At its meeting this week the RBA acknowledged the strength of Australia’s recovery but decided once again to leave all its major policy settings unchanged and continued to predict no change to the cash rate until ‘2024 at the earliest’, although the central bank did note that it would be ‘monitoring trends in housing borrowing carefully.’ The ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly index of consumer confidence fell following the three-day Brisbane lockdown.

A bumper edition this week, as we cover data from the past week and from before the Easter break.

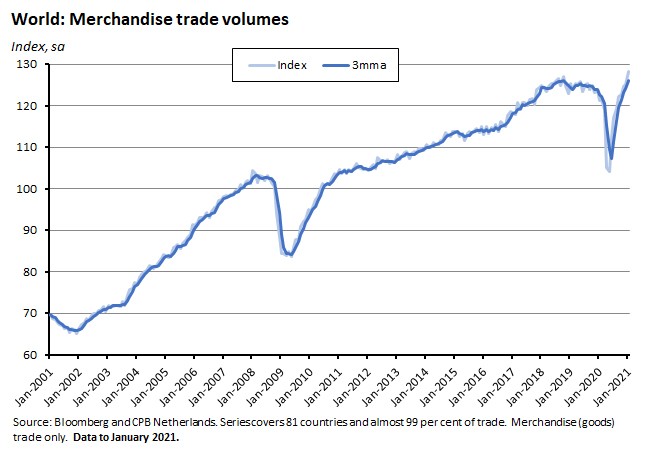

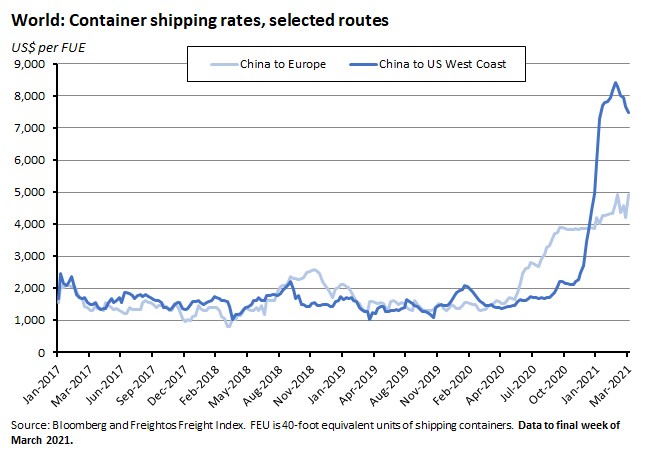

More positive news on the labour market: ANZ Job Ads rose to a 12-year high in March, the ABS said the economy added more than 34,000 job vacancies to the quarter ending February 2021, and payroll job data show that – over a full year of the pandemic – job numbers have recovered to be 0.2 per cent above where they were in the week that Australia recorded its 100th case of COVID-19. The housing market continues to surge as national house prices in March rose at their fastest rate in more than 30 years. New lending for housing dipped slightly over the month in February but was still up more than 48 per cent in annual terms. Growth in housing credit also picked up in February, although net growth was capped by accelerated repayments on existing mortgages. The number of approvals for private sector dwellings hit a new record high in the same month. Higher house prices helped push household wealth up to a record $12 trillion in Q4:2020, following the strongest quarterly rise since Q4:2009. The federal government’s fiscal position is doing better than expected with the year-to-date cash deficit in February more than $23 billion smaller than predicted by MYEFO. Australia’s monthly trade surplus fell to a still substantial $7.5 billion in February. Retail turnover was down 0.8 per cent over the month in February but still up 9.1 per cent in annual terms. ABS data on regional population growth show Brisbane was the fastest-growing capital city in 2019-20. The latest IMF forecasts put expected global real GDP growth at six per cent this year and 4.4 per cent in 2022 after the world economy shrank by 3.3 per cent in 2020. The WTO thinks that world merchandise trade will grow eight per cent in 2021 after contracting by 5.3 per cent in 2020. Merchandise trade volumes are already up six per cent on the same month last year.

This week’s readings include Australia’s economic recovery, our troubled vaccine rollout, an assessment of supply chain vulnerability, new resources and energy forecasts, are we in a housing bubble?, has the RBA failed Australians?, what should we do about China?, Goodhart’s Law, Huawei meets history, and the Archegos affair, as well as podcasts on Australia’s economy after COVID and a look at the pandemic one year on.

And stay up to date on the economic front with our AICD Dismal Science podcast.

What I’ve been following in Australia:

What happened:

At its meeting on 6 April the RBA decided to leave its current monetary policy settings unchanged: the 10bp targets for the cash rate and the yield on the three-year Australian Government bond were left as is, as were the parameters of the Term Funding Facility (TFF) and the central bank’s government bond purchase program.

The accompanying statement noted that Australia’s recovery continues to surprise on the upside, with the unemployment rate dropping below five per cent, the number of employed Australians returning to pre-pandemic levels, and both household and business balance sheets in good shape. Even so, the RBA thinks that – with the exception of a pending temporary rise in the headline rate in the short term – inflationary pressures remain subdued, and ‘underlying inflation is expected to remain below two per cent over the next few years.’

Reflecting the RBA’s confidence in its economic diagnosis, April’s statement stuck almost word-for-word (swapping only ‘is’ for ‘remains’ in the first sentence) with the same concluding paragraph as its March and February predecessors:

‘The Board is committed to maintaining highly supportive monetary conditions until its goals are achieved. The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the two to three per cent target range. For this to occur, wages growth will have to be materially higher than it is currently. This will require significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market. The Board does not expect these conditions to be met until 2024 at the earliest.’

Why it matters:

Not a single RBA-watcher expected a change to the central bank’s policy settings this week, and the RBA duly met those expectations, sticking with the status quo. Likewise, the accompanying message should also be a familiar one by now: the take from Martin Place is that the recovery is surprising on the upside but even so, that still leaves lots of spare capacity in the economy, which in turn means that the prospects for a sustained acceleration in inflation remain low, and therefore no near-term rise in the cash rate is required or even likely. The pace of labour market recovery may well test that analysis at some point, although it’s worth recalling that the impact of the end of JobKeeper has yet to be seen in the data flow.

That assessment also means that the RBA does not see recent activity in the housing market (see stories below on house prices, lending to households and building approvals) as changing the likely forward profile for the cash rate. What the central bank did say on the housing market was that:

‘Housing markets have strengthened further, with prices rising in most markets. Housing credit growth to owner-occupiers has picked up, with strong demand from first-home buyers. In contrast, investor credit growth remains subdued. Given the environment of rising housing prices and low interest rates, the Bank will be monitoring trends in housing borrowing carefully and it is important that lending standards are maintained.’

That is, the focus from Martin Place is on lending standards, and not house prices per se. That fits comfortably with the recent views expressed by APRA’s Wayne Byres (see this week’s readings for a summary of his latest speech). Still, the ‘monitoring trends in housing borrowing carefully’ comment does point to an element of caution. The release of April’s Financial Stability Report later this week is likely to provide further detail on the RBA’s views on the implications of recent developments in the housing market, but at the moment the message is pretty clear: the central bank is viewing housing market developments through the prism of financial stability, and the implication is that macro prudential measures – such as those deployed by regulators in 2015 and 2017 – are likely to be privileged above the cash rate in any policy response.

Finally, this week’s statement also noted that the RBA has still to decide whether it will retain the April 2024 bond as the target bond in its yield curve control (YCC) program or shift to the next maturity. In addition, the RBA’s first $100 billion government bond purchase program or tranche of quantitative easing (QE) is now just about done, the second $100 billion program will start next week, and the statement affirmed that the RBA stands ready to deliver a third package ‘if doing so would assist with progress towards the goals of full employment and inflation.’ Several RBA-watchers have started to tip the RBA announcing such a ‘QE3’ later this year.

What happened:

After rising by 1.4 per cent in week to 27/28 March, the ANZ Roy Morgan Weekly Index of Consumer Confidence slumped 4.1 per cent in the week to 3/4 April.

All five subindices fell over the week: current financial conditions (down a substantial 5.6 per cent), future financial conditions (down 3.4 per cent), current economic conditions (down 3.9 per cent), future economic conditions (down 0.7 per cent) and time to buy a major household item (dropping by 6.6 per cent in the biggest decline since August 2020).

Why it matters:

The key driver of the weekly drop in consumer confidence appears to have been the increase in COVID case numbers and in particular the three-day Brisbane lockdown, with Queensland suffering the biggest fall in sentiment across the states. Confidence was also down in every other state with the exception of South Australia and it is possible that the ending of the JobKeeper program was an additional factor weighing on confidence over the past week.

What happened:

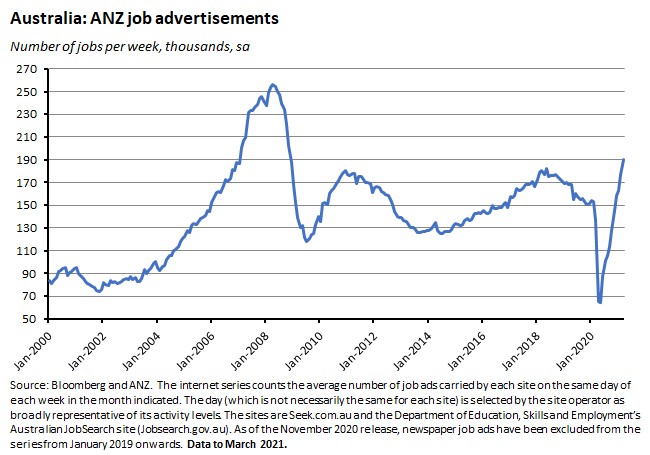

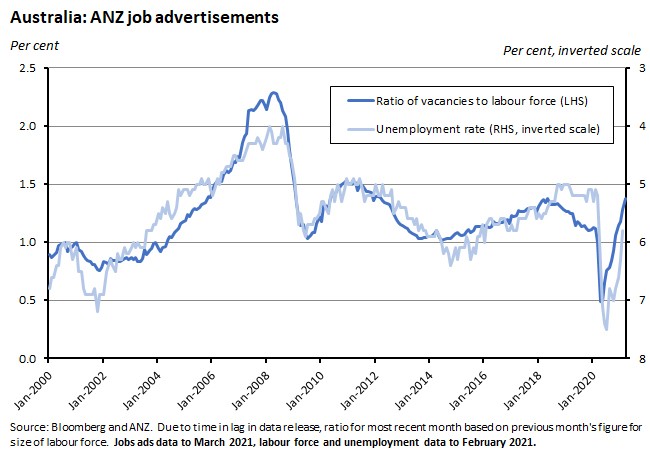

ANZ Australian Job Ads rose 7.4 per cent over the month in March to more than 190,000. That puts the number of ads up nearly 40 per cent over the same month last year.

Why it matters:

Job Ads are now at their highest level since November 2008, suggesting that the labour market recovery remains robust and that the economy overall is looking relatively well-positioned to cope with the impact of last month’s cessation of the JobKeeper program, although that still leaves scope both for a short-term setback in the unemployment numbers and for some significant sectoral effects.

. . . and from before the Easter break . . .

What happened:

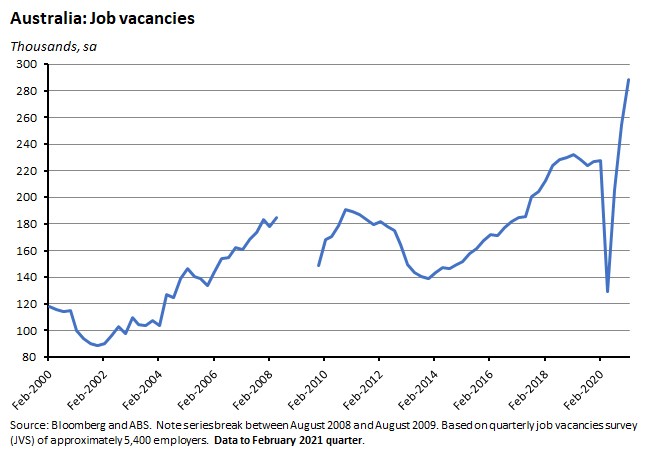

The latest quarterly jobs survey from the ABS for the quarter to February 2021 showed that total job vacancies had risen to 288,700, an increase of 13.7 per cent (or more than 34,000 vacancies) from November 2020.

Private sector vacancies were 260,300, an increase of 14 per cent from November 2020 while public sector vacancies were 28,400, an increase of 11.1 per cent.

By state and territory, there were increases across the quarter and over the year in every geography.

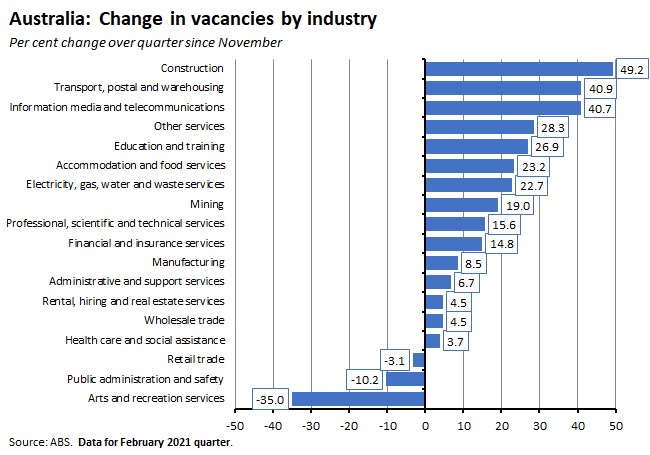

By industry, the biggest increases over the quarter were in construction, transportation and the information, media and telecommunications sectors.

Why it matters:

The large increase in the number of vacancies over the quarter to February this year is another positive indicator of the relative strength of Australia’s labour market recovery. The ABS reported that several industries reported labour shortages, with more than the usual number citing difficulties in filling vacancies for lower paid jobs. This was particularly the case for businesses in the Accommodation and food services industry, where 31 per cent of businesses reported vacancies in February 2021, more than double the 15 per cent share doing so in February 2020.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning here that there are significant differences between the ABS measure of job vacancies and the ANZ measure of job ads discussed above. One difference is that the count of job vacancies includes jobs for which advertisements are undertaken but also includes jobs where other recruitment approaches are used, such as word of mouth (the Bureau notes that according to the National Skills Commission's Survey of Employer's Recruitment Experience, for example, 19 per cent of jobs are not advertised). Another difference is that job vacancies count every position advertised within a single notice, while some job advertisements may be used to fill multiple positions.

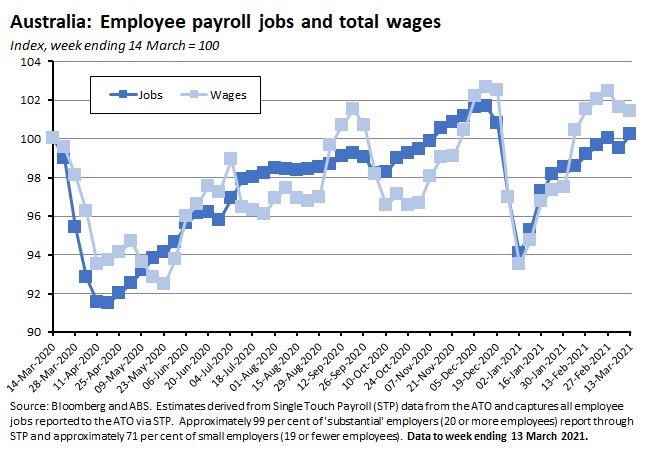

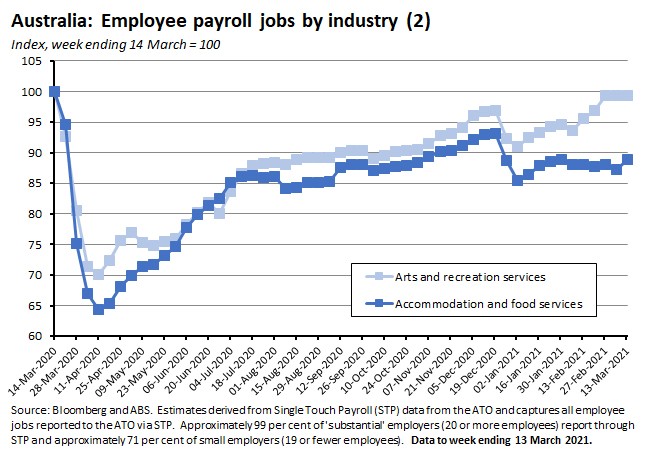

What happened:

The latest weekly payroll jobs and wages numbers showed that between the weeks ending 14 March 2020 (the week in which Australia recorded its 100th COVID-19 case) and 13 March 2021, the number of payroll jobs increased by 0.2 per cent and total wages paid rose by 1.4 per cent. The ABS said that over the most recent fortnight covered by the data, between the weeks ending 27 February and 13 March 2021, payroll jobs increased by 0.2 per cent compared to an increase of 0.9 per cent over the previous fortnight while total wages paid fell by one per cent, compared to an increase of 0.9 per cent in the previous fortnight.

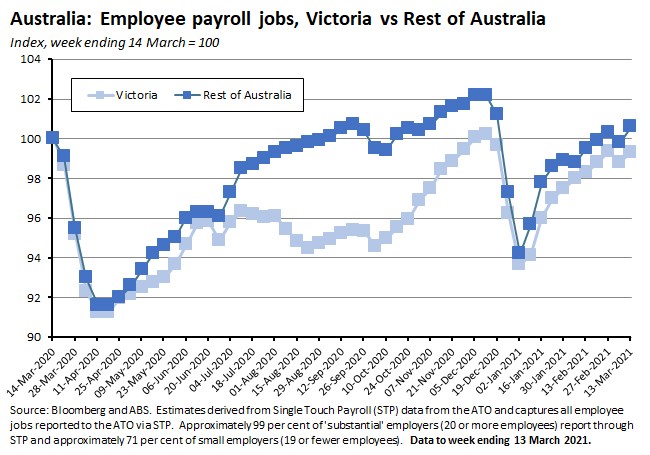

By state, the gain in the number of payroll jobs over the past year has been strongest in the NT (up 3.6 per cent) and Western Australia (up 2.5 per cent) while Victoria (down 0.7 per cent) and Tasmania (down 1.1 per cent) have suffered the largest losses.

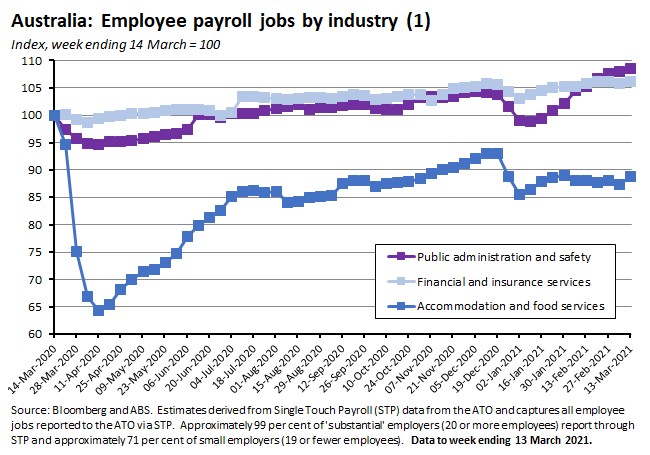

By industry, the biggest payroll job losses over the past year were suffered by accommodation and food services (down more than 11 per cent), information, media and telecommunications services (down 9.2 per cent), and transport, postal and warehousing (down 6.4 per cent). The industries that enjoyed the largest increase in job numbers were public administration and safety services (up 8.6 per cent), financial and insurance services (up 6.2 per cent) and health care and social assistance (up 3.5 per cent).

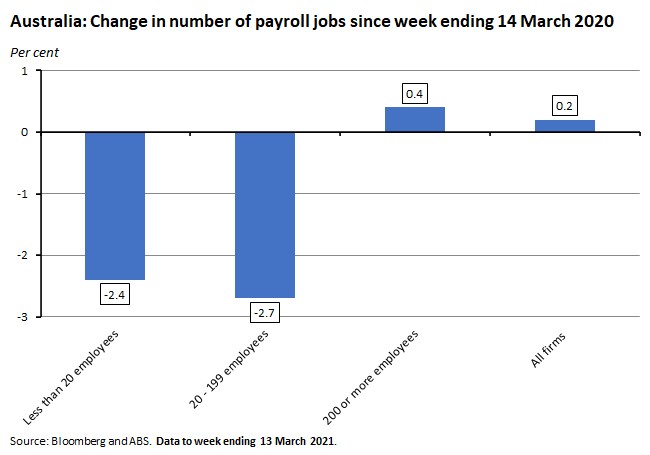

By firm size, job numbers are still down in small and medium sized firms but have (slightly) increased in large firms.

Finally, by demographic profile, the cumulative fall in job numbers over the past year has been greater for men than for women and for younger workers relative to older workers.

Why it matters:

The payroll jobs data now show that – over a full year of the pandemic – job numbers have roughly returned to where they were in the week that Australia recorded its 100th case of COVID-19. The overall national recovery was delayed by the application of a second major lockdown in Victoria, but job numbers in that state are now back up to less than one per cent below their mid-March 2020 levels.

As well as differences by state, the headline results also involve some significant variability across industries. The ABS highlights that one interesting performance gap is between those industries that were only relatively lightly affected by the pandemic in terms of initial job losses (such as financial and insurance services), those that suffered some initial moderate impact but then enjoyed job growth (such as public administration and safety services), and those that suffered heavy losses (such as accommodation and food services).

Another performance gap relates to the subset of industries that were initially hit hardest by the pandemic but which have subsequently enjoyed seen quite different recovery patterns: for example, while both the accommodation and food services industry and the arts and recreation services industry suffered steep job losses at the start of the pandemic, the latter has enjoyed a much more robust recovery than the former, where jobs are still 10 per cent down on pre-pandemic levels.

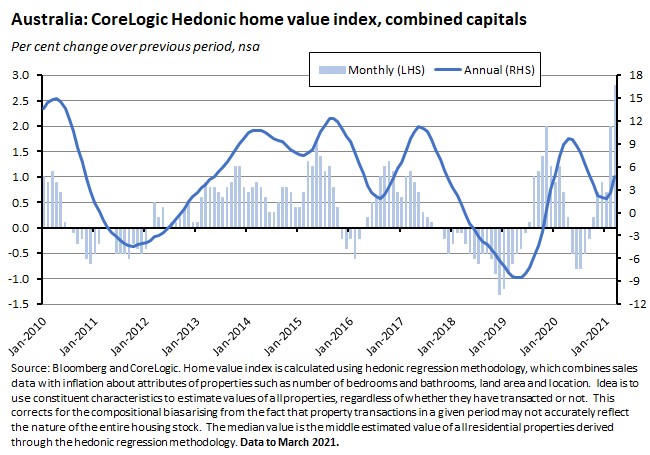

What happened:

CoreLogic’s national home value index rose 2.8 per cent in March 2021 to be up 6.2 per cent over the year. The combined capitals index rose 2.8 per cent month-on-month and 4.8 per cent year-on-year while the corresponding increases for the combined regional index were 2.5 per cent and 11.4 per cent, respectively.

Across the capital cities, the fastest pace of monthly increase was in Sydney (up 3.7 per cent), followed by Hobart (3.3 per cent) and Canberra (2.8 per cent). CoreLogic notes that Sydney dwelling values are now 2.6 per cent higher than their July 2017 peak, meaning that they have now more than unwound both a 14.9 per cent drop in values through to May 2019 and a further 2.9 per cent fall over the COVID downturn. Similarly, Melbourne dwelling values have surpassed their earlier April 2020 peak by 0.2 per cent, according to CoreLogic’s daily hedonic home value index.

Source: CoreLogic

Increases in house values continue to outstrip unit values, with national house prices three per cent higher over the month while unit values were up 1.9 per cent, while across the combined capitals, the quarterly growth rate for houses (6.5 per cent) is more than double that of units (3.1 per cent).

Why it matters:

This was the fastest pace of increase seen in the national index for more than 30 years – since October 1988 – and indicates that Australia’s housing market continues to roar. Inevitably, that is raising questions over the prospects of a ‘housing bubble’ and challenges to financial stability. In the case of Sydney, which led the monthly increases, CoreLogic pointed out that the last time the city had seen a comparable pace of quarterly growth in dwelling values was in June/July 2015, when it was followed by a rapid decline in the pace of growth after the introduction of macroprudential limits on lending to investors kicked in and slowed the market.

CoreLogic nominated the ongoing disconnect between demand and supply as a key factor driving the price action, with total advertised listings remaining low through March (more than 25 per cent below the five-year average). And even though the pace of new listings has now started to pick up, the ratio of sales to new listings is running at around 1.1 (implying for every new listing added to the market, 1.1 homes are sold) which is keeping inventory levels low. More evidence of tight market conditions is visible in auction clearance rates, which remain above 80 per cent.

For now, regulators and the central bank appear relatively relaxed about the state of the housing market (see comments above on the RBA’s latest statement plus readings below for a recent take from APRA’s Wayne Byres) but their current ‘watching brief’ remains vulnerable to the accelerating impact of ‘FOMO’ on the market and any significant deterioration in measures of lending quality such as rising debt to income ratios, rising loan to income ratios or further increases in those already underway in high loan-to-value (LVR) lending and high debt to income (DTI) lending. See also the story below on recent trends in household debt ratios.

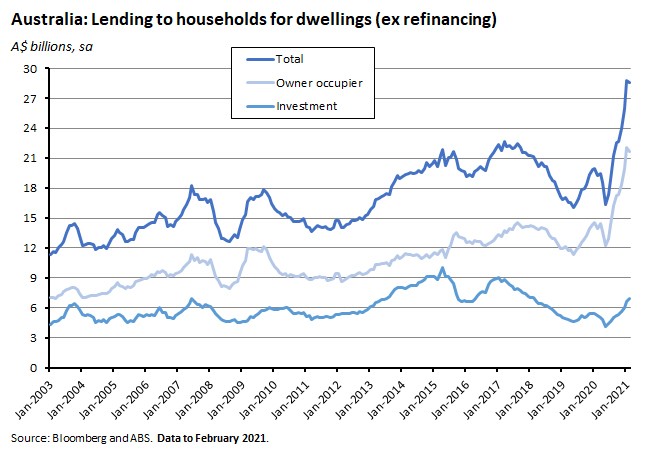

What happened:

The ABS said that in February this year new loan commitments for housing edged down 0.4 per cent over the month but were still almost 49 per cent up over the year. Lending to owner occupiers fell 1.8 per cent month-on-month but rose 55.2 per cent relative to February 2020. Lending to investors was up 4.5 per cent over the month and 31.6 per cent in annual terms.

Personal fixed term loans were up 1.1 per cent over the month and 1.6 per cent over the year. The rise was driven by lending for personal investment which jumped 26.1 per cent.

Why it matters:

Despite a small monthly decline in February (the ABS noted that this was the first fall since May 2020), overall lending into the housing market remains strong, and while it continues to run at close to record levels will also continue to support higher house prices. The loan data also suggest a growing contribution from investors, where lending has been gradually trending higher since hitting a 20-year low in May 2020.

The Bureau also highlighted the ongoing role of the government’s Homebuilder grant, as the value of loan commitments for the construction of new dwellings rose 4.4 per cent, continuing a period of record rises since July 2020. Although the grant, which was introduced in June 2020, was reduced from 1 January 2021, it was also made more widely available to borrowers in NSW and Victoria through increased price caps on new build contracts.

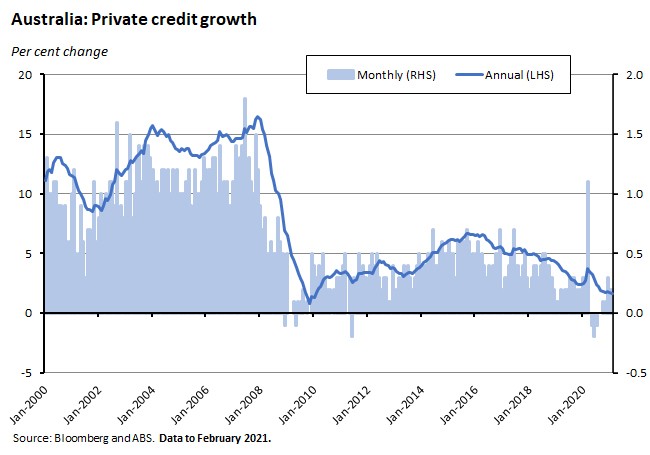

What happened:

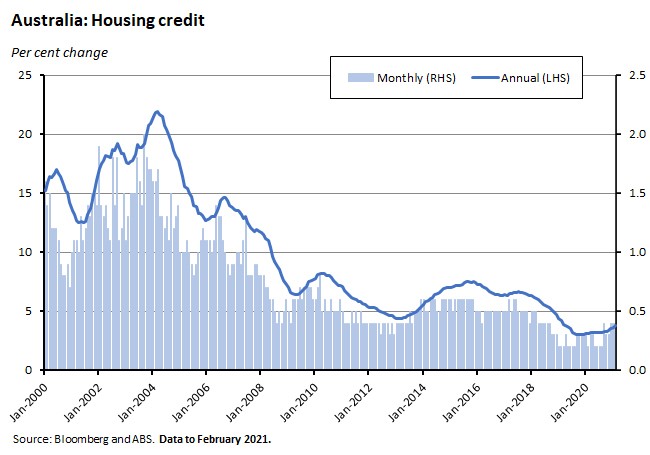

RBA data on financial aggregates showed total credit to the private sector rose just 0.2 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in February to be 1.6 per higher in annual terms.

Housing credit rose 0.4 per cent month-on-month and 3.8 per cent year-on-year, while personal credit fell 0.5 per cent over the month and dropped 12.3 per cent over the year. Business credit was unchanged over the month and down very slightly (by just 0.2 per cent) over the year.

Why it matters:

Total credit growth rose in the early months of the pandemic as businesses drew down lines of credit over March 2020 and April 2020 to bolster their liquidity positions. But as uncertainty receded those credit lines were repaid and since then credit to the business sector has been subdued.

The stock of outstanding credit to the personal sector has tended to decline over the pandemic as households cut back on their use of credit cards and repaid outstanding balances.

Growth in housing credit has picked up since the end of last year in line with the strong activity in the housing market, although rapid growth in new lending for housing has tended to be offset by those households using the pandemic to accelerate their repayments on existing mortgages.

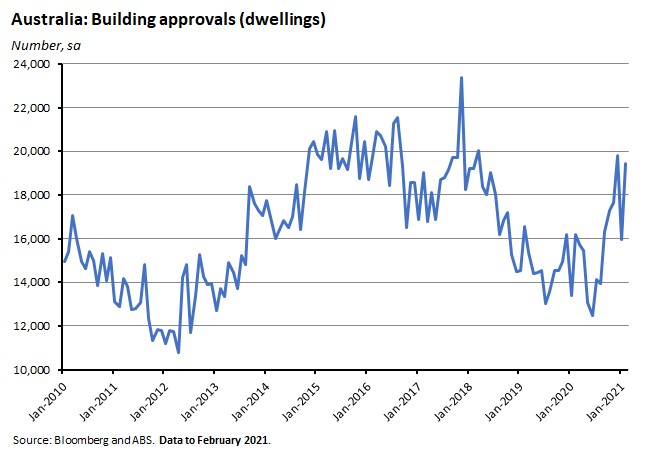

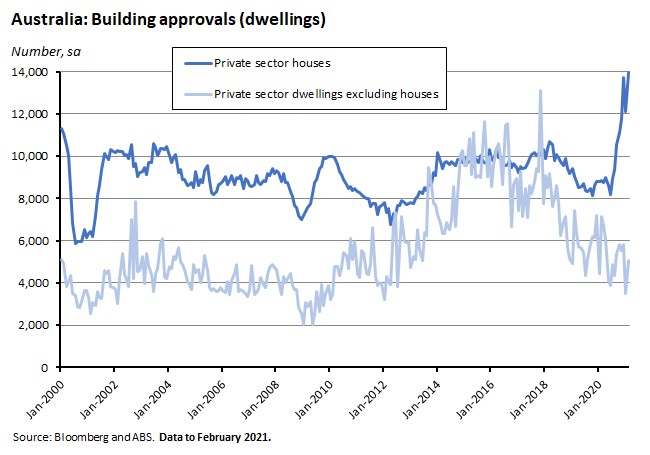

What happened:

The ABS said that the number of total dwellings approved rose 21.6 per cent in February this year (seasonally adjusted) to be 20.1 per cent higher than in the same month in 2020.

Approvals for private sector houses were up 15.1 per cent over the month and 57.5 per cent over the year, while approvals for private sector dwellings excluding housing jumped 45.3 per cent relative to January this year but were still 28.7 per cent lower than the number of approvals in February 2020.

The value of non-residential building approvals also increased in February, rising 27.5 per cent over the month.

Why it matters:

After recording a sharp drop in January, dwelling approvals staged a robust recovery in February. The number of approvals for private sector dwellings reached a new record high of 13,939, beating the December 2020 result. Approvals for apartments and townhouses also enjoyed strong monthly growth after falling to a nine-year low in January, but the numbers were still down in annual terms, reflecting the continuing differential in housing market performance.

The ABS again pointed to the important role of the government’s Homebuilder grant, which was introduced in June 2020 and (after being extended in November 2020) expired at the end of March 2021. Since its introduction, private house approvals have risen by almost 70 per cent. According to Treasury data, over the life of the program to 12 March this year, there had been more than 93,000 applications, of which more than 75,000 were for new builds and the balance for renovation projects.

What happened:

The ABS said that Australian household wealth rose 4.3 per cent ($501.5 billion) to a record $12,033.5 billion in the December quarter of last year, up seven per cent relative to the same quarter in 2019. Average household wealth increased 4.2 per cent ($19,028) over the quarter to $467,709 per person.

Household wealth comprises financial and non-financial assets. Financial assets of households rose 4.7 per cent ($272.6 billion), driven by a $166.2 billion rise in superannuation reserves and a $60.6 billion rise in shares and other equity, while non-financial assets owned by households increased 3.1 per cent ($253.1 billion), reflecting a $250.5 billion rise in land and dwellings.

Household liabilities rose one per cent ($24.2 billion), powered by a $20.1 billion rise in housing loans and a $1.0 billion increase in short-term debt. The rise in housing loans was underpinned by owner-occupier loans, which increased by $21.8 billion. Investor loans contributed $2.6 billion to the rise, recording positive growth for the first time since December 2018. Credit cards were the biggest contributor to the increase in short term debt.

Turning from the household sector to private non-financial businesses, the ABS numbers show the latter reduced their loan balances for a third consecutive quarter, with total loan liabilities falling below pre-COVID levels. Instead of debt, these businesses have turned to equity markets to access capital, issuing a net $70.9b in equities through the year. This produced the lowest debt to equity ratio (0.48 or 0.64 if adjusted for price changes) since the March quarter of 2005.

National capital investment decreased to 22.1 per cent as a proportion of GDP, the lowest proportion seen in the history of the series. Non-financial corporations' investment declined to 9.7 per cent of GDP, general government investment eased slightly to four per cent of GDP, household investment increased to 7.9 per cent of GDP and financial corporations' investment declined slightly to 0.5 per cent of GDP.

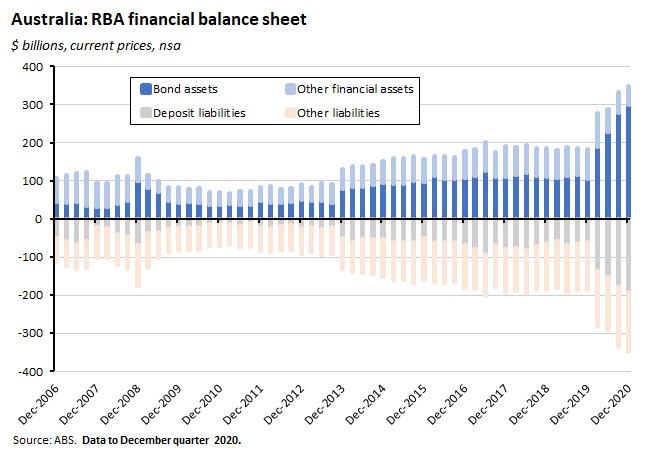

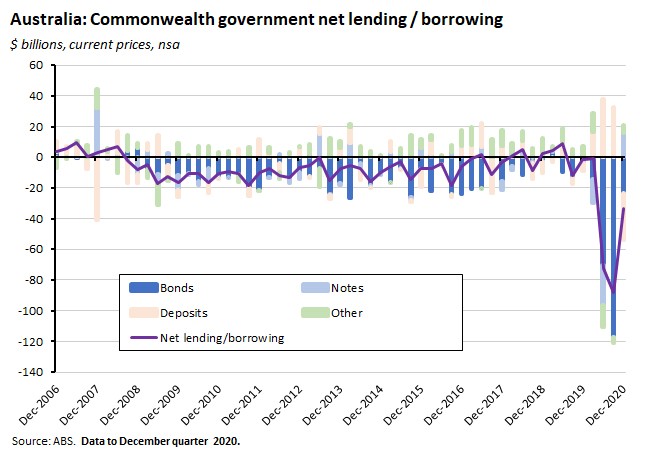

In the case of the government and RBA financial balance sheets during the coronavirus crisis (CVC), Commonwealth Government (measured as national general government) net borrowing in 2020 was $194.8 billion, or nearly four times the $50.4 billion that was borrowed in 2009 during the Global Financial Crisis. Nearly all of this borrowing ($187.1 billion) took place in the June ($72.7 billion) and September ($88 billion) quarters of last year. In the December quarter, the Government reduced its bond issuance, and net borrowing fell to $33.2 billion due to smaller JobKeeper and Boosting cashflow for employers subsidies paid to businesses.

Similarly, state governments also conducted record net borrowing of $89.8 billion in 2020, financed through the issue of semi-government bonds.

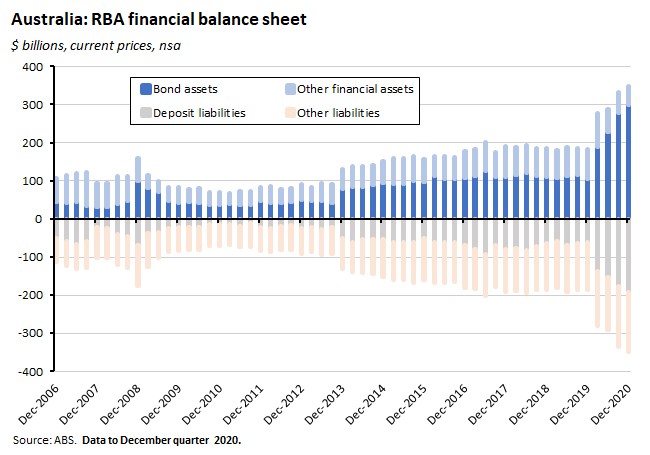

The record issuance of Commonwealth and State government bonds has also played a key role in the RBA’s monetary operations over the past year, which in turn have seen the central bank’s balance sheet expand by 90 per cent since the December quarter of 2019, reflected in rising bond assets and deposit liabilities.

Why it matters:

According to the ABS, the 4.3 per cent increase in total household wealth in the December quarter of last year was the biggest quarterly increase since the December quarter 2009, taking both total household wealth and wealth per capita up to record levels. The largest contributor to the increase was the booming housing sector, with residential assets accounting for 2.2 percentage points of that quarterly growth, rising superannuation balances adding a further 1.4 percentage points and directly held shares 0.5 percentage points.

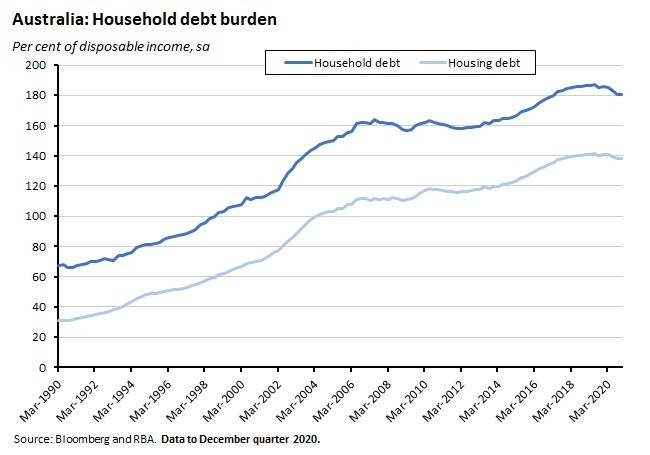

Over the past year there have been modest improvements (that is, declines) in both the debt and debt service burdens of Australian households as income growth – boosted by government support measures including the JobKeeper payments and coronavirus supplement – has outpaced the rise in household debt. For example, although the debt to disposable income ratio (seasonally adjusted basis) edged slightly higher in the final quarter of last year, rising from 180.3 in the third quarter to 180.4 in Q4, that was still down on 185.7 ratio that prevailed in Q4:2019. Similarly, while the ratio of housing debt to disposable income rose marginally from 138.1 in Q3:2020 to 138.2 in Q4:2020, that was still below the ratio of 141 in Q4:2019.

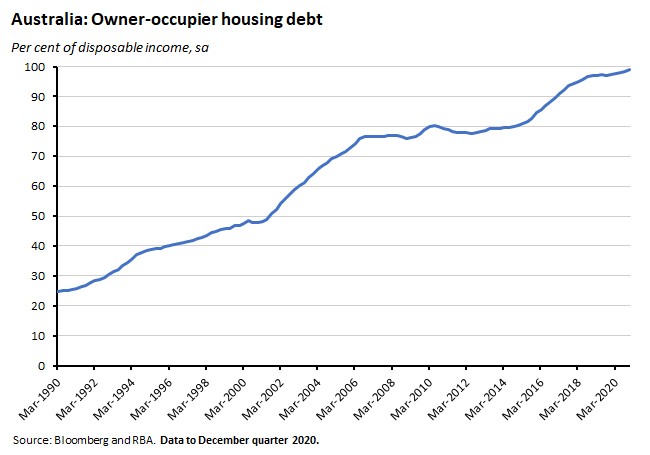

An exception to this story is the case of owner-occupier housing debt, where the ratio to disposable income has continued to rise, hitting a new record high in the December 2020 quarter.

At the same time, lower interest rates have also reduced debt service costs. In the case of debt service, the ratio of interest payments on housing and other personal debt to quarterly household disposable income was unchanged over the December 2020 quarter at 5.9 per cent, but lower than the seven per cent ratio recorded in Q4:2019. Likewise, the ratio of interest payments on housing debt to quarterly household disposable income was again unchanged from Q3:2020 at 4.9 per cent in the December 2020 quarter, down from 5.8 per cent in the same quarter in 2019. The December quarter of 1999 was the last time there was a lower housing debt service ratio than the one that has prevailed over the most recent two quarters of data.

These modest improvements in debt and debt service ratios seem likely to give regulators some comfort – at least for now – when they contemplate the implications of rapidly rising house prices.

What happened:

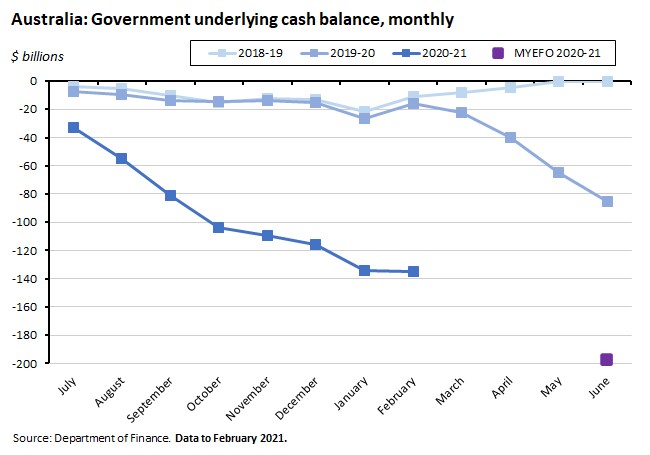

The Department of Finance said that Australia’s underlying cash balance for the year to date in February this year was a deficit of $134.6 billion.

Cumulative receipts were $317.2 billion and cumulative payments were $451.9 billion. The government’s net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) was negative $742.9 million and net debt was $583.3 billion.

Why it matters:

Australia’s faster than expected economic recovery is also delivering better than expected results on the fiscal front, boosting government tax receipts and lowering benefit and other payments.

The MYEFO had expected a year to date deficit of $157.7 billion by February 2021, so the actual outcome of $134.6 billion was a comfortable $23.1 billion below target. That in turn was a product of outperformance on both the receipts and payments sides of the fiscal accounts: actual receipts were $10.7 billion higher than anticipated in the MYEFO projections while payments were $12.3 billion lower than predicted. The improvement in receipts was largely driven by tax receipts running more than $10.5 billion ahead of target, with personal income tax $1.6 billion up on the MYEFO projections, company tax up $2.3 billion, and GST payments up $5.9 billion. In terms of payments, personal benefit payments were $5.1 billion lower than the MYEFO assumptions and grants and subsidies paid were almost $3.5 billion lower.

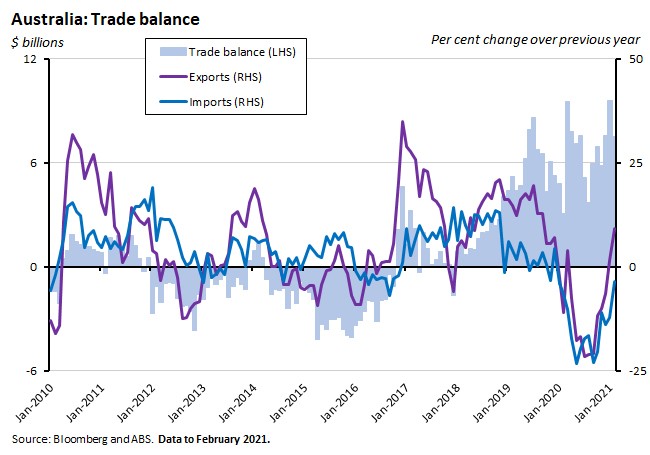

What happened:

Australia’s monthly trade surplus (goods and services) fell by $2.0 billion to $7.5 billion in February (seasonally adjusted). Exports of goods and services were down one per cent over the month but up 9.1 per cent over the year, while imports rose five per cent over the month and were down 3.6 per cent over the year.

Why it matters:

Australia continues to run substantial trade surpluses, supported by strong commodity prices, and that trend will continue into next month. The March 2021 RBA commodity price index rose by 1.6 per cent (on a monthly average basis) in SDR terms, after increasing by a revised 3.1 per cent in February. In Australian dollar terms, the index increased by 1.3 per cent in March. Over the past year, the index has increased by 28.2 per cent in SDR terms, powered by higher iron ore prices. In Australian dollar terms the rate of annual increase is 7.8 per cent.

What happened:

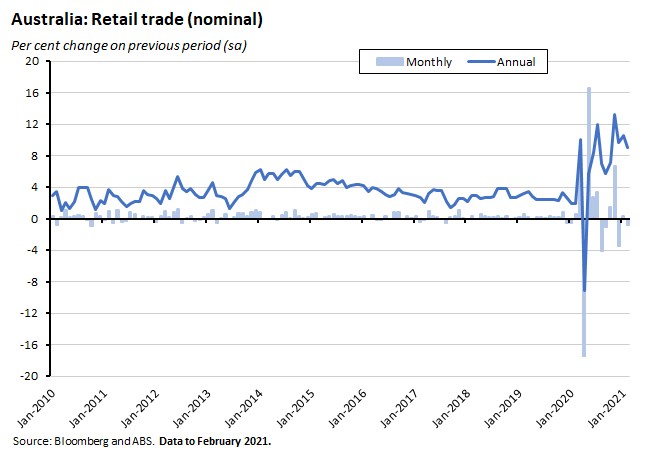

Retail turnover fell 0.8 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) in February this year, but sales were still 9.1 per cent higher than in the same month last year.

By industry, turnover was down three per cent over the month in food retailing and down 0.4 per cent in other retailing. All other industries enjoyed higher sales in February, led by a 2.2 per cent gain for department stores and a 1.6 per cent increase for clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing.

By state, there were monthly declines in turnover in Western Australia (down 5.4 per cent), Victoria (down three per cent) and the Northern Territory (down 2.8 per cent) and gains elsewhere.

Total online sales were 9.3 per cent of total sales in February, up from 9.1 per cent in January 2021 and 6.6 per cent in February last year. In value terms, online sales were 52.5 per cent higher than in February 2020.

Why it matters:

The final estimate of a 0.8 per cent decline in retail turnover came in slightly smaller than the preliminary estimate of a 1.1 per cent drop. Turnover remains well up in annual terms.

What happened:

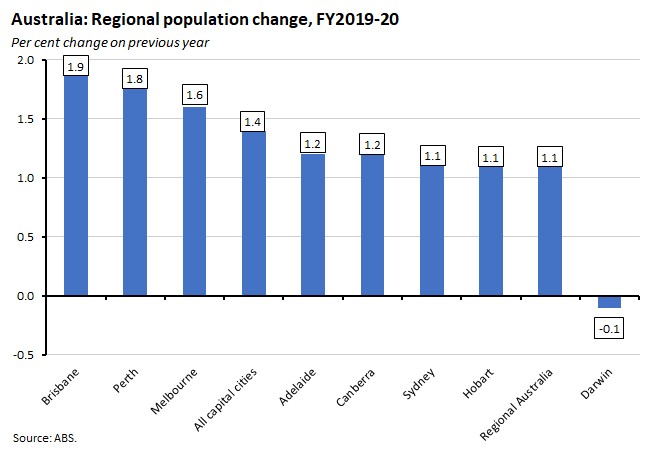

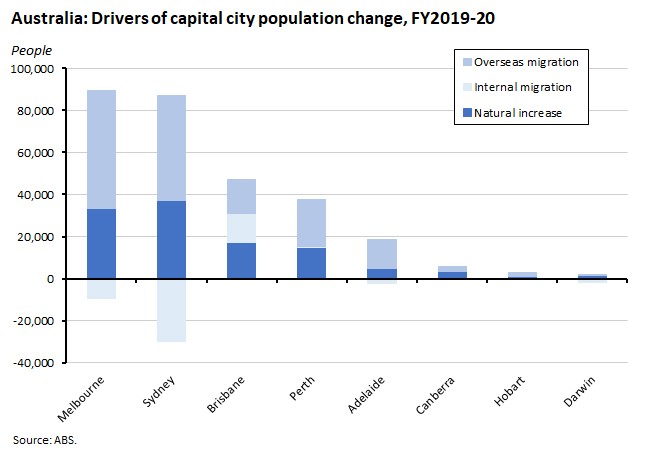

New data from the ABS on regional population growth showed that over the 2019-20 financial year, the number of people living in the capital cities increased by 245,300 (1.4 per cent) while the population of regional Australia rose by 86,200 (1.1 per cent).

Population growth was fastest in Brisbane (1.9 per cent annual growth) and weakest in Darwin (down 0.1 per cent). In absolute terms, the largest gains in population were in Melbourne (up 80,088), Sydney (up 57,107) and Brisbane (up 46,914).

Sydney remained Australia’s largest city in 2019-20, with a population of 5.37 million, ahead of Melbourne with a population of 5.16 million and Brisbane with 2.56 million.

Aggregate capital city growth comprised overseas migration (162,800), natural increase (112,700) and internal migration (-30,200) with the relative contribution from each factor varying by city. For example, while net overseas migration was the major contributor to population change in Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, Adelaide and Hobart, natural increase made the largest contribution in Brisbane and Canberra. Net internal migration population losses were the largest in Sydney, followed by Melbourne, Adelaide and Darwin.

Why it matters:

While the 2019-20 numbers offer an interesting take on the population position across Australia, it’s worth recalling that only the closing months of the FY were influenced by the pandemic, so the regional population data for CY 2020 will give a better picture of how COVID-19 has influenced the national distribution of population. Remember, for example, that the Q3:2020 regional internal migration estimates showed that interstate migration slumped relative to the second quarter of that year, and that Capital cities overall had a net loss of 11,200 people from internal migration, the largest quarterly net decline on record.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

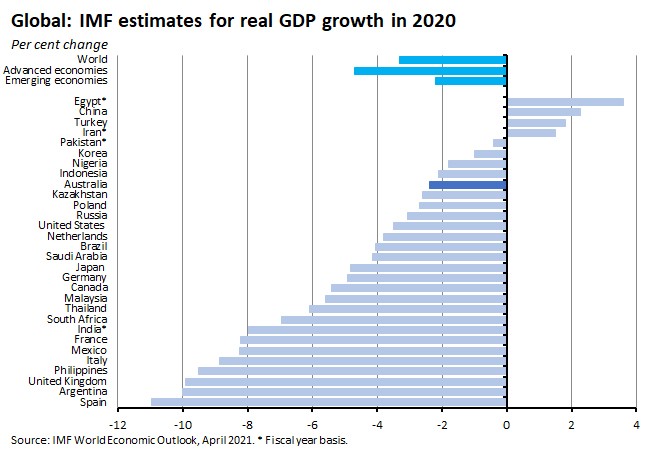

Following a 3.3 per cent contraction in real GDP in 2020, the April 2021 IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) shows that the Fund now expects the world economy to grow by six per cent this year and 4.4 per cent in 2022 (all growth rates on a purchasing power parity basis). That represents forecast upgrades of 0.5 percentage points and 0.2 percentages points, respectively, relative to the January 2021 WEO forecasts.

The good news here is that the IMF expects to see fairly strong growth rebounds across the board, with last year’s large contractions in real GDP (mostly) being followed by sharp expansions in output. In the case of Australia, the Fund is predicting 4.5 per cent GDP growth this year and 2.8 per cent growth in 2022.

So, the IMF sees the pattern of growth going from this…

…to this:

The not-so-good news, however, is that the Fund still thinks that the post-COVID recovery will be uneven and ‘far from complete’, in part because second and third infection waves have triggered renewed restrictions on mobility and generated a ‘stop-go’ rhythm of growth.

The actual and predicted country-by-country variability in recovery is also present in differences across sectors and households and reflects significant variations in the path of the pandemic, the scope and severity of restrictions on activity and mobility, the scope for and scale of the policy response, the generosity of social safety nets, the relative importance of contact-intensive services, the share of ‘teleworkable’ jobs, and access to robust digital infrastructure, along with a range of other factors.

The key assumption that underpins the IMF’s baseline forecasts is that vaccines and other therapies are accessible at affordable prices for all economies, and that this, combined with improved testing and tracing, will see local transmission of COVID-19 running at low levels everywhere by the end of next year. Downside risks to this outlook include the threat of a pandemic resurgence including through the emergence of vaccine-resistant strains and / or through problems with vaccine rollout including delays in production and distribution; tighter financial conditions; extended ‘scarring’ or damage to the supply-side of the economy; increased social unrest; a greater frequency of natural disasters; and geopolitical, trade and technology risks. Potential upside risks include better than expected progress with vaccine production and distribution, larger effects from fiscal support, and potential payoffs from more international policy coordination.

Why it matters:

A six per cent growth result for the world economy this year would be the fastest pace of global economic expansion recorded in the WEO database (which goes back to 1980) – surpassing the previous best of 5.5 per cent growth in 2007.

The IMF emphasises the critical importance of both vaccine rollouts and policy support in driving this global economic recovery. In the case of the former, that involves overcoming production and distribution bottlenecks and ensuring rapid and equitable access as quickly as possible. In the case of the latter, Fund economists estimate that the global policy response already likely contributed six percentage points to world growth in 2020, and that in its absence, the decline in world output could have been three times worse than the actual result.

The United States and Japan have now committed to substantial fiscal packages this year while Brussels is scheduled to start distributing its own (somewhat more modest) Next Generation EU funds. In the case of President Biden’s US$1.9 trillion fiscal plan, the IMF thinks that not only will this give a strong boost to US growth but that it will also generate positive spillovers to trading partners.

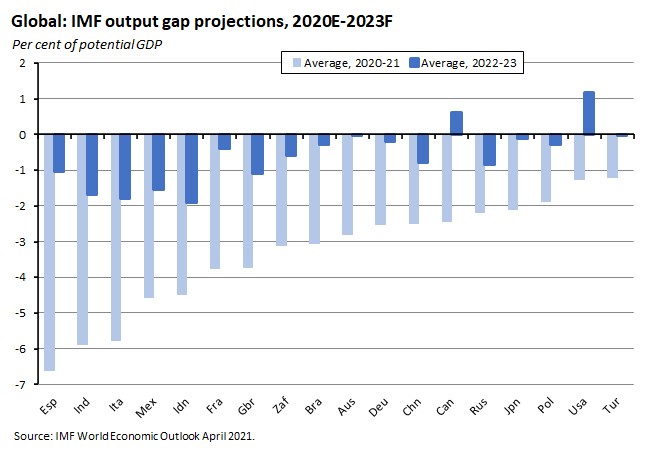

Echoing the RBA, the Fund is also relaxed about inflation risks, arguing that although commodity prices are now headed higher, ongoing labour market slack in particular and large output gaps in general mean that underlying inflation will remain contained.

The Fund does concede that estimating output gaps – always far from an exact science – is particularly tricky in the aftermath of a pandemic, since physical distancing and curbs on contact-intensive activity lead to falls in both demand and supply. Still, its best guess is that for most economies there remains substantial spare capacity. Only a handful (including the United States and Canada) are expected to have closed their output gaps by 2023.

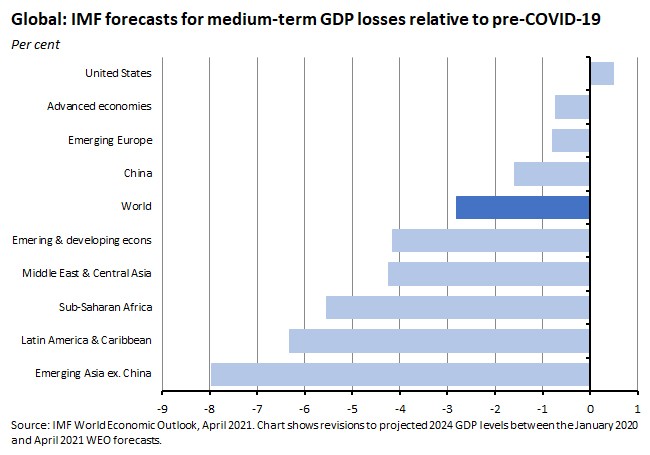

In the medium term, the Fund thinks that global growth will run at around 3.3 per cent, capped by population ageing, persistent damage to potential supply, and China’s shift to a lower growth trajectory. That in turn means that most economies will see GDP levels stuck well below their pre-pandemic trend paths through 2024, again with the United States as a standout exception.

The Fund reckons that the most lasting damage to growth potential from the pandemic will be inflicted on emerging and developing economies (excluding China and emerging Europe), while the corresponding blow to advanced economies is expected to be much more modest.

What happened:

The WTO said that it expects that the volume of world merchandise trade will grow eight per cent this year, bouncing back from a 5.3 per cent contraction in 2020, before slowing to a four per growth rate in 2022. That contraction in 2020 was significantly smaller than the WTO had previously feared – it had predicted a decline of 12.9 per cent back in April this year and then revised that to a 9.2 per cent in October – and reflects a strong recovery that started in the second half of last year.

More evidence of the relatively robust state of global goods trade came from the latest CPB Netherlands World Trade Monitor (pdf), which reported that global trade volumes rose 2.6 per cent month-on-month in January this year while world trade momentum (measured as the average growth rate in the three months up to the latest data point relative to the average of the previous three months) was 3.8 per cent.

Trade volumes have now climbed to be almost six per cent above their January 2020 level.

Unsurprisingly, the story when it comes to trade in services is considerably less upbeat. The WTO estimates that for the whole of 2020, trade in commercial services fell 20 per cent, with travel and Transport services down 63 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively, with both directly impacted by containment measures. The fall in Other commercial services (which includes financial services and computer services) was much more modest, down only two per cent, while Goods-related services fell 13 per cent.

Why it matters:

Following a sharp contraction at the onset of the pandemic, merchandise trade volumes have staged a V-shaped recovery. The drivers of that bounce back include the relatively rapid re-opening of Factory China, fiscal largesse across the developed world that has sustained the incomes –and therefore purchasing power – of consumers, a shift in consumer behaviour in terms of a rising share of online sales along with a reallocation of spending away from services and towards goods, an initial increase in demand for medical equipment include PPE, an increase in demand for technology as firms and households adapted to the WFH revolution, and sustained demand for intermediate and capital goods.

In its own post-mortem on last year’s forecasts, the WTO judged that ‘Strong monetary and fiscal policies by many governments were probably the biggest factors. Much greater in scale and geographic coverage than the response to the 2008-09 global financial crisis, these policies helped prevent a larger drop in global demand, which would have reduced trade further.’ It also pointed to innovation and adaptation by businesses and households that prevented steeper falls in economic activity including the WFH revolution, the resilience of manufacturing supply chains, and trade policy restraint by WTO members, with many of the restrictive trade measures imposed at the start of the pandemic later rolled back alongside the introduction of new liberalising measures.

This changed landscape has not only supported goods trade volumes, however, but it has also generated pressures on global supply chains (seen in the form of shortages ranging from semiconductor chips to shipping containers as well as delays in global ports) and a rising cost of seaborne trade. These pressures have been showing up in global PMI surveys as rising input costs and increased delivery times. And the pressure on already-creaking supply chains was increased still further by the temporary closure of the Suez Canal, which handles around 12 per cent of global shipping, following the grounding of the 1,300-foot, 220,000-tonne Ever Given.

As well as supply chain struggles, the WTO’s latest forecast cautions that the robust performance of global trade is also hostage to a successful global vaccine rollout, warning that ‘as long as large numbers of people and countries are excluded from sufficient vaccine access, it will stifle growth, and risk reversing the health and economic recovery worldwide.’

What I’ve been reading . . .

The ABS provides an overview of key economic statistics to describe Australia’s economic recovery during the final quarter of last year. While the December quarter brought a narrowing in the differences in recovery across states, differences between industries were more persistent.

Grattan on the failings of Australia’s vaccine rollout. Follow up piece here.

The Productivity Commission (PC)’s interim report on Vulnerable Supply Chains. The focus is on imports (the PC notes that the final report will also cover exports). The approach is to apply a series of cuts to the data: (1) identify those imports that are vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, then (2) identify which of these vulnerable products are used in essential industries, and then (3) identify which of this subset of products are critical in the sense that they cannot be substituted easily or the production process cannot be adjusted in the short term to avoid their use. To identify the first category of vulnerable imports, the PC takes 2016-17 import statistics which showed Australia imported 5,950 products worth A$272 billion and then applies three filters to this data: (i) it looks at where more than 80 per cent of imports of a given product came from one source; (ii) where those imports also came from a concentrated global supplier, accounting for more than 50 per cent of global exports of that product; and (iii) did Australia source its imports of that product from that dominant supplier. Using this approach, the PC finds that while 1,327 imported products were highly concentrated, only 518 products would be difficult to find alternative suppliers for, and only 292 products (about five per cent) worth $20 billion met all three criteria. China accounts for a bit more than two-thirds of these vulnerable imports. The PC then looks at the use of these imports as either inputs into essential production or as essential consumption items. It maps 281 of these imports onto production data and finds that only 130 are used by essential industries, indicating that only around two per cent of Australian imports that are from a single, concentrated source are also used in essential industries (which the Commission also suggests is probably an overestimate). In terms of policy, the PC thinks that in general most supply chain risks are best managed by individual firms, but that government could have a role where the whole market for an essential product is at risk (essential products include items such as PPE, chemicals used to treat drinking water and pharmaceuticals). Potential approaches canvassed by the report include supporting a rules-based trading system or requiring firms to take additional precautions such as keeping larger stockpiles or diversifying their suppliers if there is evidence that firms are not adequately managing their risks. But the Commission is sceptical about building domestic capacity as a solution, arguing that this will typically be a ‘very high cost option’, that domestic manufacturing ‘could not achieve efficient scale’, and that it could crowd out risk mitigation by firms.

The March 2021 Resources and Energy Quarterly is now available. The report sees Australia’s resource and energy export earnings rising to a record $296 billion in 2020-21 and then falling by a modest three per cent to around $288 billion in 2021-22.

- The value of iron ore exports is predicted to reach a record $136 billion in 2020-21 and then remain above $100 million (in real terms) each year for the next five years.

- LNG exports are predicted to rise from $33 billion in 2020-21 to $45 billion in 2025-26 (in real terms).

- The story for coal exports is more mixed,: exports of metallurgical coal (used primarily in steel-making) are forecast to rise from a low of $23 billion in 2020-21 to more than $30 billion (in real terms) by 2025-26, while exports of thermal coal, after falling from $20 billion in 2019-20 to just $14 billion in 2020-21 are only forecast to rise to $15 billion (in real terms) by 2025-26.

- Australia’s gold exports are forecast to hit a record $29 billion in 2020-21 before easing to $22 billion by 2025-26 (in real terms).

- The global uptake of new and low emissions energy technologies is expected to see a surge in exports of lithium, nickel and copper with revenue from these three commodities projected to exceed current thermal coal revenue (in real terms) by 2025-26.

Also from the Department of Industry, the latest Australian Innovation System Monitor – March 2021 edition.

The RBA’s April 2021 chart pack is now available.

Also from the RBA, this new Research Discussion Paper applies the growth-at-risk (GaR) framework to the Australian economy. Non-technical summary here (pdf). The GaR framework is designed to answer the question, If there was a financial crisis, how large could the economic losses be? and links current financial conditions to the probability distribution of future economic outcomes with a focus on the left tail of the distribution – that is, on downside risk. To implement the GaR, the authors develop a new financial conditions index (FCI) for Australia that tracks when conditions are generally ‘restrictive’ vs ‘expansionary.’ They find that their FCI provides information about downside risks to future GDP and employment growth and upside risks to changes in the unemployment rate.

ANZ Bluenotes looks at rising Australian house prices.

See also Michael Keating on the risks of a house price bubble.

Also related, for an official take on the housing market, see this recent APRA Chair Wayne Byres speech to the 2021 AFR Banking Summit. Byres covered several macroeconomic issues, including the likely future trajectory of non-performing loans as well as the implications of rising house prices:

- ‘The signs are good that any further increase in impaired assets will be quite manageable – rather than a major surge – given the improvement in underlying economic conditions.’But the longer-term outlook is complicated by structural shifts in response to ‘changes to the way we shop, work, travel and entertain ourselves and, for some, even where we live. All of this, and its impact on credit quality, will take time to play out.’

- With regard to rising house prices, APRA has ‘no mandate to target the level of housing prices, or act to improve housing affordability. For us, housing prices are a risk factor, not a goal.’

- And for now, APRA sounds sanguine about those risks: ‘Household debt levels are undeniably high but have declined relative to income recently. Serviceability of that debt is also being supported by historically low interest rates.’ (See the earlier story on household wealth in the data section).And ‘lending statistics do not show major signs of a return to higher risk lending. The shares of investor lending and interest only lending … are below where they were 18 months ago, and well down on the previous cycle…the shares of high LVR (loan to value) lending, high DTI (debt to income) lending and broker-originated lending are increasing albeit not at a particularly rapid rate, and at least some of this is simply a product of the relatively high share of first home buyers entering the market.’

- But APRA will maintain a watching brief: ‘We are alert to signs that very low interest rates and rising housing prices create a dynamic in which households seek to take on even higher debt levels, and that banks searching for credit growth seek to accommodate that demand through greater risk taking. That could be in the form of looser lending standards, relaxing portfolio limits, or simply not adjusting to market developments…Should risks materialise we have a range of tools we could employ, ranging from interventions similar to that in 2015 and 2017, to the countercyclical capital buffer and (if appropriate) the new non-ADI lending rules.’

Saul Eslake in the AFR is less sanguine than Byres on recent trends in the quality of lending and also thinks that the pace of the recovery may force earlier monetary policy tightening than the RBA expects.

Related, Shane Wright in the SMH asks, has the RBA failed Australians?

This piece from the Conversation examines the ‘giant real-world experiment’ that Australia conducted during the pandemic when it boosted unemployment benefits and removed the ‘mutual obligation’ requirement to apply for jobs. Citing online survey results, the authors argue that recipients found the measures helped, rather than discouraged, recipients look for work. Related, Peter Martin argues that changes to JobSeeker will have adverse consequences for stress and mental health.

Adam Triggs on what Australia should do about China.

Surging house prices are not just an Australian story: here is the WSJ on how house prices are inflating around the world, powered by pandemic-driven government spending, low interest rates and changes in buying patterns. The Economist detects a ‘race for space’ as prices rise faster in less populous but still commutable areas relative to city centres.

As well as the new World Economic Outlook discussed above, the IMF also released the April 2021 editions of its Global Financial Stability Report and Fiscal Monitor.

Eswar Prasad on the global economy’s uneven recovery.

Nice article from Bloomberg Businessweek that attempts to apply Goodhart’s Law to several recent phenomena. (The ‘law’ states that ‘Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes’ and originally formed a critique of the policy implementation of naïve monetarism, noting that in the UK experience, once a particular definition of the money supply was introduced as the basis for monetary policy, the stability of its statistical relationship with spending in the economy would then break down, rendering the policy ineffective. For more on the background, see here. The law was later boiled down by Marilyn Strathern to the more popular proposition that ‘When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.’

Yet more on how the pandemic has transformed the way we (or in this case, US workers) work: ten ways office work will never be the same.

Two columns from VoxEU on the pandemic. The first argues that while lockdowns (‘non-pharmaceutical interventions’) have been key to containing the impact of COVID-19, a cross-country study suggests that the efficacy of lockdowns declines over time. And the second argues that there is in fact no clear trade-off between health and wealth, with those countries that pursued an ‘eliminationist’ strategy enjoying better economic outcomes than those that have ended up with a European-style stop-go approach.

Noted but not yet read: The Peterson Institute has released Economic Policy for a Pandemic Age.

Also noted but not read: The 2021 World Development Report: Data for better lives.

From Brookings, Huawei meets History. This is a look at the historical relationship between great power competition and telecommunications going back to the 1840s but with a particular focus on the lessons from Britain’s ‘information hegemony’ that allowed it to ‘cut Germany off from virtually all global telecommunications in World War I and forced Berlin to route traffic over British-owned lines susceptible to British monitoring, which later proved decisive in Germany’s defeat in the conflict.’

The Atlantic on how mRNA technology could change the world.

An FT Big Read on Archegos and the world of the family office. The WSJ also goes inside the Archegos meltdown. And here is the Economist’s take on events.

Two podcasts to finish. First, John Edwards in conversation with Jennifer Hewett on Australia’s economy after COVID-19. Second, one year on from their first COVID-19 discussion, Russ Roberts and Tyler Cowen revisit the pandemic for Econtalk.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content