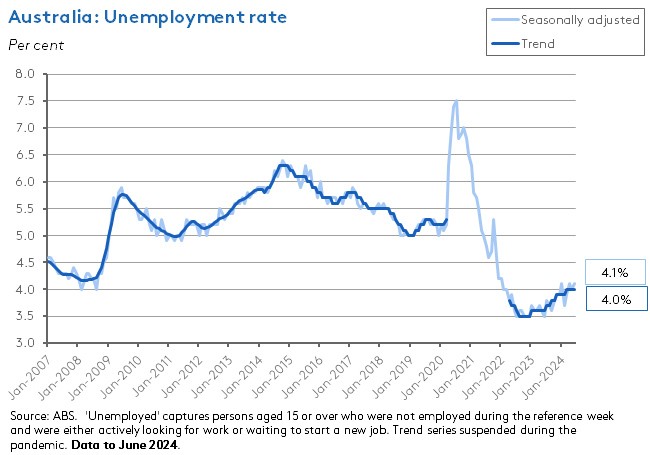

This week’s focus was on the publication of labour force data for June 2024 and what it might mean for the looming RBA Board Meeting on 5 – 6 August. The numbers were a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, they showed the unemployment rate edging back up to 4.1 per cent last month. That result was in line with market expectations and it also meant that the data broadly matched the RBA’s projections for the June quarter unemployment rate. On the other hand, however, employment growth printed much stronger than the median forecast - at more than 50,000, vs a consensus estimate of 20,000.

With the ABS summing up the June data as suggesting that ‘the labour market remains relatively tight’, the immediate financial market reaction was to increase the probability of an RBA rate increase next month (to about 20 per cent at the time of writing). But while it is true that the resilient state of the Australian labour market gives the RBA some room to manoeuvre in terms of scope for further policy tightening, it is also the case that the key data release in terms of any policy decision remains the upcoming June quarter CPI print. That will arrive on 31 July. The RBA’s current forecasts reckon both headline and trimmed mean CPI inflation will run at an annual rate of 3.8 per cent. Results markedly above that – anything that was ‘four point something’ for example – would pose a severe test of the Board’s patience.

As well as a deeper dive into the labour market results, this week’s note also looks at the latest IMF forecasts for the global economy, along with the usual data and linkage roundups.

Employment and unemployment both rise in June 2024

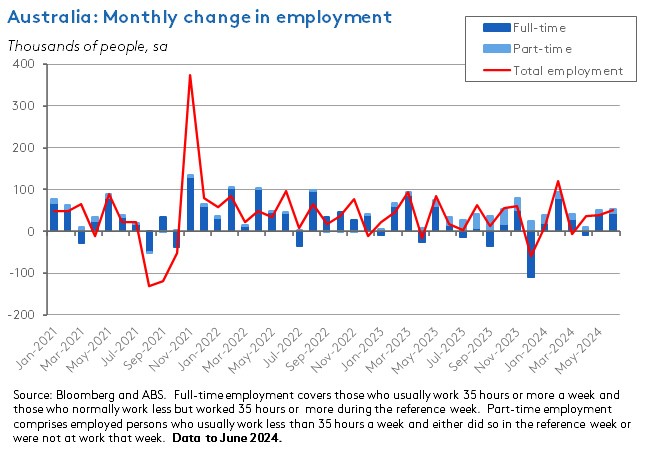

The ABS said the number of employed people in the Australian economy rose by 50,200 (0.3 per cent) over the month in June this year (seasonally adjusted) to be up 2.8 per cent over the year. Full-time employment increased by 43,300, while part-time employment rose by 6,800. The gain was significantly stronger than the consensus forecast, which had predicted total employment to grow by around 20,000. That marks a third consecutive month when the employment numbers have come in hotter than the market expected.

Monthly hours worked in all jobs were up 15 million (0.8 per cent) over the month and 1.4 per cent over the year as the ABS reported that fewer people took annual leave in June 2024 (about 12.5 per cent) compared to the pre-pandemic average for June (14.5 per cent).

Despite the growth in employment, the number of unemployed people rose by 9,700 (1.6 per cent) last month to be 18.7 per cent higher than in the corresponding month last year. As a result, the unemployment rate edged up from four per cent in May to 4.1 per cent in June. That modest increase was in line with the consensus forecast. On a trend basis, the unemployment rate held steady at four per cent.

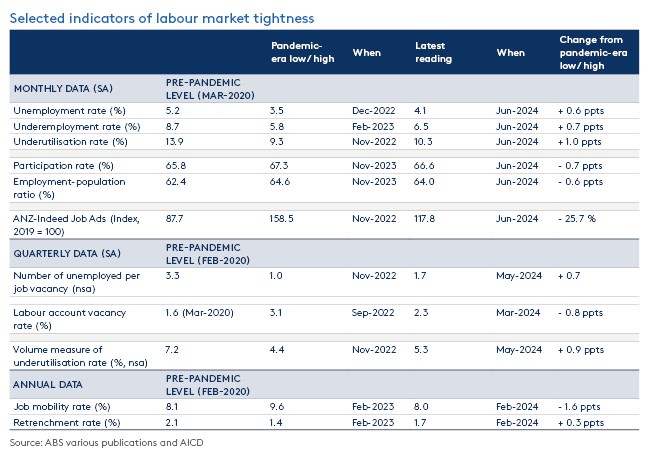

In line with the increase in hours worked noted above, the seasonally adjusted underemployment rate fell 0.3 percentage points, dropping from 6.7 per cent in May to 6.5 per cent in June. As a result, the overall underutilisation rate fell from 10.7 per cent to 10.5 per cent over the same period.

The employment to population rate rose from 64.1 per cent to 64.2 per cent, while the participation rate increased from 66.8 per cent to 66.9 per cent. The latter was just 0.1 percentage points lower than its November 2023 record high of 67 per cent, while the former was 0.2 percentage points lower than its own record high of 64.4 per cent, set in the same month.

The ABS noted that since April 2024 the monthly growth in employment has been running at around 0.3 per cent, which is above the 20-year pre-pandemic average of 0.2 per cent. That means that employment growth has mostly been able to keep pace with Australia’s current period of rapid population growth.

With employment growth surprising strongly to the upside in June, the immediate reaction to this week’s employment numbers has been to suggest that, all else equal, they increase the chances of an RBA rate increase at the upcoming August Board meeting. However, it’s also the case that the latest set of RBA forecasts put the average unemployment rate over the June quarter at four per cent. And that’s pretty much where the numbers have ended up.

Step back a little and take a broader look at the message delivered by the recent run of labour market data and the story continues to be the one that has applied for much of this year. While the labour market is now appreciably looser than it was back in late 2022 when it was at peak pandemic-era tightness, conditions also remain considerably tighter than they were before the onset of COVID-19.

Seen in this context, the June labour market result on its own is unlikely to be enough to push the RBA into delivering a rate hike next month. Instead, and as we have noted several times now, a critical deciding factor for the RBA will be the upcoming June quarter Consumer Price Index (CPI) release, which will be published by the ABS on 31 July.

Update on global economic outlook

The IMF published the July 2024 World Economic Outlook (WEO) Update this week. The Fund’s forecast for global growth in 2024 still stands at 3.2 per cent, unchanged from the April 2024 WEO, while the projection for next year has been nudged up from 3.2 per cent to 3.3 per cent. As IMF Economic Counsellor Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas explains, however, this apparent stability does hide some significant changes below the headline numbers, where there have been adjustments in the distribution of growth across economies and regions. For example, while the Fund now thinks the US economy is demonstrating increasing signs of cooling, it also judges that activity in the Eurozone will pick up after a weak 2023, arguing there is now a degree of convergence in developed economy growth performance following an earlier period of divergence. At the same time, the IMF also reckons Asia’s emerging market economies continue to be the main engine for global growth, with new forecasts for this year including upward revisions to growth for both China (up 0.4 percentage points to five per cent) and India (up 0.2 percentage points to seven per cent) which together now account for almost half of total global growth. At the same time, however, the IMF also argues that medium-term growth prospects for the same region remain soft. In the case of China, for example, it thinks real GDP growth will have slowed to 3.3 per cent by 2029.

Forecasts for activity here in Australia are likewise little changed. The IMF projects real GDP growth to slow from two per cent in 2023 to 1.4 per cent this year (a minor downgrade of just 0.1 percentage points relative to April’s projection for 2024), before predicting growth to then recover to two per cent in 2025 (unchanged from the April forecast).

On the inflation front, the July WEO Update predicts that global inflation will slow to 5.9 per cent this year from 6.7 per cent last year, before easing again to 4.4 per cent in 2025. Once again, those forecasts are little changed from their April 2024 predecessors and keep the world economy on track for a predicted soft landing and a gradual return of inflation towards target(s). But the IMF also warns that the pace of disinflation has slowed in some advanced economies, including in the United States, due to a combination of persistent services inflation and higher commodity prices (although readers should note here that the most recent – that is, June 2024 – US consumer price data showed the annual inflation rate dipping to three per cent, prompting another round of market speculation that the US Federal Reserve could cut rates at the September 2024 FOMC meeting). In this context, the WEO update highlights the presence of some short-term upside risk to inflation outcomes, flagging threats from renewed trade or geopolitical tensions; a potential combination of higher wage growth and weak labour productivity; and the possibility of destabilised inflation expectations. It follows that there is also a consequent risk of ‘higher-for-even-longer’ interest rates, which in turn implies higher external, fiscal, and financial risks.

Global fiscal challenges are also featured on the Fund’s worry list. The post-pandemic deterioration in public finances has not only increased governments’ budgetary vulnerability to future shocks such as higher interest rates but has also made it harder for policymakers to find the funds to tackle pressing spending needs associated with climate change and national and energy security.

Finally, the WEO Update flags the potential for ‘significant swings in economic policy as a result of elections this year’, which it says have ‘increased the uncertainty around the baseline [forecast]’. Those potential policy shifts include the scope for further fiscal profligacy, the prospect of new trade tariffs, and the chances of additional scaling up of national industrial policies.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ABS said total dwelling commencements rose 0.5 per cent to 39,715 dwellings (seasonally adjusted) in the March quarter 2024, down 13.5 per cent on the same quarter last year. The number of commencements for new private sector houses was 25,072, which was up 4.8 per cent over the quarter but down 6.7 per cent over the year. The number of new private sector other residential dwellings fell 3.1 per cent quarter-on-quarter to 14,071, which is 21.5 per cent lower than in the March quarter 2023. According to the same release, the number of new private sector dwellings completed in the March quarter of this year was 41,329. That was down 9.5 per cent in quarterly terms and down 8.1 per cent on an annual basis. Readers will recall that the current federal government’s target is to build 1.2 million new homes by July 2029, implying a construction target of 60,000 dwellings every quarter. Clearly, both current completions and commencements are running well below that figure.

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Index of Consumer Confidence fell 0.5 points to a index reading of 78.5 in the week ending 14 July 2024. This represented the second weakest result since early December last year and means both the headline index (down 36 points) and all the subindices remain well below their pre-COVID averages. ANZ noted that this weakness was particularly evident for the ‘time to buy a major household item’ subindex (down 62 points relative to the 2015-19 average) and the ‘current financial position’ subindex (down 41 points). Net sentiment towards the medium-term outlook for the economy (next five years) has also fallen to its lowest level since November 2023, following the most recent RBA rate increase. Weekly inflation expectations rose 0.2 percentage points to 5.1 per cent.

According to Jobs and Skills Australia, their Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) shows that national online job ads fell 4.2 per cent last month (seasonally adjusted), recording their largest monthly fall since September 2022. Separate survey data also report that recruitment activity softened further in June this year, with a decrease in recruitment activity of eight percentage points over the previous month.

Other things to note . . .

- The July 2024 RBA Bulletin includes articles on assessing potential output and output gaps in Australia, skills matching in the Australian labour market after the pandemic, recent drivers of rising housing loan arrears, and more. There is also a nice explainer providing a helpful overview of the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2020 to 2021.

- The ABS reviews 120 years of population change in Australia. According to the numbers, Australia’s population has increased from 3.8 million in 1901 to 25.7 million in 2021; the national population has grown every year (excluding World War One) since 1901, with the highest net population growth occurring in 2009; annual net overseas migration has increased from 76,000 in 1972 to a pre-pandemic 241,000 in 2019; population growth from net overseas migration has outpaced natural increase since 2006, with the exception of a pandemic-hit 2021; the overseas-born share of the population has risen from 23 per cent in 1901 to 29 per cent in 2021; Australia’s median age has risen from 22.5 to 38.4, the total dependency ratio (the ratio of the combined under-15 and over-65 populations to the 15-64 population has fallen from 0.64 to 0.55 and the old age dependency ratio from seven per cent to 26 per cent, all over the same period; the urban share of the population has risen from 58 per cent in 1911 to 90 per cent in 2021; and fertility has fallen from 3.1 births per woman in 1921 to 1.7 in 2021.

- A submission from the Productivity Commission on the impact of climate risk on insurance premiums and availability.

- A submission from the Grattan Institute on delivering Australia’s green metals opportunity.

- ABC Business outlines the link between monetary policy and the property market.

- The AFR on the battle for Australia’s new submarines.

- Also from the AFR, Raghuram Rajan sets out the range of forces set to drive a future of higher inflation.

- The OECD’s Corporate Tax Statistics 2024 reports that statutory corporate income tax rates remained relatively stable between 2021 and 2024, arresting what had been a long-term decline over the previous two decades, although effective average tax rates have continued to decline at a modest rate. The OECD says the data continue to point to the existence of base erosion and profit shifting, although it also reckons there are signs of modest reductions in these trends in recent years. The publication also provides rankings of corporate statutory and effective tax rates that show Australia has some of the highest rates across the OECD. Similarly, company tax receipts are also higher as a share of GDP and as a share of total tax revenues in Australia than in most OECD member economies. (But do keep in mind the usual qualification that simple cross-country comparisons of statutory company tax rates – while relevant for foreign investors – can be misleading given Australia’s dividend imputation system. So, for example, one ‘solution’ to Australia’s high company tax rate would be to abolish dividend imputation and use the savings to slash the headline rate. That would be good news for foreign investors, less so for domestic shareholders attached to their franking credits. To some extent, our high corporate tax rate also reflects the way that in Australia the company tax rate is doing some of the work that might otherwise have been done by a resource rent tax).

- From the FT, Daniel Susskind discusses the messy truth about achieving economic growth and highlights two key ideas. First, that in practice we still know remarkably little about what drives growth; but second, to the extent that we do know anything, it seems likely that ‘sustained economic growth comes from relentless technological progress.’

- A look at global transport and supply chains from 1965 to 2000.

- The WSJ on China’s soaring local government debt.

- Torsten Slok with Apollo’s economic outlook for China.

- The Economist magazine analyses the intensifying EV trade war between China and the West and in a different piece argues that Trumponomics probably wouldn’t be as bad as some fear in terms of its likely implications for inflation and interest rates.

- A BCG article on private equity and the new normal in geopolitics and trade.

- The secret life of Lithium.

- The UnHerd podcast investigates what the selection of J D Vance as candidate for Vice President might signal for future US economic and other policies.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content