After a three-week break, the Economic Weekly is back from holidays. While we were away, the RBA Board met and left the cash rate on hold for a sixth consecutive meeting, Australia’s central bank released updated economic forecasts as part of the August 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy, and a divide emerged between financial markets and Martin Place over the future trajectory of the cash rate. With the global monetary cycle having turned, markets currently anticipate a rate cut before the year is out. But the RBA is sounding much more cautious, signalling that it thinks policy easing remains some way off – while also insisting, not altogether convincingly, that this messaging does not involve a return to forward guidance. We recap these developments in more detail below, along with a review of recent labour market releases.

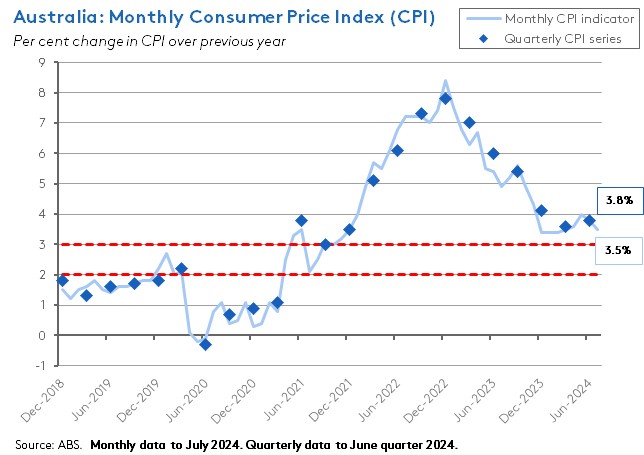

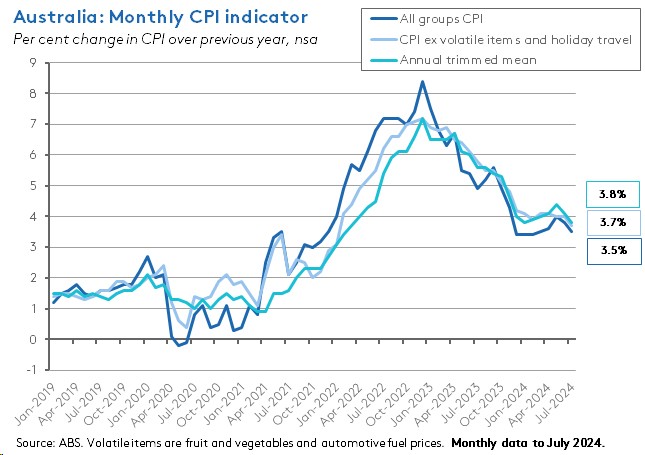

Meanwhile, this week brought another update on progress with disinflation. The Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator for July 2024 reported a fall in the headline rate of inflation, as well as some moderation in underlying inflationary pressures. The former was in large part the product of the temporary impact of Commonwealth and State electricity price rebates, which saw electricity prices drop by more than five per cent over the year to July.

Divergence between the headline and underlying rates of inflation due to government policy interventions to deliver cost-of-living relief is set to be a key theme for the second half of this year and into 2025. In this context, it is useful to remember that while the RBA’s inflation target is based on the headline rate of inflation, the central bank will be paying more attention to the underlying rate when deciding whether or not to adjust the cash rate target, as this provides the superior measure of current price pressures and as such is also more likely to include useful information about the likely future path of inflation.

More on the Monthly CPI indicator below, as well as a roundup of the rest of the week’s data releases and the usual collection of links to interesting reading and listening.

Welcome back!

Monthly CPI indicator up 3.5 per cent over month to July 2024

According to the ABS, the Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) Indicator rose 3.5 per cent over the year to July 2024. That was down from a 3.8 per cent result in June, but a little above the consensus forecast for a 3.4 per cent print.

The Bureau said the most significant contributors to that 3.5 per cent annual increase came from:

- The Housing Group, where the rate of price increase slowed from 5.5 per cent in June to 4 per cent last month. That slowdown was largely driven by a drop in electricity prices, which fell 5.1 per cent over the year to July, following a 7.5 per cent rise in June. The ABS highlighted the impact of new Commonwealth and State rebates, with the first instalments of the 2024-25 Commonwealth Energy Bill Relief Fund rebates starting in Queensland and Western Australia last month, with other State and Territories following this month. There were also State-specific rebates introduced in Western Australia, Queensland and Tasmania. All up, these measures meant electricity prices fell 6.4 per cent over the month. In their absence, prices would instead have risen 0.9 per cent. The Housing Group also saw a modest easing in the annual rate of rent inflation (from 7.1 per cent to 6.1 per cent) and in the growth of new dwelling prices (down from 5.4 per cent to 5 per cent).

- Annual inflation for Food and non-alcoholic beverages rose to 3.8 per cent in July, up from 3.3 per cent in June, reflecting a jump in fruit and vegetable prices, led by prices for strawberries, grapes, broccoli and cucumbers.

- The rate of Alcohol and tobacco inflation rose from 6.9 per cent to 7.2 per cent.

- Annual inflation for Transport fell from 4.2 per cent in June to 3.4 per cent in July, as the rate of automotive fuel inflation slowed from 6.6 per cent to four per cent.

While the drop in the headline rate of inflation was heavily influenced by the temporary impact of federal and state policy interventions, there was also some positive news on underlying inflation. The annual rate of increase in the Monthly CPI Indicator, excluding volatile items and holiday travel, eased to 3.7 per cent in July from four per cent in June, while the monthly measure of Annual Trimmed Mean inflation slowed from 4.1 per cent to 3.8 per cent.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

In the June quarter of this year, total new private capital expenditure (capex) fell 2.2 per cent over the quarter in seasonally adjusted volume terms to be up just 0.3 per cent over the year. According to the ABS, spending on buildings and structures fell 3.8 per cent in quarterly terms and dropped 2.8 per cent in annual terms, while spending on equipment, plant and machinery fell 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter, but was up 3.9 per cent year-on-year. By industry, business investment fell 3.6 per cent over the quarter in the non-mining sector, with this drop partly offset by a 1.5 per cent rise in mining capex. The ABS said the quarterly drop in capex on buildings and structures was driven by lower spending on major engineering and transport infrastructure projects, while the fall in equipment and machinery capex was the product of a decline in retail trade investment. The release also included the final estimate for capex for 2023-24, which showed investment up 10.2 per cent, relative to the previous year in current prices. The third estimate for planned capex for 2024-25 saw an upward revision of 10.3 per cent relative to the second estimate.

The ABS said total construction work done rose 0.1 per cent to $64.9 billion (seasonally adjusted) in the June quarter 2024, up 1.2 per cent from the same quarter last year. Building work done was down 0.3 per cent over the quarter and 1.8 per cent lower over the year, at $33.8 billion. Of that total, residential building was 0.1 per cent lower in quarterly terms and 2.9 per cent down in annual terms at $19.8 billion, while non-residential construction fell by 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter and declined 0.3 per cent year-on-year, to about $14 billion. Engineering construction was up 0.5 per cent over the quarter and 1.2 per cent over the year at $31.1 billion.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 0.4 points to an index reading of 82.6 points for the week ending 25 August 2024. Declines in the economic and financial conditions subindices were partially offset by a rise in the ‘time to buy a major household item’ series. Weekly inflation expectations edged up 0.1 percentage points to 4.8 per cent, coming off the previous week’s two-and-a-half year low.

The ABS said the count of Australian businesses rose 2.8 per cent over the year to 2,662,998 actively trading businesses as at 30 June 2024. The business entry rate was 16.8 per cent, while the exit rate was 14 per cent.

The ABS published updated numbers on Australia’s capital cities and regional population. The median age for capital cities in 2023 was 37 years, lower than the rest of Australia (41.9 years). The youngest capital was Darwin with a median age of 34.6 years, while the oldest was Adelaide (39.2 years). Darwin was the only capital with more males than females.

What happened with the RBA and monetary policy while we were away?

The last major data drop before the Economic Weekly headed off for August holidays was the much-anticipated June quarter 2024 Consumer Price Index (CPI) release. Market attention had focussed on this for some time, after a sequence of disappointingly high readings from the Monthly CPI Indicator suggested the risk of an upside inflation surprise, which would in turn placed pressure on the RBA Board to hike the cash rate at its 5-6 August meeting. In the event, that inflation risk largely failed to materialise, prompting a fairly widespread prediction that the RBA would stay on hold for a sixth consecutive meeting.

As expected, the RBA left rates unchanged on 6 August

The expectation that the Board would once again stay its hand at the August meeting was then further reinforced by a short but sharp bout of financial market turbulence that saw a global share sell-off in response to a combination of weak US jobs data, a rate rise from the Bank of Japan and concerns that AI-related shares had been overhyped.

More generally, evidence that the global monetary policy cycle had turned was growing. The Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank had already started to cut rates back in June and had since been joined by the Bank of England (which delivered its first rate cut in more than four years on 1 August) and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (with a first rate cut on 14 August). Authorities in China have also been easing monetary policy. And the US Federal Reserve is now widely expected to deliver a rate cut at the upcoming September meeting. Spurred on by this global policy shift, Australian financial markets have started to price in what they currently see as the near certainty of a rate cut by year-end and the possibility of policy easing coming even sooner.

As readers will be well aware, although the RBA Board did consider the case for a rate hike at the August meeting, ultimately it decided to leave the cash rate target unchanged at 4.35 per cent in line with expectations. That decision came despite the accompanying statement acknowledging that the recent run of price data was showing that inflation was proving persistent, that underlying inflation had been above the mid-point of the RBA’s target range for 11 consecutive quarters and that the decline in underlying inflation over the previous year had been quite modest.

Outlook more hawkish than market predictions of looming rate cuts

The RBA’s latest assessment of the outlook for inflation and interest rates doesn’t sit particularly comfortably with the current financial market view on the likely forward profile for monetary policy, and it was notable that in the media conference that followed the policy announcement, Governor Bullock stressed that the RBA Board remained ‘concerned about the degree of excess demand in the economy’ and cautioned that ‘a near-term reduction in the cash rate doesn’t align with the Board’s current thinking’. Elaborating on the latter point in response to further questions and after first issuing a cautionary disclaimer stipulating ‘no forward guidance’, the Governor went on to explain:

‘I think what the Board’s feeling is that the market path at the moment is pricing in interest rate reductions by the end of this year. I think the Board’s feeling is that the near term, by the end of the year and the next six months, given what the Board knows at the moment and given what the forecasts are, that that doesn’t align with their thinking about interest rate reductions at the moment.’

She later added:

‘…what I’m trying to tell the markets today is that … probably expectations for interest rate cuts are a little bit ahead of themselves…Having said that, we are data dependent and there’s a number of things, as we mention in the Statement on Monetary Policy, that could result in the economy slowing much more quickly and inflation coming down much more quickly than we expect, and we need to be alert to those and if they come to pass then yes, interest rate cuts would be on the agenda. But at the moment, given what we know at the moment, and the forecasts…the near-term interest rate cuts are not in the agenda.’

This message was subsequently reinforced in the publication of the Minutes of the August RBA Monetary Policy Meeting which reported that:

‘…members noted that several developments over preceding months had supported the view that inflation would be slow to decline… In light of these developments, members assessed that the risk of inflation not returning to target within a reasonable timeframe had increased… [members noted that the RBA’s new August forecasts] were also based on a conditioning assumption, derived from market expectations, that the cash rate would be lowered several times in the coming year, beginning later in 2024. Based on what they knew at the time of the meeting, members agreed that monetary policy would need to be tighter than this implied path, in order to bring inflation sustainably back to target within a reasonable timeframe.’

And again:

‘Members also observed that holding the cash rate target steady at its current level for a longer period than currently implied by market pricing may be sufficient to return inflation to target in a reasonable timeframe, but that the Board will need to reassess this possibility at future meetings…They also agreed that, based on the information available at the time of the meeting, it was unlikely that the cash rate target would be reduced in the short term, and that it was not possible to either rule in or rule out future changes in the cash rate target.’

Readers will also note that there is some tension here between the Governor’s disclaimer (‘no forward guidance’) as well as the caution expressed in the RBA’s own review into any future use of forward guidance. It nevertheless looks quite like a form of calendar-based forward guidance in the (qualified) ruling out of any rate moves before year-end. There is also some tension in the language which simultaneously says that it is unlikely the cash rate will be reduced, while also noting it is not possible to rule out future changes.

What we learned from the August 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy

The hawkish messaging from the RBA is in part based on updated forecasts contained in the August 2024 Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP). There are five important messages to take away from that document.

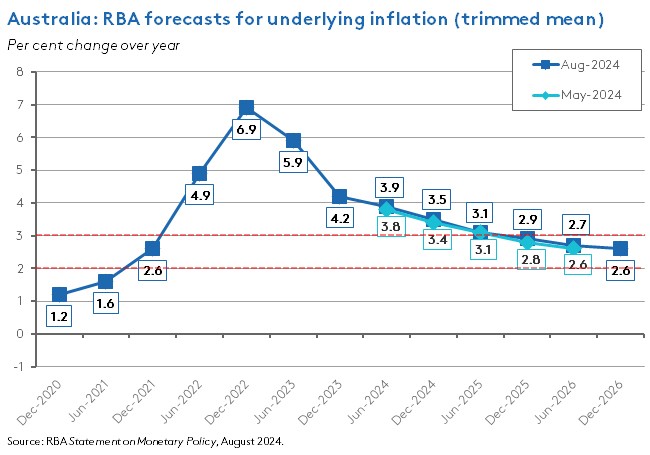

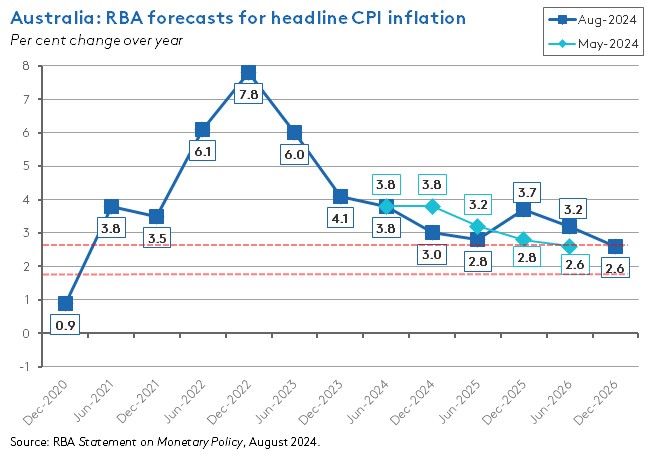

First, the RBA’s new forecasts are slightly more pessimistic in terms of the likely pace of disinflation. Inflation is now expected to take longer to return to target than was projected in the RBA’s May 2024 SMP forecasts, with underlying inflation – as measured by the trimmed mean – now expected to return to target slightly later. It is now projected to be inside the target range by late 2025 and only approaching the midpoint of the range through 2026, reflecting the assumption that the RBA now thinks there will be a little more excess demand in the Australian economy than it did at the time of the March 2024 forecasts (see point three below).

Second, the RBA’s projections for inflation are complicated by a temporary but significant divergence between headline and underlying inflation. The August SMP forecasts the annual headline CPI rate of inflation to fall to three per cent by the end of this year and then ease to 2.8 per cent by mid-2025. That reflects the impact of new and extended electricity rebates from state and federal governments, along with increases to rent assistance, which together are expected to subtract about 0.6 percentage points from annual inflation in the September quarter of this year. Then, however, the legislated unwinding of some of these policies in 2025 (plus an increase in the federal tobacco excise) is anticipated to see the headline rate jump back above three per cent by the end of next year, before it starts falling again through 2026.

The SMP includes a special box on headline and underlying inflation which explains that the divergence between the headline and underlying rates will mainly reflect government policy changes, with the RBA taking the view that ‘they will not materially affect underlying inflationary pressures’, although ‘at the margin’ they might influence inflation expectations. The box also notes that the RBA focuses on underlying inflation when assessing current monetary policy settings.

Third, the modest increase in projections for underlying inflation reflect the RBA’s judgements regarding both the demand and supply sides of the economy. On the demand side, the RBA has upgraded its forecasts for economic growth in 2025, which it says reflects stronger than previously forecast public spending from both federal and state governments, along with a previously anticipated pick-up in household consumption growth. The latter is powered by an increase in real income growth due to the Stage 3 tax cuts, falling inflation and higher household wealth. On the supply side, the SMP’s overall assessment is that conditions in both the labour market and the overall economy are tighter than previously judged. Those revisions mean the RBA now reckons there is more excess demand in the Australian economy than it had estimated back in May 2024.

Fourth, the new forecasts are conditioned on revised market assumptions about the likely trajectory of the cash rate. The August SMP projections for the cash rate follow market pricing at the time the RBA was finalising its forecasts, which had a 25bp cut fully priced in by early 2025 and a fall to around 3.3 per cent by the end of 2026. That is a lower trajectory than the one presented in the May 2024 SMP, which had assumed the cash rate would remain broadly unchanged until mid-2025, before declining to around 3.8 per cent by the middle of 2026. As already noted above, according to the latest Minutes, the RBA thinks current market pricing has it wrong and that monetary policy will ‘need to be tighter than this implied path order to bring inflation sustainably back to target within a reasonable timeframe’.

Finally, the RBA’s forecasts in the August SMP rest on three key judgements and are subject to three key risks. The three judgements are:

- There is more excess demand in the Australian economy and in the labour market than previously assessed.

- Household consumption is at or near a turning point and is now expected to increase in line with its historical response to changes in real incomes and wealth.

- The labour market will continue to ease at a gradual pace before stabilising following a pick-up in GDP growth.

It then follows that the three key risks to the economic outlook as set out in the SMP are:

- There turns out to be even more excess demand in the economy and labour market than currently assessed, meaning the disinflation progress will stall.

- The current period of subdued consumption growth proves to be more persistent than expected, or the recovery in consumption is stronger than forecast.

- The labour market deteriorates by more than expected.

Overall, the RBA judges that risks for activity and inflation are broadly balanced.

What happened in the labour market while we were away?

As that roundup of key assumptions and risks from the August SMP makes clear, the evolution of the Australian labour market over the coming months will have a key influence on the RBA’s thinking. In that context, there were four significant labour market releases over the past three weeks that are worth recapping, with new numbers on employment and unemployment, on wage growth and average weekly earnings, and on job advertisements. Overall, the data paints a mixed picture of the labour market. On the one hand, the evidence does point to an ongoing easing in labour market conditions. The unemployment rate is back up to 4.2 per for the first time since January 2022, the rate of quarterly wage growth has continued to moderate and the number of advertised jobs has now been falling for six consecutive months. On the other hand, overall labour market conditions remain strong. Employment growth was much faster than expected in July this year, while the participation rate rose to a record high, wage growth continues to have a ‘four’ in front of it and to run well-ahead of productivity growth, and while job ads are well down from their peak, they also remain above pre-pandemic levels. In more detail:

First, the ABS Labour Force release for July 2024 reported that the (seasonally adjusted) unemployment rate rose from 4.1 per cent in June to 4.2 per cent last month. That was above the market consensus forecast for an unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent and at 637,000 people, the number of unemployed is now the highest it has been since November 2021, albeit still around 70,000 below pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, the underemployment rate fell 0.1 points from 6.4 per cent to 6.3 per cent over the same period. The net impact was that the combined underutilisation rate edged up from 10.5 per cent in June to 10.6 per cent in July.

According to the same Labour Force release, total employment increased by 58,200 over the month (again, seasonally adjusted) with full-time employment up 60,500 and part-time employment down by 2,300. The overall employment gain was much stronger than the consensus prediction of a 20,000 increase. Other signs of strength in the July data included an increase in the participation ratio to a new record high of 67.1 per cent, along with a rise in the employment to population ratio to 64.3 per cent (just below the record high of 64.4 per cent). Hours worked in July 2024 were also up, increasing by 0.4 per cent or seven million hours over the month.

Second, the Wage Price Index (WPI) for the June quarter of this year showed the seasonally adjusted WPI up 0.8 per cent over the quarter and 4.1 per cent over the year. The headline annual rate was unchanged from the March quarter reading and above the consensus forecast for a four per cent print, but the rate of quarterly increase was below both the consensus forecast for a 0.9 per cent increase and a (revised) 0.9 per rise in Q1:2024. According to the ABS, the private sector WPI rose 4.1 per cent over the year – after three consecutive quarters of 4.2 per cent growth – while the public sector WPI was up 3.9 per cent in annual terms. In terms of quarterly growth, private sector wages were up just 0.7 per cent last quarter, marking the lowest rise for a June quarter since 2021 and the equal lowest quarterly rise overall since the December quarter 2021. In contrast, the 0.9 per cent increase in public sector wages was the highest for any June quarter since 2012, although softer than the 1.3 per cent rise recorded in the December quarter of last year.

About two thirds (67 per cent) of all jobs that recorded a wage change received an annual increase of greater than three per cent. The last time the share was this high was the June quarter 2009. By method of pay setting, jobs covered by individual arrangements contributed more than half of total WPI quarterly growth. By industry, the main contributors to quarterly WPI growth were Professional, scientific and technical services, followed by Construction and Public administration and safety.

Next, the ABS said average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time adults rose 4.6 per cent over the year to $1,923.40 in May 2024 (seasonally adjusted) – a weekly increase of around $85. That was up from 4.5 per cent growth in the year to November 2023. At the same time, the Bureau also noted that average weekly earnings growth over the six months to May 2024 was 1.8 per cent, down from 2.8 per cent over the six months to November 2023.

Finally, the ANZ-Indeed Australian Job Ads index fell three per cent over the month in July, following a downwardly revised 2.7 per cent monthly drop in June. That represented a sixth consecutive monthly decline and means the series has fallen 16.7 per cent since January 2024. The index is now down 28.6 per cent from its November 2022 peak, although it remains 13.3 per cent above pre-pandemic levels. According to ANZ, the share of employers recruiting has fallen sharply. According to Indeed, recent declines in the number of job ads have reflected lower demand in education, food preparation and service and nursing. Over the past three months, Ads have fallen for 57 per cent of occupational categories.

Other things to note . . .

- From earlier this month, the RBA’s August 2024 Chart Pack and Governor Bullock’s Opening Statement to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics.

- Also from the central bank, back on 12 August, RBA Deputy Governor Andrew Hauser gave a speech telling Australians to Beware False Prophets in which he warned of ‘the extraordinary certainty with which individual views about the outlook for the economy and the path of monetary policy can sometimes be expressed….But when the stakes are so high, claiming supreme confidence or certainty over what is an intrinsically uncertain and ambiguous outlook is a dangerous game…It is right to want to be confident that the central bank will bring inflation back to target and maintain full employment. That is the RBA’s mandate, and we should be held to account for it. But the policy strategy required to deliver that outcome and the economic judgements that inform it simply cannot be stated with anything like the same degree of certainty. Those pretending otherwise are false prophets.’ The AFR’s John Kehoe examined the uproar that Hauser’s remarks triggered in some quarters.

- Patterns of progress: The Treasurer’s address for the 2024 Curtin Oration makes the case that the Australian economy is undergoing a fourth sweeping transformation that will be shaped by AI, the expansion of the care economy, the rise of renewable energy and the ongoing economic rise of the Asian region.

- The Grattan Institute warns against rent-seeking and picking winners.

- The ABS on the government’s Measuring What Matters wellbeing framework.

- A Treasury consultation paper on Revitalising National Competition Policy. A Treasury working paper on how competition impacts prices in the Australian aviation sector.

- The Productivity Commission is to examine Australia’s opportunities in the circular economy.

- Materials for the US Fed’s 2024 Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium. The speech from US Fed Chair Powell in particular is worth a look.

- This BIS Bulletin looks back to the global market turbulence earlier this month.

- The 2024 IMF Article IV Report for Indonesia and the accompanying Selected Issues report which analyses Indonesia’s goal of becoming a high income country by 2045.

- A report from the McKinsey Global Institute on Navigating the physical realities of the energy transition.

- Two FT Big Reads. One looks at the likely legacy of the US IRA and Chips Acts. The other examines the sometimes contentious relationship between the IEA and the oil industry.

- Aeon magazine on the great wealth wave.

- Related, housing survey data suggests that within-country inequality is falling.

- A Foreign Affairs essay on China’s real economic crisis.

- In the WSJ, Greg Ip on the year (US) politicians turned their backs on economics.

- The World Bank’s World Development Report 2024 considers the Middle-Income Trap.

- Matt Klein says a strategic bitcoin reserve is an absurd idea.

- What attacks on shipping mean for the global maritime order.

- How should policy respond to low fertility rates and population decline?

- The Economist magazine asks, why do Australians outlive their Anglophone peers?

- The FT’s Unhedged podcast considers the recent surge in the gold price. The Odd Lots podcast examines what a Fed policy easing cycle might look like. The Econtalk podcast discusses complexity economics.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content