Consumer confidence rose again (just) for an eighth consecutive week and there are now accompanying signs of a recovery in consumer spending as captured by bank credit and debit card data. Financial market sentiment towards the Australian economy has also improved, likely driven by good public health results and a gradual re-opening of the economy.

Other data continue to tell a more negative story as private capital expenditure slumped for a fifth consecutive quarter in Q1 and projections for capex next year have been slashed. Construction work done also fell again in the March quarter. Preliminary Australian trade data for April shows iron ore continuing to deliver a strong export performance, despite world trade volumes suffering their largest fall since the GFC the month before. The ABS has delivered another survey update on how business is coping with the coronavirus crisis (CVC). The PM introduced us to ‘JobMaker.’

This week’s readings include that JobKeeper error, economic scenarios for the recovery, clashing economists, chips and geopolitics, the global tourism collapse and Wall Street’s bad (corporate) debt problem.

Finally, one last plug for next week’s webinar on the international economic landscape – details are here.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence index rose by 0.4 points to 92.7.

Why it matters:

While this week’s increase was a very modest one, it still delivered an eighth consecutive weekly rise in consumer confidence. As a result, the index is now up 42 per cent from its low point of 65.3 in March, when fears about the pandemic were at their most extreme. While confidence is still well below its long-term average, consumers are now feeling significantly better than they were a couple of months ago.

What happened:

Several indicators have suggested a degree of stabilisation in the economy now after a couple of terrible months. The payroll data discussed last week was pretty awful in absolute terms, but did suggest a slowing in the rate of job destruction, for example. And as noted above, the ANZ-Roy Morgan weekly measure of consumer confidence has now risen for eight consecutive weeks. Consistent with the latter, there are also signs of a recovery in consumer spending. A weekly index of consumer spending compiled by Alphabeta and Illion suggests that total consumer spending is now running at about 97 per cent of its ‘normal level’.

Likewise, credit and debit card data collected by the major banks also show total spending picking up in May (although they caution that some of this rise might reflect a shift in spending patterns as stores encourage consumers to stop using cash).

The stock market has also been pricing in a more optimistic view of the world in recent weeks. It has risen from a low of 37 per cent below its late February peak to a not-quite-as-bad 19 per cent below. The Australian dollar has also recovered much of the ground it lost earlier in the year.

Why it matters:

The recovery in consumer confidence and the pick-up in market optimism likely both reflect better news on the public health front and the consequent hope for an earlier than expected relaxation of some restrictions on the economy (although do see last week’s note for a discussion of the difficulty in interpreting what financial markets are actually telling us at the moment).

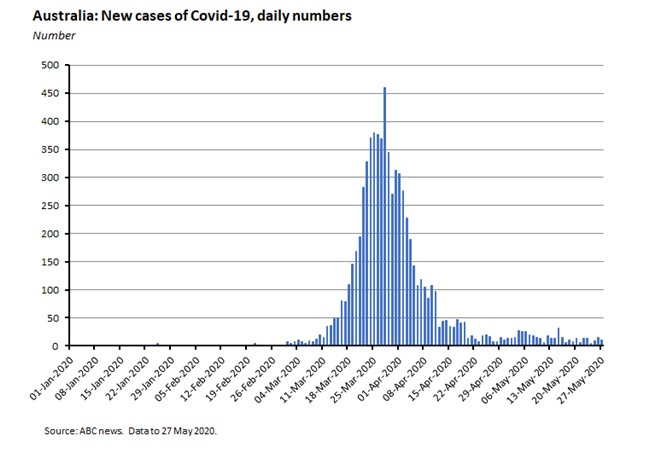

The number of new COVID-19 cases has been low for several weeks now:

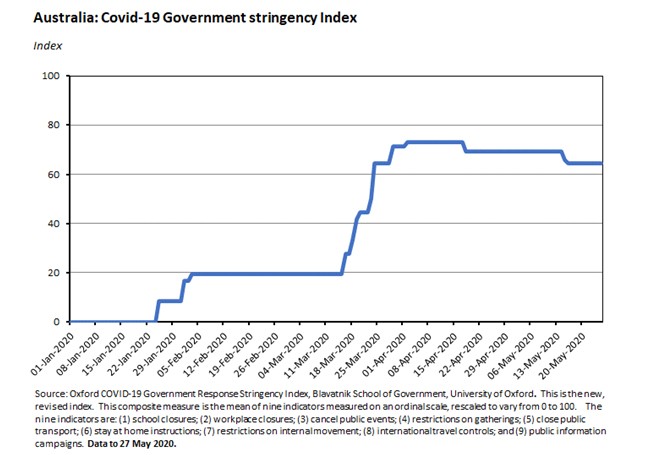

And that in turn has allowed the government to start loosening the economic lockdown:

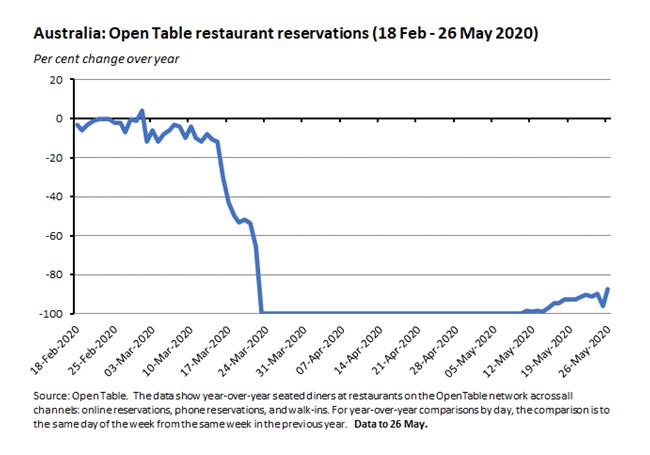

As a result, we’re starting to see some – very – early signs of a return to life in hitherto moribund parts of the economy.

Obviously, it’s very important not to overplay any of this. Many economic indicators are still telling a dreadful story right now, and there will be more bad news to come as results from what will be a terrible second quarter roll in over the coming months. There are also a range of significant risks to the outlook. The most obvious of these is that the current recovery in confidence and the easing of lockdown measures are both very much hostage to continued good news on the public health front. And there are a range of other economic, financial and geo-economic and geo-political risks, too. Still, even keeping all those caveats in mind, it’s good to see some lines on charts heading in the ‘right’ direction for a change.

What happened:

New private capital expenditure fell by 1.6 per cent in the first quarter (seasonally adjusted) to be down a little more than six per cent over the year. According to the ABS, expenditure on buildings and structures fell by 1.1 per cent and spending on equipment, plant and machinery fell by 2.3 per cent.

By sector, mining rose 4.2 per cent in the March quarter and manufacturing was up 5.7 per cent but other industries fell 5.2 per cent.

The ABS also reported the latest estimates for expected new capital expenditure for the current and next financial years:

- Estimate six for 2019-20 was $115.4 billion, which is 3.8 per cent lower than the previous estimate for 2019-20 and 5.6 per cent lower than Estimate six for 2018-19.

- Estimate two for 2020-21 was $90.9 billion, which is 8.8 per cent lower than the first estimate for 2020-21 and 7.9 per cent lower than the corresponding Estimate two for the current financial year.

Why it matters:

The actual 1.6 per cent drop in Q1 capital spending was better than market expectations for a 2.6 per cent fall, thanks to growth in mining and manufacturing expenditure that partially offset the fall in other industries capex. Even so, total private capex has now contracted for a fifth consecutive quarter, continuing the story of weak investment that was a depressing feature of last year’s economy. Moreover, the level of expenditure in the March quarter of this year was the lowest result in more than a decade: we have to go all the way back to the September quarter of 2009 to find a weaker outcome.

Not surprisingly, the negative impact of COVID-19 on investment prospects is apparent in the forward estimates for future capital spending, both of which were down relative to the previous quarterly estimates and compared to the corresponding estimates from the previous year. Capex for the current financial year is now expected to be just $115 billion, while the estimate for next year is even lower, at a little less than $91 billion.

What happened:

The ABS said that the value of construction work done fell one per cent over the March quarter (seasonally adjusted) to be down 6.5 per cent over the year. Building work fell one per cent over the quarter with residential building construction falling by 1.6 per cent and non-residential work unchanged. In annual terms, residential building construction dropped by 12.5 per cent while non-residential work dipped by 0.3 per cent.

Engineering work done in Q1 was down 1.2 per cent relative to the December quarter and down 6.5 per cent over the year.

Why it matters:

The one per cent drop in construction work done was smaller than the market’s expectations of a 1.5 per cent fall in Q1 but that still left work done down about 25 per cent from its Q2:2017 peak. Meanwhile, the value of residential construction has now fallen in every quarter since the second quarter of 2018.

What happened:

The ABS released preliminary data on April’s trade results. The numbers show that exports fell 12 per cent over the month, while the value of imports dropped by five per cent (original terms).

The fall in export values was driven by a decline in exports of non-rural goods, which were down eight per cent, and exports of non-monetary gold, down 47 per cent. That drop in gold exports was the product of a fall in exports to the United Kingdom and Hong Kong following a jump in exports to both countries in March. The decline in imports reflected lower purchases of intermediate and other goods (down six per cent), lower imports of non-monetary gold (down 42 per cent) and lower imports of capital goods (down seven per cent). By product, imports of petroleum, aircraft and road vehicles all fell in April, with the former reflecting lower global oil prices.

The ABS also noted that imports of laptop computers from China remained strong last month, in line with increased demand for home office equipment during the COVID-19 lockdown period, while there were also increases in imports of goods associated with virus detection and prevention such as testing kits and personal protective equipment.

Why it matters:

Despite a $4 billion drop in export values from March’s record outcome, the value of Australian exports in April remained relatively high – about one per cent above the corresponding month last year. That means that the value of Australian exports is holding up relatively well in the face of slowing world trade (see below). A significant reason for that resilience is the continued strength in our exports of resources in general and of iron ore in particular, where prices remain close to US$100/t on the back of fears about disruption to Brazilian production and exports due to COVID-19. To provide a bit of context for that price result, remember that this year’s budget was originally based around the assumption of an iron ore price of just US$55/t.

What happened:

The ABS published the latest in its series of business surveys on the impact of COVID-19, this one covering the period 13 – 22 May. Key findings included:

- 74 per cent of actively trading businesses reported they were operating under modified conditions due to the virus;

- More than 50 per cent of businesses in every industry said they were operating under modified conditions, with the sectors most affected including Information media and telecommunications (96 per cent), Health care and social assistance (93 per cent), Accommodation and food services (92 per cent) and Education and training (91 per cent);

- 72 per cent of all businesses reported decreased revenue as a result of COVID-19;

- By industry, businesses in Transport, postal and warehousing were the most likely to report a fall in revenue (95 per cent) and while more than half of all businesses in Retail trade (53 per cent) reported that that revenues were down as a result of COVID-19, 44 per cent said revenues had increased as a result of the pandemic;

- Over half (55 per cent) of all businesses reported they had accessed wage subsidies such as JobKeeper or apprenticeship wage subsidies, 19 per cent reported having renegotiated property rent or lease arrangements, 16 per cent said they had deferred loan repayments and 38 per cent said they had accessed other government support measures; and

- More than half of all businesses (53 per cent) said that hours worked by staff had reduced, while a quarter (24 per cent) said they had reduced the total number of employees working for the business.

Why it matters:

The survey shows both the widespread impact of the CVC across Australian businesses and the significant and continuing dependence on government support, with almost three quarters of businesses reporting that they have accessed at least one support measure.

What happened:

The Prime Minister gave a speech at the National Press Club focussed on how Australia will recover from the CVC. He declared that ‘the reopening of our economy must be followed by a concerted effort to create momentum and to rebuild confidence…[to]…provide the platform to reset our economy for growth over the next three to five years, as Australia and the world emerges from this crisis. The overwhelming priority of this reset will be to win the battle for jobs.’

As part of that ‘battle for jobs’, the PM stressed the importance of a ‘JobMaker’ plan that would ‘enable Australia to emerge from this crisis and set up Australia for economic success over the next three to five years.’ According to the PM, JobMaker will cover a wide range of policies, encompassing ‘skills, industrial relations, energy and resources, higher education, research and science, open banking, the digital economy, trade, manufacturing, infrastructure and regional development, deregulation and federation reform, [and] a tax system to support jobs and investment,’ but in this week’s speech he focussed on the first two items in that lengthy list: skills and training, and industrial relations (IR).

On skills and training, the PM set out four priorities:

- Better linking funding to current and projected skills needs.

- Simplifying the system, reducing distortions and achieving greater consistency between jurisdictions, and between VET and universities.

- Increasing funding and transparency and performance monitoring.

- Better coordination of current subsidies, loans and other sources of funding.

And on IR there were another five priorities:

- Award simplification.

- Enterprise agreement making.

- Casuals and fixed term employees.

- Compliance and enforcement.

- Greenfields agreements for new enterprises.

The vehicle for progressing these IR reforms will be ‘a new, time-bound, dedicated process bringing employers, industry groups, employee representatives and government to the table to chart a practical reform agenda, a job making agenda, for Australia’s industrial relations system.’ There will be five working groups to cover the five priorities listed above, chaired by the Minister for Industrial Relations and with a working deadline of September.

Why it matters:

As the economy moves towards a gradual relaxation of the lockdown measures, the government’s attention has inevitably turned to what comes next. The list of policies falling under the new ‘JobMaker’ designation is a long one, and it would be no surprise if more are added. The government has also indicated that it will place significant weight on (some of the) past recommendations from the Productivity Commission (PC), including the 2017 Shifting the Dial five-year productivity review, as well as other policy reviews.

Some of the messages on skills and training echo the findings of last year’s Joyce Review of Australia’s Vocational Education and Training (VET) System, which cited ‘slow qualification development, complex and confusing funding models, and ongoing quality issues with some providers’ and advocated for the creation of ‘a new National Skills Commission (NSC) to start working with the States and Territories to develop a new nationally-consistent funding model based on a shared understanding of skills needs.’ The proposed NSC is due to be established later this year while towards the end of last year the government asked to the PC to examine ‘how well the Australian, State and Territory governments have achieved their goals for the VET system as set out in the National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development, and the suitability of this agreement for the future.’ An interim report is due early next month.

On IR, the PC reported on Australia’s workplace relations (WR) back in December 2015. It’s judgment back then was that ‘Contrary to perceptions, Australia's labour market performance and flexibility is relatively good by global standards…Strike activity is low, wages are responsive to the economic cycle and there are multiple forms of employment arrangements that offer employees and employers flexible options for working…Australia's WR system is not dysfunctional - it needs repair not replacement.’ But the PC also went on to acknowledge that ‘Nevertheless, several major deficiencies need addressing’, including suggested reforms to the Fair Work Commission and the benefits of a no-disadvantage test over the better off overall test.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

World trade volumes fell by 1.4 per cent over the month in March to be down 4.3 per cent over the year, according to the CPB’s world trade monitor. Volumes shrank by 2.5 per cent in the first quarter.

Why it matters:

The annual drop in March was the largest fall in world trade volumes since the global financial crisis, and most forward-looking indicators suggest a much steeper decline lies ahead in the second quarter of this year. Survey reports on new export orders have dropped sharply in recent months, while indicators of air and seaborne freight, and of port traffic, have all tumbled. The WTO’s goods trade barometer, which aggregates several of these measures into a single indicator, is currently at its lowest level since the barometer was created and according to WTO economists is consistent with the Organization’s 8 April forecast of a contraction in world trade volumes of between 13 per cent and 32 per cent this year.

Source: WTO

What I’ve been reading:

Here is the Hansard report of Treasury’s testimony to the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 from last Thursday, which included a discussion of the state of the labour market and global economic and financial conditions. Note that this took place before the revised estimates for JobKeeper were announced. (The weekly note was finalised before RBA Governor Lowe’s testimony to the same committee was available online, but we should be able to link to that next week.)

Grattan’s Dannielle Wood on the $60 billion error in Treasury’s JobKeeper calculations.

Deloitte Access Economics present economic scenarios for the recovery.

The AFR recounts how Australian economists have clashed over COVID-19 measures.

Forbes on how COVID-19 and supply disruptions in Brazil are driving another spike in iron ore prices, to Australia’s benefit.

The FT’s Martin Wolf has a wide-ranging column taking in great power rivalry and the future of globalisation. This 2018 paper (pdf) he recommends on the former is well worth a look, too.

A thought-provoking piece from Stratechery on chips and geopolitics, which argues (among other things) that ‘Locked in an endless pursuit of efficiency and shareholder value, the U.S. gave up its flexibility and resiliency in favour of top-end performance.’

Bloomberg looks at the early evidence on the comparative performance of European economies during the CVC. Also from Bloomberg, the global collapse in tourism.

Unherd assesses our addiction to prediction.

Larry Summers is interviewed by the American Interest magazine, with the discussion covering the US-China relationship, a rethinking of supply chains and domestic capacity (more emphasis on ‘just in case’ instead of ‘just in time’), better tax enforcement vs. a wealth tax, a globalisation that is more Detroit and less Davos, and rebuilding the US civil service.

More from Summers: Tyler Cowen thinks that this paper by Summers and co-author Anna Stansbury on the ‘declining worker power hypothesis’ as an explanation of recent US economic trends is one of the best papers of the year.

The New Yorker sets out Wall Street’s bad debt problem, now exacerbated by COVID-19.

In this week’s Dismal Science podcast, we talk about the work of the recently deceased economist Oliver Williamson. For those interested in a more coherent overview of his work than my attempted precis, a nice summary of his thinking on governance can be found here (pdf) and his Nobel Prize (OK, formally the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel) lecture is here.

Timothy Taylor rounds up recent discussion on the future of telecommuting after the pandemic and concludes that face time (no, not that one) will still be important.

Barry Eichengreen wonders whether Schumpeterian creative destruction could be a silver lining to set against the damage the CVC will cause to education, public investment and international trade and global supply chains.

Yanis Varoufakis’s dystopic Chronicle of a Lost Decade Foretold.

Two excellent podcasts to finish with this week. First, Econtalk’s Russ Roberts in conversation with Branko Milanovic on some of the themes in the latter’s new book, Capitalism, alone. (Although only recently released, this podcast was recorded back in February and so is COVID-19 free, which makes for a nice change.) Next, the Talking Politics podcast interviewed History Hit’s Dan Snow about what history can teach us about the current pandemic.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content