terms and by 16.8 per cent in annual terms.

- Australia’s dwelling stock was 10,879,349 at 30 June 2022, according to the ABS. That represented an increase of 146,931 dwellings (1.4 per cent) over the year and 38,535 dwellings (0.4 per cent) over the quarter.

No ‘Fed Pivot’ as the US central bank delivers another outsized 75bp rate hike

The RBA wasn’t the only central bank in action this week. The US Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) announced on 2 November that it would increase the target range for the Fed Funds rate by 75bp to a new range of 3.75 to four per cent. That marked a fourth consecutive 75bp rate hike and means the US Federal Reserve has now delivered a cumulative 375bp of tightening over the current cycle (remember, until this year the last time that the Fed hiked rates by 75bp was all the way in 1994). It also leaves the target at a level last seen in early 2008.

Financial markets had been anticipating another 75bp move, so their attention was concentrated not so much on the increase itself, but rather on the Fed’s messaging around what might come next. In particular, markets had been watching for signs of a ‘Fed pivot’ in the form of a shift to less hawkish policy guidance. Here, the Fed gave with one hand but took back with the other:

- Fed Chair Powell did indicate that the Fed is now approaching the point where it might begin to scale back the size of increases from the current XL 75bp moves to smaller increases (‘At some point…it will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases, as we approach the level of interest rates…sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to our two per cent goal’) and in remarks after announcing this week’s decision he added that the FOMC would consider a smaller hike at December’s meeting (‘That time is coming, and it may come as soon as the next meeting, or the one after that.’) In a discussion familiar to RBA-watchers, Powell explained the shift in terms of the size of the cumulative tightening already delivered and the lags with which monetary policy affects activity and inflation.

- At the same time, Powell also made it clear that this did not mean the Fed was close to concluding its tightening cycle, stressing that further interest rate increases would be forthcoming (‘We anticipate that ongoing increases…will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to two per cent over time’). Moreover, he also cautioned that the peak policy rate was still some way off and likely higher than the Fed had expected it to be at the time of the September meeting (‘we still have some ways to go, and incoming data since our last meeting suggests that the ultimate level of interest rates will be higher than expected’).

As a result, while the initial market reaction to the FOMC statement was a brief surge of hope at the prospect of a more gradual pace of policy tightening, that was quickly followed by trepidation that the so-called ‘terminal rate’ – the peak policy rate – had increased. After the September FOMC meeting, Fed officials had indicated via their ‘dot plots’ that the terminal rate was likely around 4.6 per cent. Following Powell’s remarks this week, markets now think it will be around five per cent.

If realised, a higher terminal rate, albeit one that is reached by a more gradual process, implies an increased risk of a US recession. The Fed Chair also seemed to acknowledge that prospect in his remarks, saying that the much-cited ‘narrow path’ between inflation and recession had now ‘narrowed’ further, remarking that ‘no one knows if there’s going to be a recession or not.’

Listen here also to the latest episode of The Dismal Science podcast.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 1.5 per cent in the week ending 30 October, taking the index down to 79.9 and deeper into pessimistic territory. This was the fifth consecutive weekly drop and pushes confidence down to levels last seen during the early weeks of COVID-19 lockdowns. ANZ noted that the share of people who think they are financially worse off than the same time last year has now risen to 47 per cent, the highest value for that indicator in more than three decades. The past six weeks have also seen a 15.6 per cent decline in confidence among people paying off their mortgages. At the same time, Weekly Inflation Expectations surged by half a percentage point to 6.6 per cent last week, the highest reading since February 2011.

The ABS said that retail trade rose 0.6 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in September 2022 to be 17.9 per cent higher than in September 2021. September’s increase in turnover marked a ninth consecutive rise and according to the Bureau was again driven by the combined strength of the food industries, with food retailing up one per cent and cafes, restaurants, and takeaway food services up 1.3 per cent. Every state bar South Australia recorded a rise in turnover in September and turnover is now at record levels across most states. As a reminder, however, these figures are in nominal terms, and therefore include the impact of the high rate of inflation, making it difficult to tell whether the volume of spending is responding to softer consumer sentiment readings and higher interest rates. The ABS also published data on real (inflation-adjusted) quarterly retail sales today. Australian retail sales volumes rose 0.2 per cent in the September quarter 2022, the fourth consecutive rise in quarterly retail volumes, but the smallest since COVID-19 lockdowns ended in October 2021.

The latest ABS Living Cost Indices (LCIs) for the September quarter of this year are now available. The Employee LCI rose 6.7 per cent in annual terms while the Age Pensioner LCI was up 6.5 per cent, for example. Those results compare to the annual rate of increase of the CPI of 7.3 per cent for the same quarter. The growth in annual living costs in the September quarter were the largest seen across all household types since the ABS started producing the series (in 1999 in most cases). In quarter-on-quarter terms, however, the increase in all of the five ABS LCIs was either equal to or faster than the 1.8 per cent quarterly rise in the CPI in Q3:2022. The largest quarterly increase was for employees, with the Employee LCI up 2.6 per cent over the quarter – the largest quarterly increase in employee households’ living costs since the introduction of the GST in the September Quarter 2000. According to the Bureau, employee households were particularly impacted by increases in mortgage interest charges*, which jumped by 24.2 per over the quarter and rose 25.3 per cent over the year. Higher prices for food, automotive fuel and utilities also drove up the LCIs. *The LCIs include changes in mortgage interest charges, which are excluded from the CPI, but exclude changes in prices for new dwellings, which are included in the CPI.

Australia ran a trade surplus of $12.4 billion in September 2022 (seasonally adjusted), up by $3.8 billion from the August result. The ABS reported that exports of goods and services rose by almost $4 billion over the month (seven per cent) while imports edged up by just $0.2 billion (0.4 per cent). The surplus was much larger than the market consensus forecast of $8.8 billion, with exports boosted by higher receipts from iron ore and gas. The more subdued import growth reflected a drop in imports of consumption goods, including a fall in the value of imports of passenger cars. On the services account, Australia’s re-opened borders were reflected in stronger travel exports and imports.

The RBA said that preliminary estimates for its commodity price index showed that the index had fallen two per cent in SDR terms in October 2022 after having edged down by a revised 0.9 per cent in September. The index was still up 22.4 per cent over the year, reflecting higher LNG, coking coal and thermal coal prices. In Australian dollar terms the index rose two per cent over the month to be 28.9 per cent higher over the year.

ABS figures on Australia’s foreign currency exposure as of the March quarter this year.

Updated numbers from the ABS on regional population show that people living in Australia’s capital cities rose by 2.5 million (17 per cent) between 2011 and 2021 while the population of regional Australia grew by 832,000 (11 per cent).

Last Friday, the ABS published the Australian System of National Accounts for the 2021-22 financial year. According to the Bureau, the Australian economy grew 3.6 per cent in volume terms last year, while real GDP per capita rose 3.1 per cent. Labour productivity (GDP per hours worked) rose 1.1 per cent and real unit labour costs fell 0.4 per cent. In nominal terms, GDP rose 11 per cent.

Also from last Friday, the latest ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey shows fewer households reporting impacts on their working arrangements, school or childcare attendance due to COVID-19, with just 13 per cent of households reporting job situation changes due to COVID-19 in September compared to 21 per cent in August. The Bureau says that monthly reporting of this survey will now be paused although collection will remain active.

Other things to note . . .

- Budget 2022-23 Snapshot from the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO).

- The November 2022 RBA chart pack.

- An article from the ABS on the impact of COVID-19 on medical and associated imports (vaccines, PPEs and test kits).

- One assessment from ANU of the distributional consequences of the budget.

- Rodd Sims proposes some regulatory solutions for Australia’s expensive East Coast gas.

- Productivity Commission report on Aged Care Employment.

- Australia’s petrol price cycle.

- A WSJ piece on how the economic outlook is being shaped by a shift from global economic cooperation to discord and conflict. Also from the WSJ, Greg IP considers the fiscal theory of the price level.

- The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2022.

- The OECD’s International Migration Outlook 2022.

- The IMF warns on deteriorating market liquidity leading to increased financial stability risk.

- Also from the IMF, a policy paper on How to cut Methane Emissions.

- The Peterson Institute looks at the data on US-China trade decoupling.

- An Economist magazine briefing on Bidenomics – according to the magazine, an attempt to deliver the biggest overhaul of the US economy in decades by transforming the American economic model.

- Paul Krugman defends the winners of the 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences against criticism that they were doing little more than explaining the obvious, and sets out the simple economics of panic.

- The post-GFC collapse in real interest rates probably wasn’t temporary.

- The FT’s Martin Wolf worries that geopolitical tensions could destroy globalisation. Ray Dalio LinkedIn post arguing that the world order is approaching the ‘war stage’.

- Matt Levine runs through the Crypto Story.

- An Odd Lots podcast covering the US vs China contest over semiconductors. (It prompted me to order the book – yet another to add to pending pile.)

- An earlier offering from the same Odd Lots podcast series – an interview with Nouriel Roubini on the risk of crisis for the world economy.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content