The government delivered its much-anticipated Economic and Fiscal Update this week. Ambitions of budget surpluses are now a vanishing dream as Canberra contemplates a deficit expected to approach ten per cent of GDP in 2020-21.

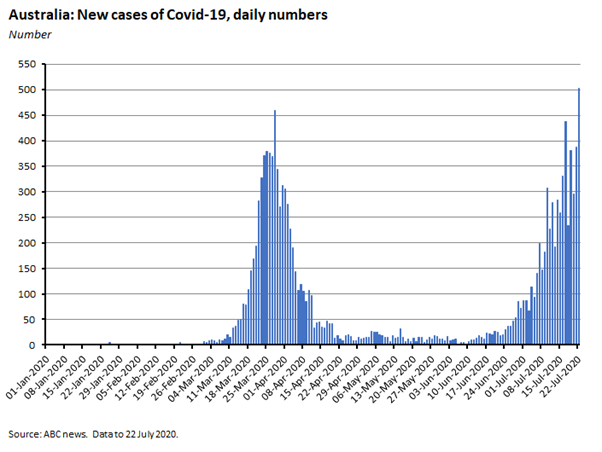

The government also announced extensions to the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs, addressing fears of a looming fiscal cliff in September while trimming the level of support on offer and tightening eligibility criteria. Victoria’s rising COVID cases and return to lockdown are denting consumer confidence, although private sector forecasters have actually become a little more optimistic about the economic outlook this month. RBA Governor Lowe dismissed the case for monetary financing this week and continued to express his scepticism of the merits of either negative interest rates or foreign exchange intervention. But he did hint that 0.25 per cent may not be the effective lower bound for the cash rate after all. Preliminary retail sales data for June provided evidence of renewed stockpiling at the end of last month, particularly in Victoria. And we also squeeze in mention of a big step in the fiscal evolution of the EU.

The Weekly note took a two-week break during the NSW School Holidays. For those who would like an overview of what we missed during that time, and whose appetite for economic commentary hasn’t been killed off by wading through everything that’s come before, I’ve also included an additional section at the end of this week’s note (See: What happened while we were away…) which reviews some of the key data releases over that period including the June labour market report, the latest ABS payroll figures, and the monthly business and consumer confidence numbers. It also looks at developments in global PMIs and China’s Q2 GDP result. That new section replaces the usual readings section this week. But don’t worry - the reading list will return next time, along with what should also be a much shorter note.

If this monster edition of the Weekly hasn’t put you off economics for a while, I’ll be talking in a webinar next week about the July budget update, the RBA’s views on monetary policy and related matters. You can register here.

Finally, my apologies to readers (and my editors!) for the absurd length of this one. It’s been a busy few weeks.

What I’ve been following in Australia . . .

What happened:

The Treasurer delivered the July 2020 Economic and Fiscal Update. The government now thinks that the Australian economy will suffer a real GDP fall of 3.75 per cent this year before GDP growth rises by 2.5 per cent in 2021, while unemployment is forecast to peak at around 9.25 per cent in Q4 this year. Lower revenues and increased spending mean that the underlying cash balance will have moved into a deficit of $85.8 billion (4.3 per cent of GDP) in 2019-20 with that deficit expected to blow out to $184.5 billion (9.7 per cent of GDP) in 2020-2021.

Economic outlook

The global economy is forecast to contract by 4.75 per cent this year while growth in Australia’s major trading partners is expected to decline by three per cent (supported by continued positive real GDP growth in China, the only one of Australia’s top ten trading partners expected to avoid seeing an outright fall in GDP in 2020). Next year, global growth is predicted to pick up to five per cent while major trading partner growth is forecast to rise by 5.5 per cent (including growth of 8.25 per cent in China).

| Real GDP growth, calendar year basis | |||

| % change on previous year | 2019 | 2020F | 2021F |

| Australia | 1..8 | -3.75 | 2.5 |

| Major trading partners | 3.6 | -3.0 | 5.5 |

| World | 2.9 | -4.75 | 5.0 |

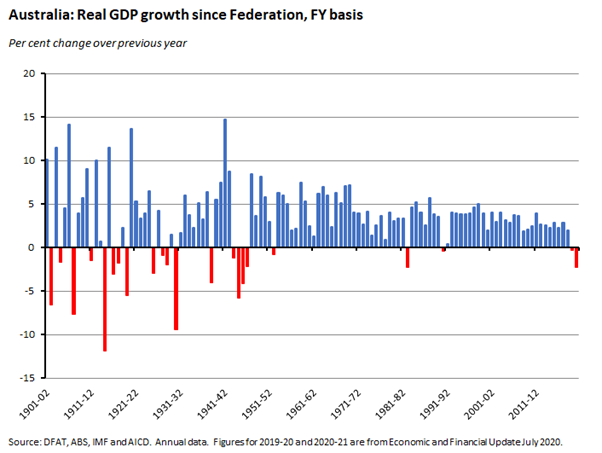

In Australia, GDP is forecast to suffer its largest quarterly fall on record in the June quarter of this year, dropping by seven per cent. Activity is then expected to pick up in Q3, rising by 1.5 per cent, with Treasury estimating that the reintroduction of lockdowns in Victoria will reduce national GDP growth by around 0.75 percentage points in that quarter. For 2020 overall, real GDP is forecast to contract by 3.75 per cent – the largest annual decline in GDP on official record – before growing by 2.5 per cent in 2021.

On a FY basis, growth is expected to have contracted by 0.25 per cent in 2019-20 and is then forecast to fall again by 2.5 per cent in 2020-21 (the worst result since the 1940s). Sitting behind those numbers, lower net overseas migration is expected to contribute to a marked slowdown in population growth, down to 1.2 per cent in 2019-20 and to just 0.6 per cent in 2020-21, which would be the weakest pace of growth since 1916-17.

Household consumption is forecast to have fallen by 2.5 per cent in 2019-20 and to then drop by a further 1.25 per cent in 2020-21, reflecting large declines in household income, wealth and consumer confidence, with consumption of services particularly weak as a result of restrictions on spending on a range of categories.

Dwelling investment is estimated to have contracted by ten per cent in 2019-20 and is expected to slump by 16 per cent in 2020-21.

New business investment is expected to have fallen by six per cent in 2019-20 and is forecast to contract by 12.5 per cent in 2020-21, as public health measures and high levels of uncertainty take their toll on capex plans. There is, however, expected to be a marked difference between mining and non-mining investment, with the former thought to have grown for the first time in seven years in 2019-20 and predicted to expand by another 9.5 per cent in 2020-21 while non-mining investment is forecast to have fallen by nine per cent in 2019-20 and to slump by 19.5 per cent the following year.

New public final demand is forecast to rise by five per cent in 2019-20 and by 4.5 per cent in 2020-21, reflecting continued government spending on the NDIS, transport infrastructure and health care. (Note that most of the government’s COVID-19 stimulus measures will affect household consumption and business investment rather than public final demand.)

| Domestic economy forecasts, FY basis | |||

| % change on previous year | 2018-19 | 2019-20F | 2020-21F |

| Real GDP | 2.0 | -0.25 | -2.5 |

| Household consumption | 2.0 | -2.5 | -1.25 |

| Dwelling investment | 0.0 | -10.0 | -16.0 |

| Business investment | -0.9 | -6.0 | -12.5 |

| Private final demand | 1.0 | -3.5 | -4.0 |

| Public final demand | 4.4 | 5.0 | 4.5 |

| Exports of goods and services | 4.0 | -1.5 | -6.5 |

| Imports of goods and services | 0.3 | -8.0 | -6.0 |

| Nominal GDP | 5.3 | 2.0 | -4.75 |

| CPI | 1.6 | -0.25 | 1.25 |

| Wage price index | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.25 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 5.2 | 7.0 | 8.75 |

| Terms of trade | 5.6 | 1.75 | -12.25 |

| Current account (% of GDP) | -0.7 | 1.75 | -1.25 |

Exports of goods and services are expected to shrink by 6.5 per cent in 2020-21 as exports of services plummet by 32.5 per cent, with exports of tourism and education expected to remain depressed over the whole forecast period. Mining exports are forecast to rise by 0.5 per cent in 2019-20 and by three per cent in 2020-21 as China continues to demand Australian iron ore. Even so, the update makes the conservative assumption that iron ore prices will fall to US$55/t by the end of this year (currently prices are above US$110/t).

Against this backdrop, the official unemployment rate is forecast to continue to rise over the rest of 2020, peaking at around 9.25 per cent in the December quarter and then declining only gradually from the start of 2021 to be around 8.75 per cent by the June quarter of next year. Moreover, Treasury notes that ‘spare capacity in the labour market is expected to be more significant than suggested by the unemployment rate.’ That in turn will put downward pressure on wages and prices, with the wage price index (WPI) forecast to grow at just 1.25 per cent in 2020-21 and the rate of increase of the consumer price index (CPI) to remain subdued, falling by 0.25 per cent over the year to June 2020 and only rising by 1.25 per cent over the year to June 2021.

It’s no surprise that the Update notes that there ‘are significant uncertainties’ surrounding this outlook including the evolution of the virus. Key assumptions underpinning Treasury’s numbers include:

- Restrictions outside Victoria are expected to be lifted in line with the government’s three-step approach with localised outbreaks assumed to be contained to the extent that they do not delay the planned lifting of restrictions.

- In the case of metropolitan Melbourne and the Mitchell Shire, restrictions are assumed to remain in place for six weeks, followed by a gradual reopening from mid-September to mid-December.

- International travel is forecast to remain at low levels until the end of the June quarter 2021.

The Update emphasises that the evolution of the virus ‘is the greatest uncertainty for the domestic outlook’ with either additional significant outbreaks or a substantial worsening of current outbreaks likely to lead to further falls in output and employment. Treasury estimates that GDP was around $4 billion lower relative to the pre-pandemic economy for every week the containment restrictions that applied from late March to mid-May were in place, and calculates that the government’s three-step easing process could quickly claw back about half of that drop. But if similar restrictions were to be reimposed, they would likely cost the economy another $2 billion a week in lost activity, for example. Moreover, there are other uncertainties too, around the pace and shape of the recovery (Treasury thinks the recovery could be relatively fast by historical standards) and around the degree of structural change likely to be triggered by the health and economic shocks, which could further boost the headwinds arising from already-high levels of uncertainty.

Fiscal outlook

The dramatic scale of the economic shock hitting the Australian economy has had equally dramatic implications for the budget. Back at the time of the 2019-20 MYEFO, the government was projecting an underlying cash balance in surplus to the tune of $5 billion (about 0.3 per cent of GDP) in 2019-20, and was expecting a similar outcome (a $6.1 billion surplus, again equivalent to about 0.3 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21. Instead, COVID-19 has pushed the fiscal accounts deep into the red. The 2019-20 underlying cash balance is now expected to record a $85.8 billion deficit (4.3 per cent of GDP) while the in 2020-21 the deficit is expected to blow out to $184.5 billion (9.7 per cent of GDP).

The deficit for 2019-20 has worsened by about $90.8 billion relative to the MYEFO while the budgetary deterioration in 2020-21 is expected to be even larger, at $190.6 billion. That reflects a combination of much lower receipts and significantly expanded payments. For example, total receipts (including Future Fund earnings) are expected to be $33 billion lower in 2019-20 and $61.1 billion lower in 2020-21 than was anticipated in the MYEFO, with tax receipts revised down by $31.7 billion and $63.9 billion, respectively. At the same time, government payments are now expected to be $58 billion higher in 2019-20 and $129.5 billion higher in 2020-21.

| Fiscal outlook | ||

| $ billions | 2019-20E | 2020-21E |

| Receipts | 469.5 | 455.6 |

| Per cent of GDP | 23.6 | 24.0 |

| Payments | 550.0 | 640.0 |

| Per cent of GDP | 27.7 | 33.8 |

| Net Future Fund earnings* | 5.3 | na |

| Underlying cash balance | -85.8 | -184.5 |

| Per cent of GDP | -4.3 | -9.7 |

| Gross debt | 684.3 | 851.9 |

| Per cent of GDP | 34.4 | 45.0 |

| Net debt | 488.2 | 677.1 |

| Per cent of GDP | 24.6 | 35.7 |

Source: Economic and Fiscal Update July 2020. *Net future fund earnings become available to meet the government’s superannuation liability from 2020-21 and are then included the underlying cash balance. Net future fund earnings are projected to be $5.4 billion in 2020-21.

Those swings in receipts and payments reflect a combination of the operation of the so-called ‘automatic stabilisers’ (that is, falls in tax and other receipts as a result of lower economic activity and a parallel rise in payments such as unemployment benefits) and the government’s active policy response to COVID-19 (such as the JobKeeper program). Treasury estimates that most of the fall in receipts relative to the MYEFO’s projections has been due to the operation of the automatic stabilisers and other parameter variations: of the $33 billion decline in receipts in 2019-20, only $0.4 billion of this reflected policy decisions, for example, while of the $61.1 billion projected fall in 2020-21, policy decisions accounted for just $4.7 billion. In contrast, policy actions have driven the bulk of changes to payments: of the $58 billion increase in government spending in 2019-20, policy decisions accounted for virtually all of the total, while policy decisions are expected to account for $113.7 billion of the $129.5 billion of increased payments forecast in 2020-21.

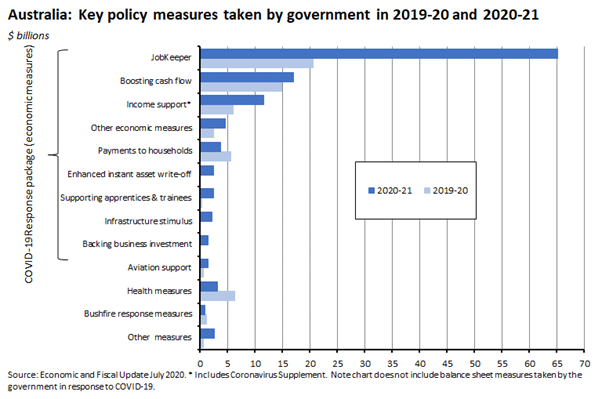

The Update is also at pains to emphasise that the bulk of this policy support has been concentrated in 2019-20 and 2020-21. Of an estimated planned total expenditure of $164.1 billion on economic measures as part of the COVID-19 response package covering the period out to 2023-24, about 31 per cent ($50.4 billion) was spent in 2019-20 and a further 68 per cent ($111.8 billion) is scheduled to be spent during 2020-21. Hence the mantra of ‘timely, temporary and targeted.’

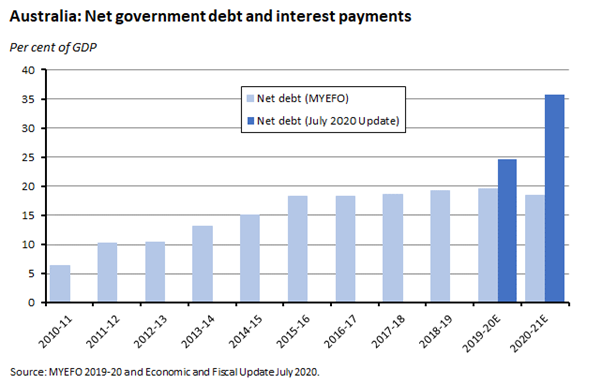

Temporary or not, the combined impact of these developments has been to drive up government debt projections. Gross debt (measured as the face value of Australian Government Securities or AGS on issue) was $684.3 billion (34.4 per cent of GDP) at 30 June this year and is now expected to rise to $851.9 billion (45 per cent of GDP) by 30 June 2021. Net debt is expected to be $488.2 billion (24.6 per cent of GDP) on 30 June this year and is now forecast to increase to $677.1 billion (35.7 per cent of GDP) on 30 June 2021. That’s not that far off double the old MYEFO projections for a net debt to GDP ratio of just 18.5 per cent by end 2020-21.

Why it matters:

The severity of the COVID-19 downturn and the scale of the government’s fiscal response has plunged Australia’s fiscal accounts into an ocean of red ink, setting a new post-WW2 record. Moreover, there’s a decent chance that the actual deficit in 2020-21 will turn out to be even larger: the Update is sensibly explicit about the high level of uncertainty attaching to its economic and fiscal forecasts and the way in which the economy’s trajectory remains hostage to the vagaries of the coronavirus and the risks of further outbreaks like the one currently testing Victoria. Further, the government has already flagged that the July update will not necessarily the be the final word on policy stimulus: depending on the health of the economy come the budget on 6 October, Canberra is likely to be considering other measures. There has been talk about bringing forward the already-legislated tax cuts, for example, and about extending JobSeeker 2.0 beyond the end of this year (see next story).

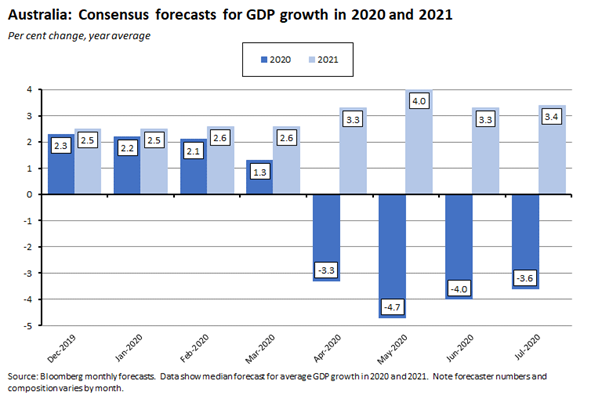

That said, the assumptions behind the Update’s projections are an interesting mix of the optimistic and the cautious. The optimism is found in the assumptions about the speed with which the re-opening of the economy will continue and the situation in Victoria will be brought under control. The caution is apparent in the growth projections, which anticipate a slightly deeper downturn than the latest private sector consensus forecasts for this year (-3.75 per cent instead of -3.6 per cent) and a more subdued recovery in 2021 (2.5 per cent vs 3.4 per cent). The forecasts around the iron ore price are also quite conservative.

The forecast budget blowout will in turn see government net debt as a share of GDP climb to 35.7 per cent at end 2020-21. Still, relative to most of our international peers, at that level Australia’s government debt burden remains modest. Moreover, record low borrowing costs – the lowest since Federation – mean that the interest cost of servicing the increased debt burden will remain fairly flat as a share of GDP. As the governor of the RBA stressed in his speech earlier this week (see below), Australia has ample scope for its aggressive fiscal policy response to date, and the scale of that response has been warranted by the size of the economic challenge. Treasury estimates that the government’s support has increased the level of real GDP by around 0.75 per cent in 2019-20 and will increase it by around 4.25 per cent in 2020-21, relative to the case of no policy support. Likewise, fiscal measures are estimated to have lowered the peak of the measured unemployment rate by around five percentage points (about 700,000 jobs). Or to put it a bit differently, while we might now be swimming in an ocean of red ink, we are swimming, not drowning.

What happened:

The Prime Minister and the Treasurer announced JobKeeper 2.0 and JobSeeker 2.0. The Treasury also published its three-month review (pdf) of the original JobKeeper program.

JobKeeper 2.0

The original JobKeeper payment program started on 30 March and it’s important to remember that it will remain in place until 27 September this year. This program provides a government payment of $1,500 per fortnight per eligible employee for eligible businesses. Business eligibility is based on a turnover test:

- Businesses with an aggregated turnover of $1 billion or less are eligible if their turnover has fallen by or is projected to fall by 30 per cent or more in the relevant month or quarter (depending on their Business Activity Statement reporting period) relative to their turnover in a corresponding period a year earlier;

- Businesses with an aggregated turnover of more than $1 billion are eligible if their turnover has fallen by or is projected to fall by 50 per cent or more; and

- Australian Charities and Not for profits (NFPs) Commission-registered charities are eligible if their turnover has fallen by or is projected to fall by 15 per cent or more.

The extension to JobKeeper – JobKeeper 2.0 – extends the life of the wage subsidy program to 28 March 2021 but also makes several significant changes.

- The previous payment rate of $1,500 per fortnight for eligible employees and business participants will now be reduced to $1,200 per fortnight from 28 September 2020 and then cut again to $1,000 per fortnight from 4 January 2021.

- From 28 September 2020, lower payment rates will also apply for employees and business participants that worked fewer than 20 hours per week.These new rates will be $750 per fortnight from 28 September 2020 and $650 per fortnight from 4 January.

- While the turnover tests for eligibility will still use the same turnover ceilings and percentage falls in turnover as applied to JobKeeper 1.0, there are some additional changes that tighten the criteria quite significantly in a couple of ways:

- From September, businesses and NFPs seeking to claim the JobKeeper Payment will be required to demonstrate that they have suffered the relevant decline in turnover using actual (rather than projected) turnover.

- Eligibility for the first JobKeeper Payment extension period(28 September 2020 to 3 January 2021) will require businesses and NFPs to demonstrate that their actual turnover has fallen by the required amount in the both the June and September quarters relative to comparable periods (generally the corresponding quarters in 2019).

- And eligibility for the second JobKeeper Payment extension period (4 January 2021 to 28 March 2021) will require businesses and NFPs to again demonstrate that their actual turnover has fallen by the required amount in each of the June, September and December quarters relative to comparable periods (generally the corresponding quarters in 2019).

The government reckons that JobKeeper 1.0 is currently supporting around 960,000 businesses and 3.5 million workers, or about 30 per cent of the pre-COVID private sector workforce. As a result of the changes made to JobKeeper 2.0 plus expectations of some improvement in overall economic conditions, Treasury estimates that the number of JobKeeper recipients will decline substantially in the months ahead, dropping to around 1.4 million people in the December quarter of this year before falling again to one million in the March quarter of 2021. There will also be a parallel fall in the number of businesses able to claim JobKeeper support.

The estimated budgetary cost of JobKeeper 2.0 is about $16 billion or around 0.8 per cent of GDP.

The Treasury Review of JobKeeper 1.0

According to the government, the original JobKeeper wage subsidy program was designed to do three things: (1) support business and job survival; (2) preserve the relationship between employer and employee; and (3) provide income support. Treasury’s three-month review concludes that the program met all three objectives.

- The program had a large take-up (as noted above, applying to around 960,000 businesses and 3.5 million workers) over the April-May period.

- As of 23 June, payments had totalled $20.3 billion over the four payment fortnights to 24 May, equivalent to about seven per cent of Q1 GDP.

- The payment went to businesses that experienced an average decline in turnover in April of 37 per cent over the previous year.

- Treasury estimates that around 75 per cent of payments so far have gone to subsidising wages and the balance to income transfers.

The case for continuing JobKeeper beyond its initial termination date of 27 September is supported by Treasury’s view that the official unemployment rate will be around 8 per cent in the September quarter (up from 7.4 per cent now) and that it will rise further in Q4 (see previous story). Treasury also reckons that some sectors, such as tourism and arts and recreation, will remain distressed throughout the remainder of this year and beyond, as a result of the health restrictions that will remain in place, including border controls.

The conclusion of the review argues that the ‘current extent of labour market weakness and the high degree of uncertainty surrounding the outlook for the second half of the year suggest it would be prudent to extend JobKeeper beyond September to businesses that are still distressed.’ It also notes that the introduction of ‘a fresh eligibility test would, in effect, function as an in-built automatic macroeconomic stabiliser. The use of a freshly applied eligibility test based on actual turnover would automatically dial down and target support to those sectors that are still in an environment where they need to preserve jobs.’

JobSeeker 2.0

The original Coronavirus Supplement was first paid on 27 April this year and was expected to run until 24 September 2020. It was paid at a rate of $550 per fortnight to both existing and new recipients of Jobseeker Payment, Youth Allowance, Parenting Payment, Austudy, ABSTUDY Living Allowance, Farm Household Allowance and Special Benefit. The government also temporarily expanded access for the JobSeeker Payment by relaxing the partner income test and by suspending Jobseekers’ mutual obligation requirements from 24 March 2020 until 8 June 2020 (meaning that recipients were not required to attend appointments, look for work or participate in related activities). As of June this year, there were more than 1.6 million Australians receiving JobSeeker payments (including more than 170,00 receiving Youth Allowance – Other).

JobSeeker 2.0 extends the payment period for the Coronavirus Supplement from 25 September 2020 to 31 December 2020. The new supplement will be paid at a reduced rate of $250 per fortnight and the eligibility will be the same as before.

In addition, for the period from 25 September until 31 December, the income free area for the JobSeeker Payment and Youth Allowance will be increased from $106 per fortnight for JobSeeker and $143 per fortnight for Youth Allowance to $300 per fortnight for both, meaning that recipients can earn income of up to $300 per fortnight and still receive the maximum benefit payment.

There will also be changes to the way individuals access JobSeeker payments with effect from 25 September, including the reinstatement of means testing (asset testing and the liquid assets waiting period) and an increase in the taper rate for partner income testing (rising from 25 cents for every dollar of partner income earned over $996 per fortnight to 27 cents for every dollar of partner income earned over $1,165 per fortnight), along with a continuation of the reintroduction of job seeking requirements that began on 9 June.

The estimated cost of JobSeeker 2.0 is about $3.8 billion or around 0.2 per cent of GDP.

Why it matters:

The original JobKeeper package plus the Coronavirus Supplement to JobSeeker were both critical parts of the government’s initial fiscal response to the coronavirus crisis (CVC). At an estimated total budgetary cost of $70 billion (about 3.5 per cent of GDP), JobKeeper alone accounted for more than half of the original $133.8 billion of pledged Commonwealth fiscal support, while the Coronavirus supplement accounted for a further $14.1 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) or more than ten per cent of Commonwealth support. Together, they also apply to more than five million Australians.

Based on Treasury’s estimates (pdf), the combined stimulus from just those two packages in the June quarter of this year was around $25 billion (about 1.25 per cent of GDP) and in the current September quarter the figure will be closer to $59 billion (almost three per cent of GDP). So, with both measures due to expire at the end of September, there had been a growing focus on the potential direct hit to the economy implied by this economic ‘cliff’ and the indirect drag on expectations from the associated uncertainty around future levels of government support.

This week’s announcement seeks to address both these issues while at the same time also tapering the level of support to reduce the cost of both programs (during the Q&A following the release of the changes, the Prime Minister said that Australians ‘know that a current scheme that is burning cash, their cash, taxpayers' cash to the tune of some $11 billion a month cannot go on forever’). By committing to JobKeeper 2.0 until the March quarter of next year and JobSeeker 2.0 to the end of this year – and by doing so well before the end of the existing programs – the government has made a significant contribution towards lowering uncertainty while also injecting additional fiscal support into the economy. That’s two very important positives to come from this week’s announcements.

However, as some commentators have already noted, the economic cliff has now been replaced by an economic slope: if Treasury’s estimates are correct, then the new programs will ‘only’ inject a total of $20 billion into the economy. That’s not exactly trivial, but it is well down on the more than $84 billion provided by the original programs. Of course, part of that wind back reflects the assumption that the economy will be on a firmer footing as recovery kicks in. But if that isn’t the case, the government is likely to find itself looking for additional stimulus measures.

There was also a difference in the time horizons applied to the two schemes, with the government committing to JobKeeper 2.0 until the end of the first quarter of next year while only extending the Coronavirus Supplement through to the end of this year. This gap is somewhat puzzling, although it’s worth noting here that the PM did say in his comments that ‘I am leaning heavily in to the notion that we would anticipate based on what we know right now that there would obviously need to be some continuation of the COVID supplement post-December.’

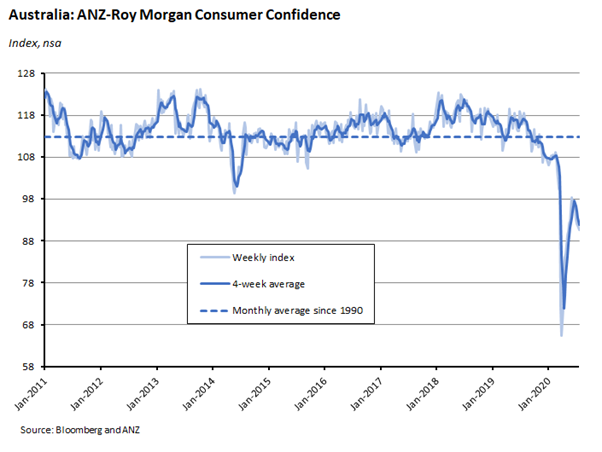

What happened:

The weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan index of consumer confidence fell one per cent to an index value of 90.7 with all sub-indices also falling with the exception of ‘current financial conditions’, which rose by 2.3 per cent. But ‘future financial conditions’ declined 2.5 per cent, ‘current economic conditions’ fell 1.5 per cent and ‘future economic conditions’ fell 2.7 per cent.

Why it matters:

The high number of COVID cases in Melbourne and the increase in Sydney numbers continue to take a toll on consumer confidence.

This was the fourth consecutive weekly fall in the headline index and the fifth in the ‘current economic conditions’ sub-index. The headline index is now at its lowest level for more than two months (although still comfortably above the low reached at the end of March).

What happened:

RBA Governor Philip Lowe gave a speech on COVID-19, the Labour Market and Public Sector Balance Sheets which looked at the impact of the pandemic on Australia’s labour market and the role played by the expansion of the government and central bank’s balance sheets.

On the labour market, the governor argued that we have ‘turned the corner’, with last month bringing a four per cent rise in hours worked and a 210,000 increase in the number of employed people (see also the stories on June’s labour market release and the latest ABS payroll data below). He also noted that many firms that had been heavily affected by the shutdowns were now rehiring and lifting hours, particularly in the retail, hospitality and arts and recreation sectors. Offsetting this good news, however, were some ‘major cross-currents’, as firms in the construction and professional services sectors faced a declining pipeline of work while businesses across the economy were reconsidering their business models, with ‘restructuring and the uncertainty about future demand…likely to weigh on the labour market as it recovers.’ The return of Australians to the labour force also meant that the unemployment rate was still set to rise further. As a result, the governor thinks that ‘the path ahead is expected to be bumpy.’

Turning to the role of public sector balance sheets, Lowe began with the RBA itself, noting that the implementation of the central bank’s mid-March monetary policy package had seen its balance sheet increase from around $180 billon prior to the pandemic to around $280 billion now, with further increases expected over the coming months. He then went on to consider the case for direct central bank funding of the government and the use of ‘helicopter money’ (depositing money directly into every bank account in the country). Lowe’s view here was that there was no free lunch available in terms of funding government spending, arguing that ‘it is not possible to put aside the government's budget constraint permanently. Where countries have, in the past, sought to put aside this constraint the result has been high inflation.’

The governor did concede that ‘some prominent mainstream economists’ have argued recently that central bank financing of government spending may be appropriate in some limited circumstances: when conventional monetary policy had been exhausted, when the central bank is failing to meet its goals, and when public debt is high and governments are unable to borrow in financial markets on reasonable terms. But Lowe went to stress that ‘this proposal is only relevant to the situation where high government debt constrains the ability of the government to provide necessary fiscal stimulus financed through the normal channels. Clearly, it is not relevant to the situation we face in Australia.’

After ruling out monetary financing, Lowe considered other alternative options for monetary policy, including negative interest rates and foreign exchange intervention. In the case of the former, the governor stuck to the line he has taken consistently on this topic, stating that ‘There has been no change to the Board's view that negative interest rates in Australia are extraordinarily unlikely…this is not a direction we need to head in.’ And in the case of intervention in the foreign exchange market, he argued that the ‘evidence here is that when the exchange rate is broadly in line with its economic fundamentals, as the Australian dollar is currently, this approach has limited effectiveness. It can also involve substantial financial risks to the public balance sheet and complicate international relationships. So, this too is not a direction we need to head in.’

As well as ruling out a range of options, however, the speech did allow for the possibility of a change to the parameters of the March monetary policy package. Referring to the discussion covered in the minutes of the July policy meeting, the governor noted that ‘it would have been possible to configure the existing elements of the RBA package differently. For example, the various interest rates currently at 25 basis points could have been set lower, at say 10 basis points. It would also have been possible to introduce a program of government bond purchases beyond that required to achieve the 3-year yield target. Different parameters could have also been chosen for the Term Funding Facility…The Board has…not ruled out future changes to the configuration of this package if developments in Australia and overseas warrant doing so.’

Finally, the speech considered the role of the government’s balance sheet in smoothing out shocks to private sector incomes. Here, the governor spoke in favour of both the JobSeeker and JobKeeper programs and of government spending on infrastructure and public health. He conceded that using ‘the public balance sheet in this way inevitably requires government borrowing against future income…For a country that has got used to low budget deficits and low levels of public debt, this is quite a change. But it is a change that is entirely manageable and affordable and it's the right thing to do in the national interest.‘ In support of this position, Lowe cited the relatively low level of Australian government debt compared to most of our advanced economy peers and the fact that Canberra ‘can borrow at the lowest rates since Federation.’

Why it matters:

There were four key messages in this week’s speech.

First, the RBA remains reluctant to contemplate any more radical monetary policy innovations than the ones it has already introduced. Governor Lowe restated his longstanding aversion to a policy of negative interest rates and also argued that current conditions were not supportive of any intervention to lower the Australian dollar (despite noting in the Q&A session that he would like to see the AUD weaker than its current level). He also ruled out the case for monetary financing and helicopter money, including the more orthodox versions proposed by ‘mainstream economists,’ stressing instead that Australia had ample fiscal space to deploy macroeconomic stimulus.

Second, the RBA is however apparently prepared to contemplate tweaking the parameters of the March monetary package, including perhaps by lowering the cash rate to just 10bp (implying that 0.25 per cent may not be the effective lower bound (ELB) after all?) and / or by ramping up bond purchases. But we are not there yet.

Third, the central bank is very comfortable with the government’s efforts to provide fiscal support for the economy. It sees no significant debt constraint on stimulus, pointing to a debt burden that is relatively modest by international standards, strong demand for Australian government debt and the ability to borrow for five years at just 0.4 per cent and for ten years at just 0.9 per cent.

Fourth, while the RBA acknowledges that at some point in the future ‘attention will rightly return to addressing the ratio of public debt to GDP’, it thinks that ‘the best way to do this will be through economic growth.’ That in turn means a focus on measures designed to lift the economy’s growth potential – another recurring message from the governor.

A final thought. The governor’s fairly conservative views on monetary policy options should come as no surprise – central bankers are not typically selected for their radicalism. Yet central bank conservatism is not what it was. Consider the quite dramatic changes to monetary policy that have already occurred in just a short space of time, with a rock bottom cash rate (although the speech and this month’s minutes did suggest that we may not be quite at the ELB after all), government bond purchases and the adoption of yield curve control. Other central banks including the US Fed and the Bank of England have also been experimenting with what are actually quite radical policy ideas. The evolution of monetary policy is currently taking place on fast forward, meaning that it would be foolish to completely rule out further big changes in the future, despite the consistency of current messaging.

What happened:

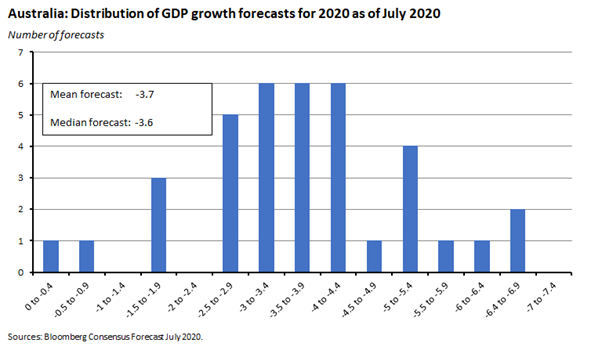

Bloomberg’s latest survey of private sector economists showed the consensus (median) forecast for GDP growth this year rising to -3.6 per cent from a forecast of -4.0 per cent in June. The consensus forecast for growth in 2021 also edged up slightly, rising from a projected 3.3 per cent growth in June’s survey to 3.4 per cent in July.

Why it matters:

Private sector forecasters have trimmed their expectations about the likely depth of the recession this year for a second consecutive month, in a sign that the blow to the economy from COVID-19 – while still severe – has not turned out to be quite as brutal as originally feared. But while the range of growth forecasts for 2020 has narrowed slightly relative to the responses collated in June’s survey, it still spans a fairly broad distribution of outcomes, reflecting the persistent level of uncertainty as to how the second half of this year will unfold.

What happened:

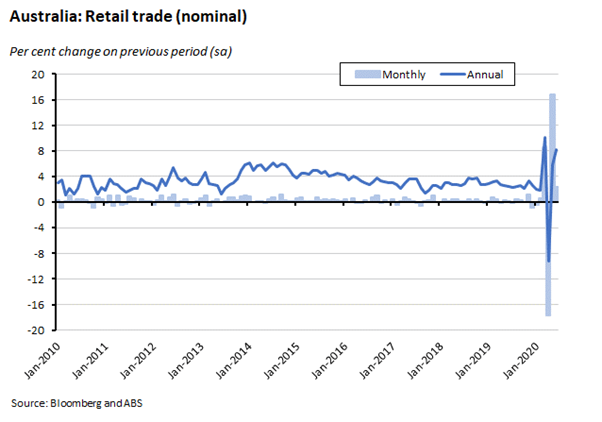

The ABS said that preliminary retail turnover for June rose by 2.4 per cent over the month (seasonally adjusted) to be up 8.2 per cent over the year. These numbers are based on early data provided by businesses that make-up approximately 80 per cent of total retail turnover.

The Bureau pointed to large monthly increases in turnover in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services (up more than 20 per cent for a second consecutive month), and in clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (up around 19 per cent), although turnover in both sectors remains down on the same month in 2019. Meanwhile, the previously rapid pace of increase in food retailing appears to have eased, up 0.9 per cent in June following a 7.2 per cent month-on-month rise in May, although here turnover remains high in annual terms.

Why it matters:

Unsurprisingly, the retail numbers continue to be influenced heavily by COVID-19, even if the outsized monthly shifts of April and May are now behind us. For example, the ABS noted that its analysis of supermarket scanner data is consistent with a continuation of the trend of more food being prepared and consumed at home due to social distancing. The Bureau also noted that there was evidence of renewed stockpiling of goods such as toilet paper, flour, rice and pasta at the end of June, particularly in Victoria.

What happened:

The RBA published the minutes from its 7 July Board meeting, at which the central bank had decided to leave its policy settings unchanged. The minutes note that members discussed ‘how the elements of the Bank's March policy package could have been configured differently, noting that there has been variation across countries in the design of these measures. It would have been possible, for example, to set lower, but still positive, interest rate targets and to have purchased a quantity of government bonds above that necessary to achieve the bond yield target. Members also recognised that there was variation across countries in the design of term funding facilities and the range of collateral accepted in open market operations. After reviewing experience both overseas and in Australia, members agreed that there was no need to adjust the package of measures in Australia in the current environment.’

Why it matters:

The release of the minutes this month was overshadowed by Governor Lowe’s speech on the same day (see above) which as well as setting out the RBA’s current views on the economy and the role of public sector balance sheets also spent some time on the Board’s discussion of monetary policy options.

. . . and what I’ve been following in the global economy

What happened:

EU leaders agreed this week to set up a Euro750 billion Pandemic Recovery Fund, based around a Euro390 billion program of grants targeted at weakened member states with the balance made up of loans. Leaders also agreed on a new seven-year budget for the EU of more than Euro1 Trillion.

Why it matters:

Tuesday’s deal is potentially a landmark moment for the EU. It marks the first time that EU members have agreed to the issuance of joint debt at a significant scale and as such represents a significant step forwards in the EU’s painfully slow march towards fiscal integration. It may not turn out to be the EU’s ‘Hamiltonian Moment’ – sceptics can point to the watering down of the grant element from Brussels’ original bid for a Euro500 billion pool, the presence of conditionality and the absence of cross-default clauses as indicating that some EU members continue to be distinctly ambivalent about the idea of a fiscal union – but there’s no doubt that it is a symbolically important one.

What happened while we were away...

What happened:

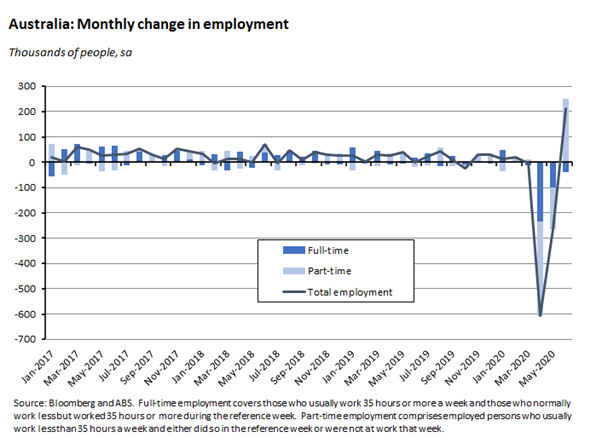

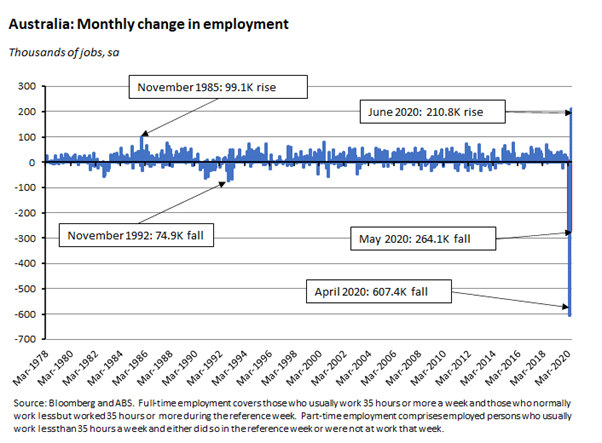

The ABS published the June labour force results. The number of employed persons rose by 210,800 with the increase driven by a rise in part-time employment of 249,000. In contrast, full-time employment decreased by 38,100 persons.

The number of unemployed increased by 69,300 persons in June, taking the unemployment rate up from 7.1 per cent in May to 7.4 per cent last month. The underemployment rate moved in the opposite direction, falling 1.4 percentage points to 11.7 per cent and as a result the underutilisation rate also declined, dropping one percentage point to 19.1 per cent.

The rise in employment and decline in underemployment were also reflected in a four per cent increase in the number of hours worked in June, as the average hours worked per employed person rose to around 31.1 hours per week, up from about 30.4 hours in May.

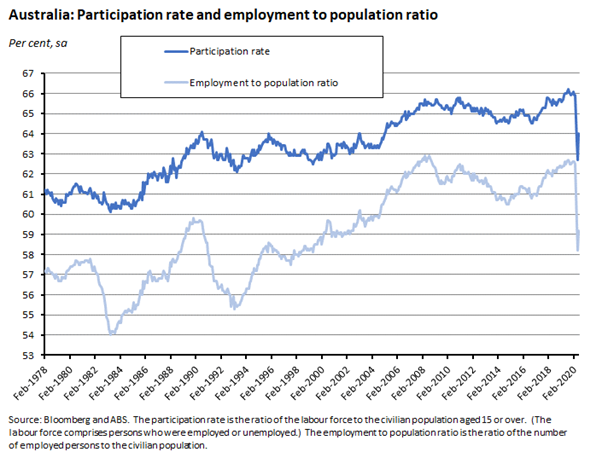

Any positive impact of last month’s rise in employment on the headline unemployment rate was more than offset by an increase in the participation rate, which rose by 1.3 percentage points to 64 per cent. At the same time, the employment to population ratio also increased by about a percentage point to 59.2 per cent.

All states and the ACT enjoyed increases in employment in June, although the Northern Territory suffered a small decrease. The largest increases in employment were recorded in New South Wales (up 80,800 people), Queensland (up 52,900 people) and Victoria (up 29,500 people). Unemployment rates increased everywhere last month except for Queensland (down 0.1 percentage points) and the Northern Territory (down 1.8 percentage points), with the biggest increases in the jobless rate taking place in South Australia (up 0.9 percentage points to 8.8 per cent) and the ACT (up one percentage point to 5.1 per cent).

Why it matters:

The headline growth in employment in June delivered a bit of a pleasant surprise, with the actual rise of almost 211,000 significantly outperforming consensus expectations for a 100,000 bounce back. Unfortunately, the details of were somewhat less encouraging: all the increase came in the form of a rise in part-time employment with full-time employment falling again last month.

Moreover, while June’s increase in employment easily exceeded the previous record monthly gain in the current series (an increase of more than 99,000 in November 1985), that rise has to be seen in the context of total jobs lost of more than 871,000 in the previous two months. In other words, June’s outsized gain was only large enough to restore about a quarter of the cumulative jobs lost in April and May.

Another feature of labour market data in the COVID-19 era has been the exit of workers from the workforce, with the labour force shrinking by more than 481,000 in April and by a further 183,000 in May. It has been this exit process that has kept the unemployment rate in single digits as a large share of those losing employment have exited the labour market rather than joining the ranks of the unemployed. June brought a partial unwinding of this process, with the labour force (the sum of the employed and the unemployed) expanding by more than 280,000 last month as the participation rate increased. As noted above, it was that increase in participation that sits behind the rise in the June unemployment rate despite the sharp jump in employment. Further, that rise in participation was only enough to partially unwind the exit of workers over the previous two months: the labour force is still more than 384,000 workers smaller than it was in March.

At 7.4 per cent, the official unemployment rate was slightly above consensus forecasts for a 7.3 per cent print. That’s the highest rate of unemployment recorded since 1998. Moreover, it’s an underestimate of the true amount of slack in the labour market. For example, if those workers that have left the labour force since March were included in the count of unemployed, then the ‘true’ number of unemployed would be around 1,377,000 and the ‘true’ unemployment rate about ten per cent. Add in the share of those workers supported by the JobKeeper program who would otherwise be out of work, and the unemployment rate would be higher still. This week, the Treasurer said that he thought the effective unemployment rate was around 11.3 per cent – far above the official ABS estimate.

Finally, with the impact of the current Victorian lockdown likely to be felt in the July and August labour market reports, and with some sign of a slowdown in the rate of labour market repair in the latest payroll data (see next story), it’s clear that the job market remains in a precarious position, reinforcing the case for the extension of the government’s fiscal support efforts delivered this week.

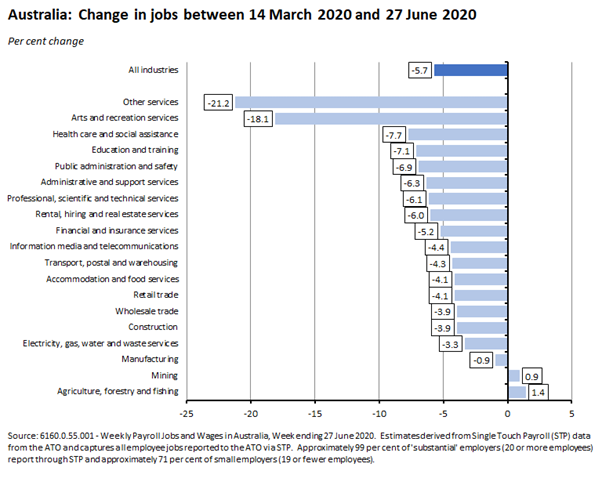

What happened:

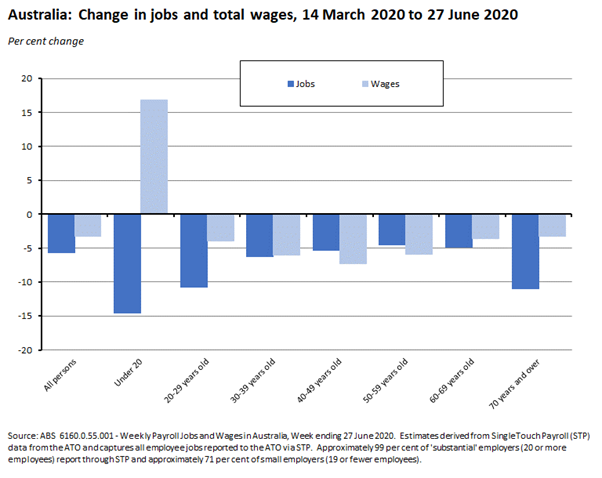

According to the latest ABS weekly data on jobs and payrolls, between the week ending 14 March 2020 (the week Australia recorded its 100th confirmed COVID-19 case) and the week ending 27 June 2020, the number of payroll jobs decreased by 5.7 per cent while total wages paid decreased by 3.2 per cent. Over the most recent period covered by the payroll data – between the weeks ending 20 and 27 June – payroll jobs fell by one per cent and wages fell 0.7 per cent.

By industry, the largest changes over the period since 14 March include a more than 21 per cent fall in jobs in accommodation and food services and a more than 18 per cent fall in arts and recreation services. Mining and agriculture are the only sectors to have added jobs over this period. In terms of total wages paid, the largest declines are in the accommodation and food services sector (down 17.9 per cent) and mining (down by 16.7 per cent).

By state, the largest falls in payroll jobs were in Victoria (down 6.6 per cent) and the ACT (down 6.3 per cent) while the biggest drops in total wages were suffered by Western Australia (down 5.4 per cent) and New South Wales (down 4.1 per cent).

By age distribution, since the week ending 14 March 2020 the largest changes in jobs numbers have been in those worked by people aged 70 and over (decreased by 8.7 per cent) and those worked by people aged 20-29 (decreased by 8.6 per cent). Notably, total wages paid to people aged under 20 have increased by 11.6 per cent over this period, while total payments to all other age categories have fallen.

Finally, by sex, payroll jobs worked by females have fallen six per cent since the week ending 14 March while those worked by males have declined 5.4 per cent. Wages paid to males are down 5.2 per cent and payments to females down 0.2 per cent.

Why it matters:

Last week’s payroll numbers contained a mix of good and bad news.

On the upside, the scale of the total decline in jobs since March has continued to be wound back: the previous payroll release had reported a 6.4 per cent fall in jobs from the week ending 14 March, versus the latest estimate of a 5.7 per cent decline. According to the ABS, since the low in mid-April, total payroll jobs have increased by 3.3 per cent, and as a result, by the end of last month, around 35 per cent of payroll jobs initially lost had been recovered.

On the downside, that means that 65 per cent of jobs are yet to be restored and the experience of previous recessions suggests that the pace of job recovery is likely to slow over time. Potentially worrying in that regard is that the most recent weekly numbers showed payroll jobs falling, suggesting there’s a risk that the initial recovery in employment may be running out of steam. Granted, the payroll data is quite volatile and is subject to large revisions, so it’s sensible not to read too much into one weekly result. Still, it does sound a warning bell.

What happened:

The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment fell (pdf) 6.1 per cent to 87.9 in July, from 93.7 in June.

The monthly index was pulled down by souring sentiment on the economy as the ‘economy, next 12 months’ sub-index recorded the biggest decline of the various component indices, slumping 14 per cent in July to be 25 per cent below pre-COVID levels. That drop was not as steep as the 40 per cent plunge in sentiment recorded during the ‘first wave’ of the virus in March-April but it was still substantial. There was also a sizeable 10.3 per cent fall in the ‘economy, next five years’ sub-index, indicating that households are now less comfortable about expecting a bounce back in the medium term.

Why it matters:

Westpac economists noted that July’s drop in confidence reversed all of June’s increase, taking sentiment back to the levels seen in May (but still 16 per cent above April’s extreme low of 75) in a pattern that is broadly consistent with the weekly ANZ-Roy Morgan numbers discussed above.

The July survey covered the week in which the lock down was announced for Melbourne but had closed before news of the spike in cases in Sydney, so it captures the hit to sentiment from events in Victoria but not in NSW. That’s reflected in the state by state results, with Victoria’s sentiment index slumping by more than ten per cent this month while sentiment across the rest of Australia was down by less than five per cent on a combined basis. That does suggest there is some risk of a further hit to sentiment next month from developments in NSW.

What happened:

The NAB monthly Business Survey for June showed business conditions rising 17 points in the month to minus seven index points, with the improvement led by increases in mining and retail, but with the reported recovery broad-based across industries and states. Business confidence rose by 21 points to an index level of one, returning that index to positive territory for the first time since January.

Why it matters:

The business readings for June delivered a second consecutive bounce in reported conditions and confidence and as such were consistent with the economic story that applied before the news of the rise in COVID cases in Victoria – that is, a story of a recovery in confidence and conditions as lockdowns were eased and the authorities appeared to be on top of the public health challenge. It’s also consistent with the evidence presented by global PMIs of a broader, worldwide pick up in business activity. All that said, in level terms, the indicator of business conditions remained very weak.

The reaction of consumer sentiment in July (see previous story) suggests that there will be some pullback in next month’s results: the June business survey was conducted just before the reintroduction of lockdowns in Victoria.

What happened:

The RBA Board met on 7 July. At the meeting, the Board ‘decided to maintain the current policy settings, including the targets for the cash rate and the yield on 3-year Australian Government bonds of 25 basis points.’

The accompanying statement noted that the ‘Australian economy is going through a very difficult period and is experiencing the biggest contraction since the 1930s’ while continuing on to acknowledge that ‘Conditions have, however, stabilised recently and the downturn has been less severe than earlier expected.’ Even so, the RBA remains cautious: ‘Notwithstanding the signs of a gradual improvement, the nature and speed of the economic recovery remains highly uncertain.’ As a result, it judges that continued fiscal and monetary support for the economy ‘will be required for some time.’

Why it matters:

The RBA remained consistent in its messaging here, with little change in its views from the previous monthly meeting. The central bank did note that the COVID downturn to date has been less severe than initially feared but against that it also emphasised that the economy still faces huge uncertainties. It therefore continues to point out that macro policies will need to offer sustained economic support for some time yet. The return to lockdown in Victoria will only have reinforced that sense of caution.

What happened:

ANZ Job Ads rose by a record 42 per cent over the month in June, with the strongest growth taking place in the hospitality and tourism sector.

Why it matters:

Last month’s jump in ads comfortably outpaced the previous record monthly rise of 17.7 per cent set back in February 2010. But while the rapid rate of increase reported here was certainly positive news, that still left the level of ads a substantial 41 per cent below their February 2020 level, before the pandemic began to unravel the Australian labour market.

What happened:

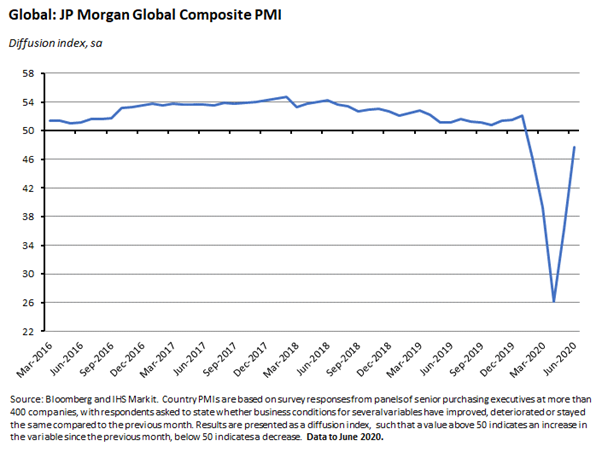

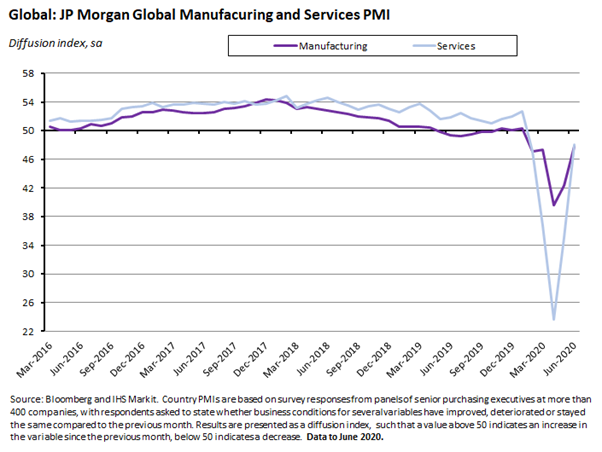

The JP Morgan Global Composite PMI rose (pdf) to 47.7 in June, reaching a five-month high and climbing by a record 11.4 points from May.

The index remained in negative territory in June, indicating that global output contracted for a fifth successive month, although the rate of that decline has eased sharply. Both the Manufacturing and Services Indices rose to the greatest extents in their respective series histories, breaking the records that had just been set in May. The global service sector saw output fall much faster than manufacturing during the height of the lockdowns, largely reflecting the impact from social distancing policies, and has likewise showed signs of a stronger rebound as those same restrictions have been relaxed.

Composite output PMI data are calculated for 14 economies. Of these, three (China, Australia and France) registered outright expansions in June, up from only one (China) in May. All the remaining 11 countries enjoyed a sharp diminution in the rate of contraction compared to May, in many cases to either the steepest or second-steepest extent ever.

Why it matters:

The record jump in June followed on from a prior record increase in May, as economies across the globe began to re-open from their lockdowns. Despite those two big rises, however, a reading of 47.7 means that the PMI is still below the no-change 50 level and therefore means that the world economy has now suffered a fifth successive monthly deterioration of output across the combined manufacturing and service sectors.

Analysts at survey provider IHS Markit reckon that, when compared to official data, the strong improvement in the survey index in June is ‘indicative of a return to annual GDP growth for the global economy for the first time since January.’ That’s because although a reading of 50 means that the number of companies reporting higher output and lower output are in balance, their comparisons to official data suggest that an index reading of 46.7 is the cut-off between global GDP rising or falling on an annual basis, meaning that June’s reading has moved us to the ‘right’ side of this other dividing line. Their model of the relationship between the annual growth rate of global GDP and the PMI suggests that the annual rate of decline in world growth likely peaked at approximately minus 12 per cent back in April this year, reflecting worldwide COVID-19 related lockdowns, and that the subsequent relaxation of virus restrictions has helped drive a 0.6 per cent annual rate of growth in June.

Does the big rebound in PMIs suggest a V-shaped global recovery? There are limitations in mapping PMI movements onto GDP growth. In part, that’s because the PMI survey asks companies to report on monthly changes in production trends, and therefore tends to change direction earlier than annual changes in GDP. As an example, IHS Markit notes that after the global financial crisis, the PMI signalled a return of annual GDP growth in June 2009, but it wasn't until the fourth quarter of 2009 that GDP rose above levels of the previous year.

More importantly, however, the CVC is quite different from previous global recessions: the record gains in both manufacturing and services in June are the consequence of shifting away from the unprecedented enforced business closures and more general lockdowns. Those same lockdowns have also generated some pent-up demand for at least some goods and services that is now benefitting at least some firms. And then there’s the contribution of massive emergency stimulus measures. All of which means that the durability of this kind of recovery past the initial bounce back is particularly hard to gauge even before considerations of renewed public health challenges.

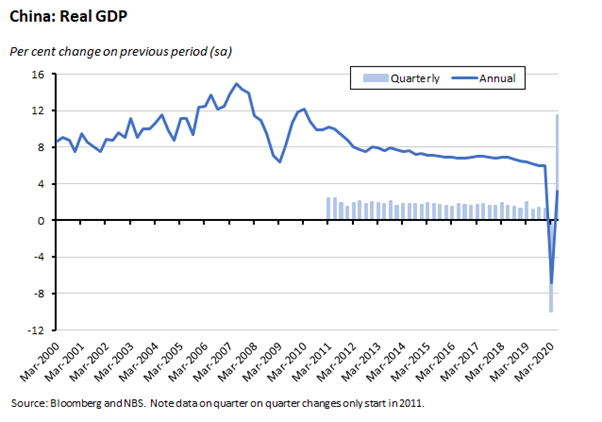

What happened:

China’s GDP rose 11.5 per cent over the quarter in Q2:2020 to be up 3.2 per cent over the year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

Why it matters:

China’s 6.8 per cent annual fall in real GDP in Q1 marked the first contraction in output for that country for several decades as well as the onset of the CVC in the global economy. The second quarter results means that the end of lockdowns and some policy stimulus have both been successful in limiting the fall in output to just one quarter and in delivering a decent bounce back, as the Q2 results surprised on the upside, beating market expectations of a 9.6 per cent quarterly rise and a 2.5 per cent annual growth rate.

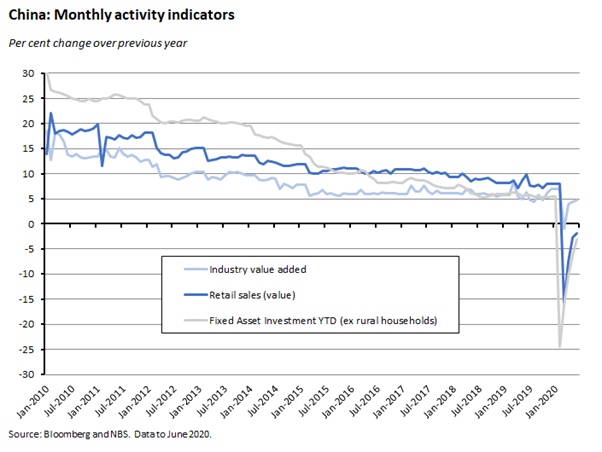

Partial economic indicators for June suggest that the recovery in activity is being led more by industry than it is by consumption, however, with households still cautious: while industrial production rose 4.8 per cent over the year, beating May’s 4.4 per cent annual growth outcome, retail sales fell for a fourth consecutive month, shrinking by 1.8 per cent over the year.

Fixed asset investment for the first half the year was down 3.1 per cent in annual terms, marking an improvement from the 6.3 per cent drop reported for the January-May period. The driver of the improvement was an increase in public investment in the first half, which grew 2.1 per cent over the year after having contracted for the first five months, a consequence of the marked step up in government policy support.

Latest news

Already a member?

Login to view this content