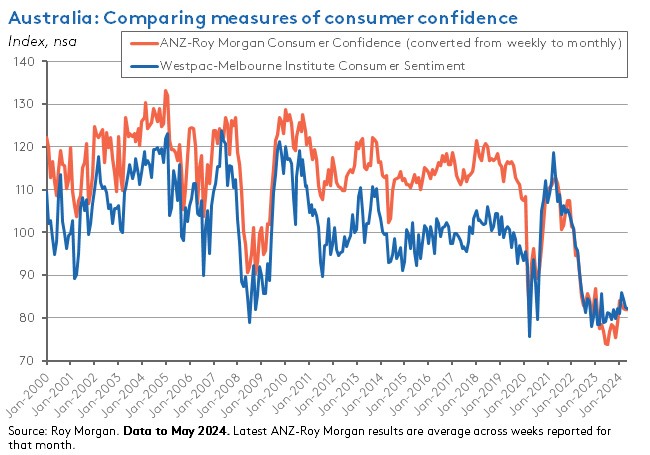

Following two eventful weeks on the economic policy front – first the May RBA Board meeting, then Budget 2024-25 – this one was quieter. The key data download came in the form of new readings on consumer sentiment, with both the monthly Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index and the weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan numbers reporting that confidence levels remain mired at very subdued levels.

There were some indications of a modest positive reception for the Budget, but any lift looks to have been offset by persistent concerns around inflation, interest rates and the cost of living.

This week’s publication of Minutes from the May RBA meeting confirmed that the Board discussed the case for a rate increase earlier this month before opting to leave policy unchanged. Along with providing a helpful summary of the competing arguments facing policymakers, the Minutes explained that ‘members judged that it remained reasonable to look through short-term variation in inflation to avoid excessive fine-tuning.’ That suggests that a bumpy disinflation path on its own will not necessarily trigger a rate response, and that the RBA will require some quite large shifts in the data flow and the associated balance of risks to deliver a future rate move - in any direction. Granted, all else equal, the net fiscal stimulus now set to be delivered by the Budget over the next financial year does represent some upside risk here. But as discussed in my post-budget webinar, the magnitude of new spending outside of the already announced Stage 3 tax cuts is relatively small (and see also the discussion below on surveyed intentions over spending vs saving regarding the latter).

Last week’s data releases on the labour market suggested that nominal wage growth may now have peaked. They also reported increases in the unemployment and underemployment rates in April while at the same time showing still-strong employment growth, albeit running below the rate of population increase. To balance against this evidence of labour market easing, this week’s Flash PMI estimates for May found that business and hiring activity continues to expand, and that cost pressures overall have remained ongoing, with the survey indicating that input prices rose at their fastest rate in six months.

Consumer confidence remains subdued after Budget 2024-25

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index slipped by 0.3 per cent over the month to a reading of 82.2 in May 2024, with Westpac noting that renewed cost-of-living pressures and inflation concerns were large enough to ‘more than offset what looks to have been a relatively well-received Federal Budget’. As a result, consumer sentiment remained stuck at deeply pessimistic levels for yet another month.

Since the May Survey was conducted over budget week, this allowed for pre- and post-Budget comparisons. Sentiment amongst those surveyed pre-budget showed an index read of 86.8 while sentiment of those surveyed after the announcement was 11.8 per cent lower, at 76.6. Note, however, that Westpac reckons that sentiment usually drops by a few percentage points between pre- and post-budget samples as optimistic pre-budget hopes meet post-budget reality. Still, this drop is larger than that, perhaps indicating a greater than usual level of disappointment.

On the other hand, responses to an extra survey question directly on the impact of Budget 2024-25 indicate a more positive response to the Treasurer’s offering: when asked in relation to past budgets, previous version of this question have typically generated a heavy negative bias in the response, with those saying they expected to be worse off outnumbering those expecting to be better off by around 20-25 per cent. In contrast, this year the gap was just three per cent. Except for the big stimulus budgets of the COVID period, Westpac said, this was the least negative response in the past 14 years.

Another budget-related finding of note relates to the Stage 3 tax cuts. Of those respondents who said they expected to receive a tax cut, 30 per cent said they planned to save all of it and a further 50 per cent expected to save at least half. Combining these survey responses across income groups with Treasury’s numbers on the distribution of tax relief, Westpac estimates that Australian households plan to save around 80 per cent of their tax cuts. If that holds, only $4.7 billion of $23.3 billion in tax relief would be spent, producing a spending boost of just 0.35 percentage points. If instead households spent half of their tax cuts, that spending boost would increase to about 0.9 percentage points. Those results suggest that the inflationary impact of the budget’s fiscal relief is likely to be quite limited.

Meanwhile, the ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index rose 1.8 points to an index reading of 82 in the week ending 19 May 2024. That’s consistent with a modest ‘budget boost’. All five subindices rose over the week, with increases in the economic confidence measures outpacing smaller gains in the financial conditions results, although it is worth noting here that the future financial conditions subindex did climb above neutral for the first time in seven weeks. ANZ said that the overall gain was driven by a 3.9-point increase in confidence amongst renters, which it reckoned could be linked to Budget 2024-25 initiatives including the ten per cent lift to Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Despite the weekly increase, however, the weekly confidence index also remains at very low levels, sitting below 85 for a record 68th consecutive week. Meanwhile, weekly inflation expectations remained unchanged at their 2024 low of 4.8 per cent.

RBA Minutes show a central bank weighing up the risks

The RBA published the Minutes of the 6-7 May 2024 Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board. They reported that members debated the case for an increase in the cash rate target vs leaving policy unchanged. The context for that debate has been provided by a sequence of pre-meeting data releases that had indicated:

- Consumer spending had been weaker than expected as households had saved more of their income than the RBA had anticipated.

- Labour market conditions had eased by less than expected. The minutes said that explanation for this resilience in employment growth was unclear, but perhaps reflected some mixture of labour hoarding, less productive marginal workers, strong population growth, the nature of the current mix of demand, and/or diverging spending outlooks between consumers and businesses.

- Inflation data had been stronger than the central bank had expected with both domestic labour and non-labour cost pressures remaining high.

- Overall financial conditions remained restrictive, especially for households where several household financial indicators were consistent with conditions being significantly tighter than the average of the preceding 15 years. Members also noted that the cash rate was above most of the RBA’s estimates of the so-called ‘neutral rate’ – the level consistent with monetary policy being neither expansionary nor contractionary – while conceding that there was a high level of uncertainty around these estimates.

As a result of these changes, the RBA’s May 2024 staff forecasts still had inflation returning to target within the same timeframe as in the February vintage, but this trajectory was now predicated on a technical assumption for the cash rate that was noticeably higher than previously assumed, with market pricing now assuming no reduction in the cash rate until 2025. And in the near term, inflation outcomes were likely to be higher.

In this context, the Board considered two sets of arguments for tightening policy:

- As already noted, the flow of data since the Board’s previous meeting had mostly been stronger than the RBA had expected. If this meant staff forecasts were overly-optimistic about the disinflation process – for example, if benign labour market conditions and a recovery in real household disposable income meant that consumer spending surprised to the upside, alongside further growth in public demand and business investment, leading to demand running above supply for longer – then a higher cash rate could be appropriate.

- Even if demand continued to be relatively weak, other factors could still work to slow the pace of disinflation, warranting a policy adjustment. For example, this might be the case if weakness in trend productivity growth led to a persistent misalignment with wage growth, or if inflationary expectations drifted higher.

- Against this were two sets of arguments for leaving the cash rate target at 4.35 per cent:

- Despite some upside surprises in the data flow since the last meeting, it was arguable that they were not large enough to warrant a change in policy, especially given that inflation was still declining towards target, and that the staff forecasts remained consistent with a credible timetable for disinflation.

- An unchanged cash rate target would also help mitigate the risk that future demand growth turned out to be slower than envisaged in the latest forecasts – for example, if consumer spending remained weaker for longer against the backdrop of a softer labour market. It would also account for ongoing uncertainty around the ‘full employment’ rate of unemployment.

As we know, the Board judged that this second set of arguments was more convincing, with the Minutes noting that members:

‘…agreed that the flow of information since the previous meeting had increased the risks of inflation staying above target for longer. However, members considered that the staff forecasts presented a credible path back to the inflation target, with the risks surrounding the forecasts judged to be balanced. Importantly, inflation expectations remained well anchored. Given this, and the higher-than-usual level of uncertainty about the economic outlook, members judged that it remained reasonable to look through short-term variation in inflation to avoid excessive fine-tuning.’

The comment here about the desire ‘to avoid excessive fine-tuning’ is noteworthy, especially in a context where the Board still judges that it is ‘difficult either to rule in or rule out future changes in the cash rate target’ even though ‘recent data and other information had signalled that the risks around inflation had risen somewhat.’

This messaging would seem to suggest that the hurdle for any future rate change – up or down – remains quite high, and that the most likely outcome is for the RBA to persist with current policy settings for some time yet. All that said, it is worth noting that the Minutes also acknowledged that the RBA’s forecasts ‘did not incorporate any measures that may be announced in the forthcoming federal and state budgets for 2024/25.’ Expect Governor Bullock to be questioned on this point at the next press conference.

From last week: An update on labour market conditions

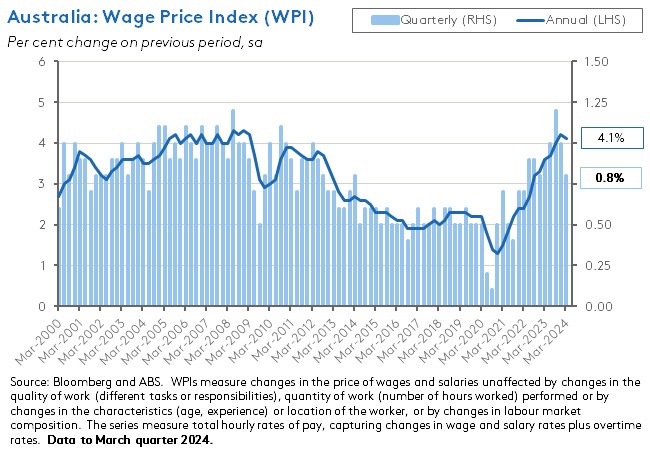

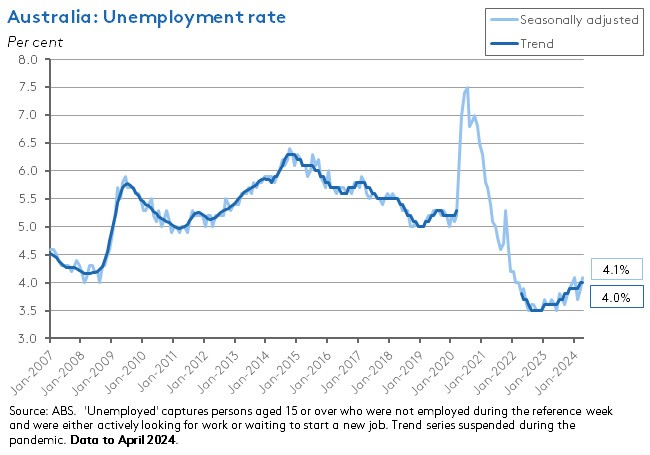

Related to the debate over the pace of disinflation and the future trajectory of monetary policy, two data releases from Budget Week suggested that the Australian labour market is easing, albeit from what still appear to be very tight conditions. There were signs that the rate of nominal wage growth might have peaked while the unemployment rate has now moved back above four per cent.

First, last Wednesday, the ABS released the Wage Price Index (WPI) for the March quarter 2024. The new numbers showed the WPI up 0.8 per cent over the quarter and 4.1 per cent higher over the year. That marked a modest slowdown from the December quarter 2023’s one per cent quarterly and 4.2 per cent annual rates of growth. It also came in softer than market expectations, with the consensus forecast having predicted a 0.9 per cent quarter-on-quarter and a 4.2 per cent year-on-year outcome.

This was also the third consecutive quarter of above four per cent wage growth. In a sign of ongoing labour market pressure, the last time wage growth was sustained at or above four per cent for an extended period was the sequence that came to an end in the March quarter 2009. At the same time, however, the quarterly outcome was the lowest rate of increase recorded since the December quarter 2022.

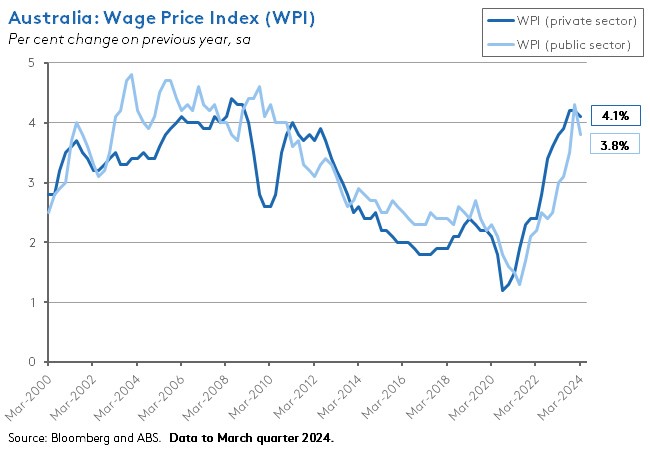

The rate of growth in the private sector WPI slowed from one per cent over the quarter and 4.2 per cent over the year in the December quarter last year to 0.8 per cent over the quarter and 4.1 per cent over the year in the first quarter of this year. In this case, the quarterly growth rate was the slowest recorded since the March quarter 2022.

Public sector WPI growth also moderated, dropping from 1.4 per cent in quarterly terms and 4.3 per cent in annual terms in the December quarter to 0.5 per cent and 3.8 per cent in the March quarter, respectively. Again, the rate of quarterly growth was the lowest the since March quarter 2022. In this case, the Bureau noted that while last year’s March quarter result had seen the implementation of new public sector enterprise agreements and changes to wage gaps, many of the jobs covered by these new agreements saw scheduled pay rise in the September or December quarters of last year instead of the March quarter this year.

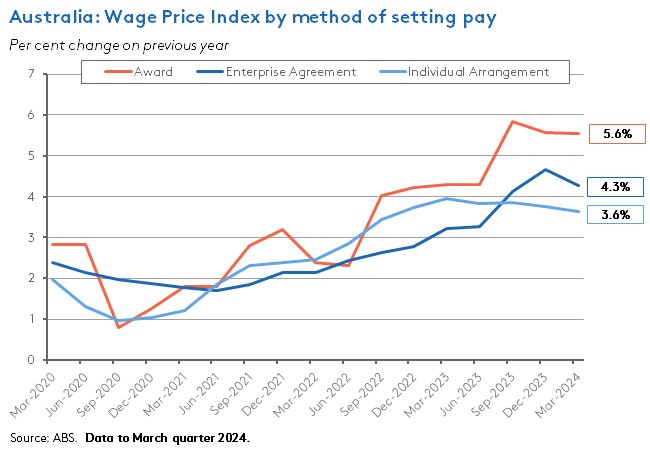

According to the ABS, jobs covered by individual arrangements drove more than half of WPI quarterly growth over Q1:2024, while Enterprise Agreements had a smaller impact, reflecting fewer of the latter in the quarter. The annual rate of increase for wages under individual arrangements – typically viewed as the most responsive to current market conditions – eased from 3.7 per cent in the December quarter of last year to 3.6 per cent in the March quarter of this year.

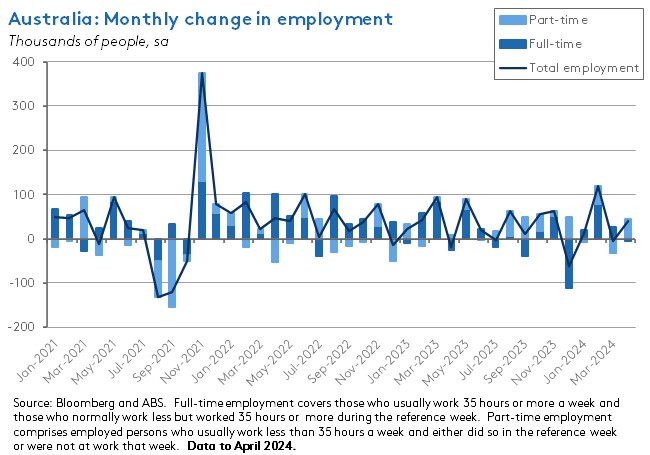

Second, last Thursday the ABS published the Labour Force results for April 2024. The number of unemployed people rose by 30,300 over the month (seasonally adjusted) while the unemployment rate rose by 0.2 percentage points from (an upwardly revised) 3.9 per cent to 4.1 per cent. The underemployment rate also rose by 0.2 percentage points climbing to 6.6 per cent. As a result, the underutilisation rate increased to 10.7 per cent.

This was a weaker outcome than anticipated by market economists, where the median forecast had called for a 3.9 per cent unemployment rate. On a trend basis, the unemployment rate remained at four per cent, unchanged from the previous month.

The ABS said that as well as an increase in the number of people without jobs who were available and looking for work the increase in the number of unemployed also reflected more people than usual indicating that they had a job and were waiting to start.

Employment increased by 38,500 people in April 2024. That comprised an increase of 44,600 in part-time employment that was more than enough to offset a 6,100 drop in full-time employment. The consensus forecast had anticipated a 23,700 increase in the number of people in work, so in contrast to the unemployment reading, the employment reading surprised to the upside.

The participation ratio rose to 66.7 per cent last month while the employment to population ratio held steady at 64 per cent.

Trend employment growth was 30,900 in April, representing about 2.5 per cent annual growth. That means employment growth is currently running below population growth, which the ABS put at around 57,300 last month (that is, an annual growth rate of around 2.9 per cent), consistent with an easing in labour market conditions.

If we adopt Treasury’s medium-term assumptions about labour market equilibrium in the Australian economy, they imply that a sustainable environment would involve an unemployment rate of around 4.25 per cent, annual nominal wage growth of about 3.75 per cent and annual labour productivity growth of around 1.2 per cent. We can contrast that with current conditions: an unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent, wage growth of 4.1 per cent, and labour productivity growth of -0.4 per cent (the latter based on the Q4:2023 national accounts). Judged on that basis, conditions are on their way back to more sustainable levels but are not there yet. The glaring exception here is labour productivity growth, which was still going backwards in annual terms late last year (although note that quarterly growth had turned around, and if the ‘productivity bubble’ hypothesis is correct, we should see a return to annual growth over the course of this year).

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The Judo Bank Flash Australia Composite PMI Output Index (pdf) slipped to 52.6 in May 2024 from a reading of 53 in April. While that marks a three-month low, it also leaves the PMI in positive territory for a fourth consecutive month, indicating an ongoing expansion in private sector activity and continued business resilience, despite the very weak consumer confidence numbers reported above. The Flash Australia Services PMI Business Activity eased to 53.1 in May (another three-month low) from 53.6 in April while the Flash Australia Manufacturing PMI Output Index rose to 48.9 – an eight-month high, albeit one that still signalled continued contraction, if at a slowing rate. Overall, incoming new business rose at the fastest rate since June 2022 and employment growth was also positive, with the reported rate of increase in headcount the fastest in eight months. At the same time, the PMI survey results show input prices rising at their fastest clip in six months with higher raw material and transport costs reported in both the services and manufacturing sectors and higher labour costs in the former. Businesses passed on some of these cost increases to customers, leading to higher output price inflation rates.

The ABS Monthly Employee Earnings Indicator for March 2024 reported that total wages and salaries paid by employers rose to $99.5 billion (calendar-adjusted, original series). That was up 2.1 per cent over the month and 7.1 per cent over the year. Note that the ABS describes this this data release as an experimental estimate.

The ABS said that there were 4.2 million retirees in Australia in the 2022-23 financial year. The average age at retirement of all retirees was 56.9 years, the average age of the 130,000 people who retired in 2022 was 64.8 years, and the average age people intend to retire is 65.4 years. The Bureau noted that while the average intended retirement age has been steady at between 65 and 65.6 years since 2014-15, the actual retirement age has risen over this period, climbing from 58.5 years in 2014-15.

Other things to note . . .

- The Parliamentary Budget Office’s suite of products on Budget 2024-25: a budget guide (pdf), a budget snapshot, and historical fiscal data.

- In the AFR, Jonathan Kearns on budgeting for bad times.

- Treasury’s advice on the Future Made in Australia agenda.

- A new Productivity Commission research paper provides an update on the state of economic inequality in Australia, reviewing the period including the COVID-19 recession and recovery. The authors find that the initial pandemic period brought an unprecedented decline in income inequality due to the surge in government support payments. Wealth inequality also fell across the pandemic period, in part because some lower income households were able to use this government support either to save or to reduce debt (noting that the regional house price boom was also important here). As the economy recovered and government support was phased out, income inequality rose again. The paper also examines economic inequality for three cohorts: women, older people, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- The CSIRO has released the 2023-24 GenCost report, which includes costs for large-scale nuclear technology for the first time. The CSIRO again finds that renewables, including costs associated with additional storage and transmission, remain the lowest cost, new build technology. That’s even though the cost for wind power has been revised up. The report says that nuclear power is more expensive than renewables and would take at least 15 years to develop, including construction time.

- The Australian Government’s Future Gas Strategy.

- Grattan says Australia’s renewables revolution is running late.

- The government’s new National Battery Strategy.

- Sarah Hunter, the RBA’s Assistant Governor (Economic) gave a speech on Housing Market Cycles and Fundamentals. On the demand side of the equation, she emphasised strong population growth due to higher net overseas migration and a decline in the average household size to around 2.5 persons per household (partly due to an aging population and lower birth rates, partly due to pandemic-driven preferences for more living space and the parallel shift to WFH). On the supply side, new supply has yet to pick up in response to the surge in demand, with dwelling completions trending down over the past half decade. Here Hunter points to a ‘perfect storm’ of supply-side constraints including: COVID-related supply chain disruptions interacting with the HomeBuilder program; some capacity constraints – such as a shortage of finishing trades – have persisted beyond those pandemic-related distortions; the sector’s cost base has been pushed up, partly by those supply chain disruptions but also by land costs, approvals processes, infrastructure availability and the time required to complete a project; and the cyclical impact of higher interest rates has also played a role.

- ABC Business asks can Australia survive in an inward-looking world?

- The IMF Article IV report and Selected Issues report for New Zealand.

- A new BIS working paper reviews 60 years of global inflation and finds that global factors are important in explaining local inflation, with those factors including the US dollar index, the US federal funds rate, commodity prices and global supply chains.

- Brad Setser has a new paper out on power and financial interdependence.

- Ten foreign direct investment (FDI) trends and the triple divergence: between trends in FDI and global value chains and trends in GDP and trade; between services and manufacturing; and between China and the rest of the world.

- An FT Explainer on the US tariffs on Chinese clean tech.

- Related, Noah Smith says The Big Tariffs are here.

- On the price of oil.

- The WSJ considers the economic, social and geopolitical consequences of falling global birth rates. And the Economist asks, Can the rich world escape its baby crisis?

- Also from the WSJ, Greg Ip on the new US economic strategy to compete with China: tariffs, security restrictions and technology subsidies.

- The OECD’s Digital Economy Outlook 2024.

- The economics of social media.

- FT Alphaville casts a critical eye over a UK version of Swiftonomics.

- The Australia in the World podcast talks Economic security, made in Australia.

- The These Times podcast analyses Biden’s Car War with China.

- And the Ezra Klein podcast asks, Why didn’t the United States get a Jetsons Future? Or alternatively, what went wrong with economic and technological progress in the 1970s?

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content