This week we published our latest Director Sentiment Index (DSI). After the previous three consecutive surveys reported positive sentiment overall, the headline index has now fallen back into negative territory, dragged down by the deteriorating global economic environment.

That same economic environment is also providing an unhelpful backdrop to next week’s budget, which will see Treasurer Jim Chalmers deliver the first budget from a new government since Joe Hockey’s controversial 2014 offering. In recent weeks, the Treasurer has been at pains to downplay expectations – he’s told us to expect ‘A pretty standard bread and butter Budget’ and pledged that ‘It won’t be fancy, it won’t be flashy, it will be responsible, it will be solid, it will put a premium on what's responsible and affordable and sustainable.’ That’s because, given the context of that increasingly turbulent global economy plus a domestic central bank that is still locked into inflation-fighting mode, there’s a premium on caution – the UK’s recent, ill-fated experience with Trussonomics has provided a salutary lesson as to the dangers of excessive experimentation in the current environment. The Budget’s challenge next Tuesday, then, will be to balance those fiscal constraints against the need to deliver on the government’s election promises and lay down some markers about the new government’s longer-term shifts in priorities and approach. The latter also requires that next week’s offering help set the tone for future budgets by sketching out the expected trajectory for economic growth, spending, revenue and debt over the coming years – what the Treasurer has described as the beginning ‘of a big national conversation about…how we fund the things that we value.’

From a near-term macro perspective, a largely boring budget would be a useful accompaniment to a quite non-boring period of monetary policy tightening. In that context, this week delivered some background from the RBA on the decision to surprise markets and opt for a smaller-than-expected 25bp increase in the cash rate target at the October Board meeting. The deterioration in the global economic and financial environment looks to have played an important role in the central bank’s thinking earlier this month. Even so, the RBA still reckons that more rate increases will be required to tame inflation.

The key piece of Australian data published this week was the September 2022 labour force report, which showed the unemployment rate unchanged at 3.5 per cent but also a slowdown in the pace of employment growth.

Next week we’ll send out our usual initial, rapid take on the budget. Also, as usual, there won’t be a regular weekly note, but there will be a short version that covers the September quarter CPI inflation print. And finally, another reminder that we will run an economics webinar (free for members) on 3 November that will look back not just at the October budget but also at some of the key economic lessons from a turbulent year and examine some of the implications for 2023.

According to the AICD’s Director Sentiment Index (DSI), sentiment turned negative in H2:2022

The H2:2022 DSI surveyed 1,475 directors between 15 and 27 September this year (meaning that polling took place after the 1-2 September 2022 jobs summit and the RBA’s 50bp rate hike on 7 September, but before the RBA’s 25bp rate hike on 5 October). The overall index score fell to minus 8.5 from a score of plus 10.8 in the first half of this year, marking the first time that the index has been in negative territory since the second half of 2020, when the index was (a much weaker) minus 37.3.

In large part, the decline in the most recent DSI reflects directors’ sense of a marked deterioration in the international economic environment, a judgement that correlates closely with the warnings that the IMF, the OECD and others have been issuing over recent weeks and months. According to our respondents, the economic outlook for the next 12 months has fallen into negative territory (that is, more participants were pessimistic than optimistic) for every region and country covered – Europe, the United States, China and Asia ex China – except Australia. Back in H1:2022, this had been the case only for Europe, which has now moved even deeper into negative territory and has the lowest net balance, while China has seen the biggest deterioration in outlook relative to the previous survey, with a dramatic 28 percentage point fall in the share of respondents predicting a strong economic outcome.

Directors are more upbeat with regard to Australia, albeit less so than earlier this year. A majority (54 per cent) of respondents judged the current health of the domestic economy to be either somewhat or very strong, down only slightly from the 57 per cent feeling the same way in H1:2022. The 12-month outlook is softer, however, with only 42 per cent of directors believing that the economy will be strong in a year’s time, down from 57 per cent in the previous DSI. Still, that 42 per cent exceeds the 27 per cent who think it will be weak.

Drilling down to the state level, economic assessments range from a high of 74 per cent for the share of directors who think that the health of their Western Australian economy will be strong over the coming year down to a low of 28 per cent who think the same for their state of Victoria.

In our regular question on the top economic challenges facing Australian businesses, labour shortages again secured the top spot, maintaining the same ranking and percentage share (60 per cent) as in the H1:2022 survey. Inflation and rising interest rates were ranked as the second most important challenge (by 49 per cent) followed by supply chain challenges (33 per cent) and global economic uncertainty (28 per cent).

Echoing this result, skills shortages were also identified as the top short-term policy priority for the government by 43 per cent of respondents, ahead of climate change (33 per cent) and energy policy (26 per cent). Labour shortages were classed as the second most important issue keeping directors awake at night, behind only cyber-crime and data security, and 83 per cent of directors agreed with the statement that skilled migration levels were not keeping up with labour demand in Australia and would impact growth, while 75 per cent said their organisation had been affected by labour market issues.

Turning to interest rates and inflation, a slim majority of directors (51 per cent) agreed with the proposition that the RBA was increasing interest rates at the right place to combat inflation, although 28 per cent disagreed. Directors did think that this monetary policy response was likely to incur costs, however: 46 per cent agreed that continuing to increase rates at the current pace would cause a recession (noting that the RBA did slow the rate of increase in the meeting following the DSI polling, to 25bp from 50bp), while 52 per cent expected a major uptick in business insolvency rates and 62 per cent anticipated a housing or mortgage crisis in the event of further interest rate hikes.

Staying with the theme of inflation, the latest DSI does not appear to indicate a significant risk of an imminent wage-price spiral, but rather tells a story of more moderate wage growth. When asked about wage levels over the next 12 months, only 16 per cent forecast a strong increase as opposed to the 65 per cent that expected a slight increase. In contrast, 44 per cent anticipated a strong increase in raw material and energy costs, compared to 47 per cent predicting a slight increase.

With the federal budget due next week, it’s interesting to note that government debt levels did not make the list of the top ten economic challenges currently facing Australian businesses (it was ranked #11), while the budget deficit only just made it into the top ten (in tenth place on both rankings) as one the priority issues that the federal government should address in the short term and in the longer term. Directors continue to nominate state-based taxes such as payroll tax as their top priority for tax reform, following by personal income tax and company tax.

One last noteworthy result: while geopolitical risk in general wasn’t ranked particularly highly by directors (although 20 per cent did cite global political conditions as an issue keeping them awake at night), nevertheless 60 per cent of respondents thought it was likely that economic conditions in Australia over the next 12 months would be impacted due to a military conflict or other significant adverse development involving China and Taiwan.

For more on the DSI, which also includes questions on climate change and climate governance, cyber, national reconciliation, and trust in state and federal government, the DSI Insights Report (pdf) is available for download. Sincere thanks to all those readers who were able to participate this time.

Previewing next week’s federal Budget

In a press conference this week, Treasurer Jim Chalmers looked ahead to next week’s budget. The Treasurer stuck largely to the same messages that he has been delivering for several months now, albeit updated after his recent trip to Washington DC.

- He again emphasised the challenging backdrop to the budget, including high and rising inflation but also global geopolitical uncertainty and the impact of natural disasters here in Australia. With regard to the latter, he said it was too early to estimate the likely fiscal fallout from events on the East Coast but noted that there would be an impact on the cost of living and on the budget.

- The Treasurer returned to his now-familiar message on the fiscal challenges created by ‘the big five spending pressures’ facing the budget: aged care, the NDIS, health care, and defence, along with rising debt service costs due to higher interest rates.

- And he highlighted the worsening prospects for world growth, which he said had now seen the Treasury downgrade its forecasts for growth in Australia’s major trading partners. Projected US growth next year has been cut from 2.5 per cent to just one percent, UK growth has been downgraded from two per cent to 0.25 per cent, and Eurozone growth lowered from 2.25 per cent to 0.5 per cent.

Given this context, Chalmers argued that the ‘the key take out is that this is a time for restraint and resilience and that’s what the budget will be about.’ In terms of the likely content, the messaging was again based on the same three aspects that the Treasurer has highlighted in previous press conferences this year. First, that the budget ‘will be focused on responsible cost of living relief with an economic dividend’ that will not push up inflation. Second, that ‘it will have targeted investments in a stronger and more resilient economy.’ And third, that ‘it will begin to unwind the legacy of wasteful spending’. Summing up, Chalmers concluded his press conference by saying:

‘One of the reasons why we decided to do a Budget in October and not to wait between March and May, 14 months, is because I think …this is about implementing our election commitments. It's about giving a more realistic picture of the fiscal situation, not just the size of the challenge that we confront, but the shape of the challenge that we confront over the next four years and over the next 10 years. And it will provide, I think, a baseline for a conversation about the future of the budget.’

There is no doubt that the Treasurer is correct when he draws attention to the fragile state of the global economic backdrop to the budget, and the uncertainty that this generates for the outlook.

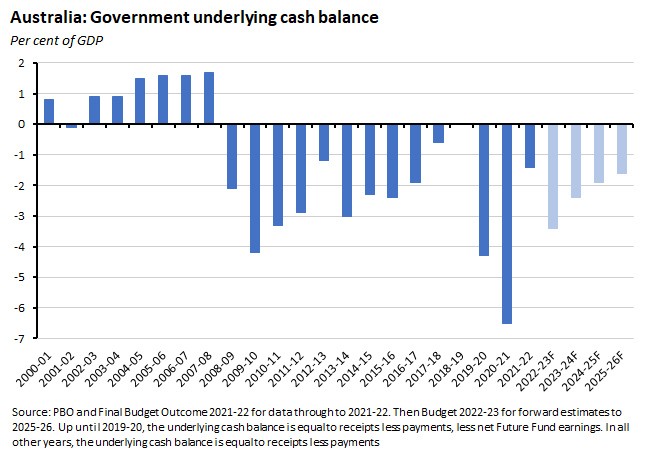

Still, it’s also worth remember that, in the short term at least, some aspects of the fiscal backdrop are looking a lot better than was the case at the time of Treasurer Frydenberg’s March 2022 budget speech. As we noted in our review of the Final Budget Outcome for 2021-22 (pdf), the previous government’s budget had originally predicted an underlying cash deficit for 2021-22 of $79.8 billion or about 3.5 per cent of GDP. The actual outcome was a much smaller shortfall of $32 billion or just 1.4 per cent of GDP – a substantial upside surprise of $47.9 billion that was the joint product of receipts being $27.7 billion higher than anticipated (of which $24.1 billion reflected higher total tax receipts) and payments $20.1 billion lower. Receipts were boosted by a combination of higher company tax receipts due to higher commodity prices and lower than anticipated use of COVID-19 support measures and higher income tax receipts thanks to higher employment. Expenditures were lower due to a range of reasons, including some significant underspends on COVID-19 programs and infrastructure projects: note, however, that when the current Minister for Finance presented the Final Budget Outcome, she said that the government expected that about $10 billion of those underspends would flow through into this fiscal year.

The budget bottom line this year should again benefit from better circumstances than foreseen back in March. Although a cooling global economy means that the outlook for commodity prices overall has dimmed, war in Ukraine has continued to support energy prices. Meanwhile, employment has remained high, inflation has increased, and overall nominal income growth has stayed healthy. All of which suggests that there is scope for additional positive surprises on the revenue side of the fiscal accounts next week. Those gains would be unlikely to be sustained through a global downturn, however, so they are likely to be concentrated in the near-term while more distant estimates are set to remain cautious given the downgrades to the global growth outlook announced this week.

What about spending? The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has provided estimates of the budgetary cost of the government’s election commitments – that is, of those commitments that the Treasurer has pledged to implement in next week’s budget. According to the PBO, the items that will have the biggest impact on the underlying cash balance will be the plans for Cheaper Child Care and for Fixing the Aged Care Crisis, which are estimated to have a net cost of $5.1 billion and $2.5 billion respectively over the forward estimates (to 2025-26). Other substantial commitments over the same time frame include $0.8 billion for Fee-Free TAFE, $0.5 billion for more university places, $0.7 billion for cutting the PBS general co-payment, and about $1 billion in total for strengthening Medicare Fund and Medicare GP Grants.

Set against this, the PBO reckons that the plans to extend and boost existing Australian Tax Office programs and the Plan to ensure Multinationals Pay their Fair Share of Tax will improve the underlying cash balance by $3.1 billion and $1.9 billion respectively over forward estimates, with a further $3 billion reduction in payments anticipated from the Savings from External Labour measure, which is intended to reduce spending on contractors, consultants and labour hire companies.

All up, the PBO estimates that the net impact of this on the budget bottom line to 2025-26 will be a cumulative increase of about $6.9 billion in the underlying cash deficit. Note that since the election, there have also been new spending commitments announced on top of this figure, including those associated with the outcomes of the Jobs Summit (pdf), pledges of additional support for Ukraine, and commitments around extending paid parental leave.

There are also other election-related spending commitments that won’t directly impact the underlying cash balance, although they will show up in the headline cash balance (and eventually will also influence the interest payments component of the underlying cash balance).* That’s because they rely on balance sheet financing arrangements through increases in loans and equity investments. These include the Powering Australia (Rewiring the Nation) initiative, which the PBO estimates will cost $10.3 billion to 2025-26, the National Reconstruction Fund ($5 billion), Help to Buy ($7.6 billion), and the Housing Australia Future Fund ($10 billion). Once these items are included, the PBO estimates that the net impact of election commitments on the headline cash balance over forward estimates will be around $40.5 billion.

*The underlying cash balance is a cash measure of the budget balance equal to the difference between the government's receipts (from tax collections and other measures) and its payments for operational activities including providing services (such as Medicare) and support (such as the age pension) and net investments in non-financial assets (such as land, buildings, infrastructure, and intangibles) used for the provision of goods and services. The headline cash balance is another cash measure of the budget balance. It too is equal to the government's receipts minus payments for operations and net investment in non-financial assets used in the provision of goods and services plus net investment in financial assets for policy purposes. The last category – net investment in financial assets for policy purposes – is the difference between the two measures. It includes public policy commercial and concessional loans and equity investments.

RBA minutes and Deputy Governor’s speech explain the case for October’s 25bp ‘surprise’

This week brought the publication of the Minutes of the October 2022 Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board. This was the meeting at which the RBA ‘surprised’ markets by delivering a 25bp increase to the target cash rate instead of a widely anticipated fifth consecutive 50bp hike. According to the Minutes, the case for another 50bp move rested on the high, and forecast to be yet higher, inflation rate and the consequent risks to inflationary expectations; the risk that a decision to reduce the size of the rate increase would mean the RBA would be out of step with many of its peers, and that this could ‘prompt an unhelpful reaction in inflation expectations and financial markets, if the community came to question the Board’s resolve to reduce inflation’; and that even after past rate increases, ‘the cash rate was not at an especially high level.’ Interestingly, concerns about the impact of a weaker exchange rate on inflation do not appear to have been concern: earlier in the Minutes, the discussion reports that while the Australian dollar had depreciated against the US dollar, it had appreciated slightly over 2022 on a trade-weighted basis, and that ‘the trade-weighted exchange rate typically has a greater bearing on imported inflation than bilateral rates.’ (Technically, it is the currency in which trade is invoiced that should be more important when it comes to thinking about the pass-through from the exchange rate to inflation via import prices: according to the ABS, in 2020-21, about 53 per cent of Australian merchandise imports were invoiced in US dollars, 32 per cent in Australian dollars, and less than eight per cent in euros).

The arguments for switching to a 25bp move ‘rested on the risks to global and domestic growth, and the potential for inflation to subside quickly.’ There were downside risks to household spending, including through a weakening housing market, a sharp increase in Australian wages was ‘less likely than in other economies’ and international ‘inflationary pressures might ease quickly given that the global outlook had deteriorated.’ In addition, ‘in an uncertain environment, there was an argument to slow the adjustment of policy for a time to assess the effects of the significant increases in interest rates to date and the evolving economic outlook.’ Earlier in the Minutes, the discussion had also noted that ‘financial stability risks had increased over preceding months’, although this was largely a reflection of international developments, as ‘households, firms and banks in Australia had entered what was likely to be a more challenging economic environment in a strong financial position overall.’

As we know, members opted for the smaller rate increase:

‘A smaller increase than that agreed at preceding meetings was warranted given that the cash rate had been increased substantially in a short period of time and the full effect of that increase lay ahead. Members also recognised the benefits of a smaller increase while the incoming data on both the global and domestic economy were assessed.’

In addition, the Board also agreed that the RBA is not finished when it comes to further monetary policy tightening, noting that the central bank’s objectives of returning inflation to target and establishing a more sustainable balance of demand and supply in the Australian economy were ‘likely to require further increases in interest rates over the period ahead.’

The same messages also featured in a speech this week from RBA Deputy Governor Michele Bullock on Policymaking at the Reserve Bank. The Deputy Governor explained that while there ‘was no doubt that a further increase in interest rates was warranted…there was an active discussion both internally and at the Board meeting about the appropriate size of the increase’ with members weighing up the arguments already set out above, including the impact of a sharp deterioration in the international environment. She also said that the difference in the approach taken by the RBA relative to other central banks (which have persisted with larger rate increases) could be explained in part by Australia’s particular economic circumstances but also by the fact that:

‘…the Board meets more frequently than most of our peer central banks. The Reserve Bank Board is making monetary policy decisions 11 times a year so it is discussing regularly the evidence on the economy and has more flexibility on the size and timing of rate increases. This is a particular advantage in uncertain times, as it allows more frequent evaluation of the evidence and recalibration if necessary. It also means that if we increase interest rates at every meeting, we can potentially move much faster than overseas central banks. Or, alternatively, we can achieve a similar rise in interest rates with smaller increments.’

In contrast, the US Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) both have only eight scheduled meetings each year.

Finally, and in line with the message communicated by the Minutes, the Deputy Governor explained that

‘The Board expects to increase interest rates further over coming months.’

So, expect another 25bp increase the cash rate target next month.

The labour market was little changed in September 2022

The ABS said that Australia’s unemployment rate last month was unchanged at 3.5 per cent (seasonally adjusted), despite an 8,800 increase in the number of jobless people. The underemployment rate was also stable at six per cent, although the combined underutilisation rate did edge up by 0.1 percentage point to 9.6 per cent.

Employment in September 2022 rose by just 900 people as an increase of 13,300 in full-time employment was largely offset by a fall of 12,400 in part-time employment.

Markets had been expecting a 3.5 per cent unemployment rate and a 25,000 increase in employment.

Hours worked were little changed, down by just 0.6 million hours (seasonally adjusted) from August, reflecting a combination of a higher than usual number of people taking annual leave in September and a higher than usual number of people working fewer hours because they were sick.

There are two messages from these labour market numbers. First, that the labour market overall remains very tight with a multi-decade low unemployment rate and a relatively high participation rate (66.6 per cent) and employment to population ratio (64.2 per cent). But second, that the pace of job growth has slowed over recent months, indicating that the scope for any further labour market gains may now be limited, and with the strong likelihood instead that a softer economy will start to push up the unemployment rate over the coming year.

What else happened on the Australian data front this week?

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index fell 2.8 per cent last week to an index reading of 82.2, its lowest level since early August. Four of the five confidence subindices declined over the week, with only ‘current economic conditions’ edging higher by 0.6 per cent, albeit after having fallen by a cumulative 10.4 per cent over the previous two weeks. By state, confidence was down in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia but up in Western Australia. Weekly inflation expectations jumped by 0.5 percentage points to six per cent, likely reflecting the combined impact of higher petrol prices and a weaker dollar – both of which also probably contributed to the fall in sentiment.

The ABS said that total dwelling commencements fell 2.7 per cent over the quarter to 48,076 dwellings in the June quarter of this year. That was down 28.9 per cent relative to the number of dwelling units commented in Q2:2021. The fall was largely driven by a decline in private sector other residential building commencements, which were down 3.1 per cent month-on-month and 31.8 per cent year-on-year. New private sector house commencements fell 0.2 per cent over the quarter to be down 27.9 per cent over the year. At the same time, the total number of dwellings under construction reached a record high of 241,926 units in the June quarter, up 0.7 per cent on the March 2022 quarter’s previous record. The main driver here was private sector new houses, which have been hitting record highs since March 2021.

This week on The Dismal Science podcast we preview next week's Budget. Plus, we discuss those latest employment numbers, insights from the Director Sentiment Index and China's delayed GDP data.

Other things to note . . .

- The sixth interim report in the Productivity Commission (PC)’s 5 Year Productivity Inquiry series considers what could deliver a more productive labour market. The PC suggests ‘Shifting Australia’s skilled migration system away from one that relies heavily on restrictive skill shortage lists, and towards a system that better enables employer-sponsored skilled migration’; ‘Improving recognition of qualifications and scope of practice’; and reforming workplace relations, including by further simplifying awards where feasible and upgrading an enterprise bargaining system that ‘remains unnecessarily complex and inefficient.’

- An RBA Freedom of Information (FOI) release on wages, productivity and profits.

- The Parliamentary Budget Office’s Overview of the Budget Process (pdf).

- From the ABS, a look at the changing rate of home ownership by generation.

- The Grattan Institute offers some proposals to improve Australian education outcomes.

- Peter Martin says that Australia needs a serious conversation on taxation and spending.

- Steven Hamilton thinks that a global recession is likely, that Australia will do better than most of the rest of the world, and that a tough couple of years are ahead.

- Michael Spence on secular inflation. Spence argues that although some current inflationary pressures reflect transitory factors such as supply chain disruptions and China’s zero-COVID policies, there are also structural factors in play, including a fall in the remaining underutilised productive capacity available in the world economy, a decline in the elasticity of global supply chains as businesses rebalance cost and resilience, demographic aging, and the arrival of ‘a new era of frequent, severe shocks from climate change, pandemics, war, supply chain blockages, geopolitical tensions, and other sources.’

- Nouriel Roubini is predicting a stagflationary crisis.

- A WSJ survey of US economists finds that, on average, they expect the US to tip into recession next year and the Fed to start cutting rates by the end of 2023.

- Duncan Weldon says that the UK (and the Bank of England) have a credibility problem.

- An FT Big Read on Europe’s energy crisis and the threat of deindustrialisation.

- There was no great stagnation, according to Adam Hunt. He reckons that while we may have seen slowdowns in many areas of economic progress, it’s also possible that standard economic metrics such as GDP are proving to be unusually bad at measuring the output of the sorts of technologies (primarily information technology) now taking the lead in the global economy.

- Bloomberg Businessweek says that, contrary to some early expectations regarding the rise of e-commerce, there is little evidence that the pandemic permanently changed shopping behaviour, at least in the United States.

- This week’s Economist Magazine has a special report on China’s plans to remake the world order. The same edition also includes a special briefing on the global battle for tech supremacy.

- Related, the BlackRock Institute on China’s growth challenges.

- Perhaps global labour markets are not as tight as they appear.

- Tyler Cowen defends Ben Bernanke against the charge he is responsible for the world’s inflation problem.

- The Prince is a new podcast series from the Economist which looks at the rise of Xi Jinping.

Already a member?

Login to view this content